The Skyscraper Museum is devoted to the study of high-rise building, past, present, and future. The Museum explores tall buildings as objects of design, products of technology, sites of construction, investments in real estate, and places of work and residence. This site will look better in a browser that supports web standards, but it is accessible to any browser or Internet device.

HOTELS

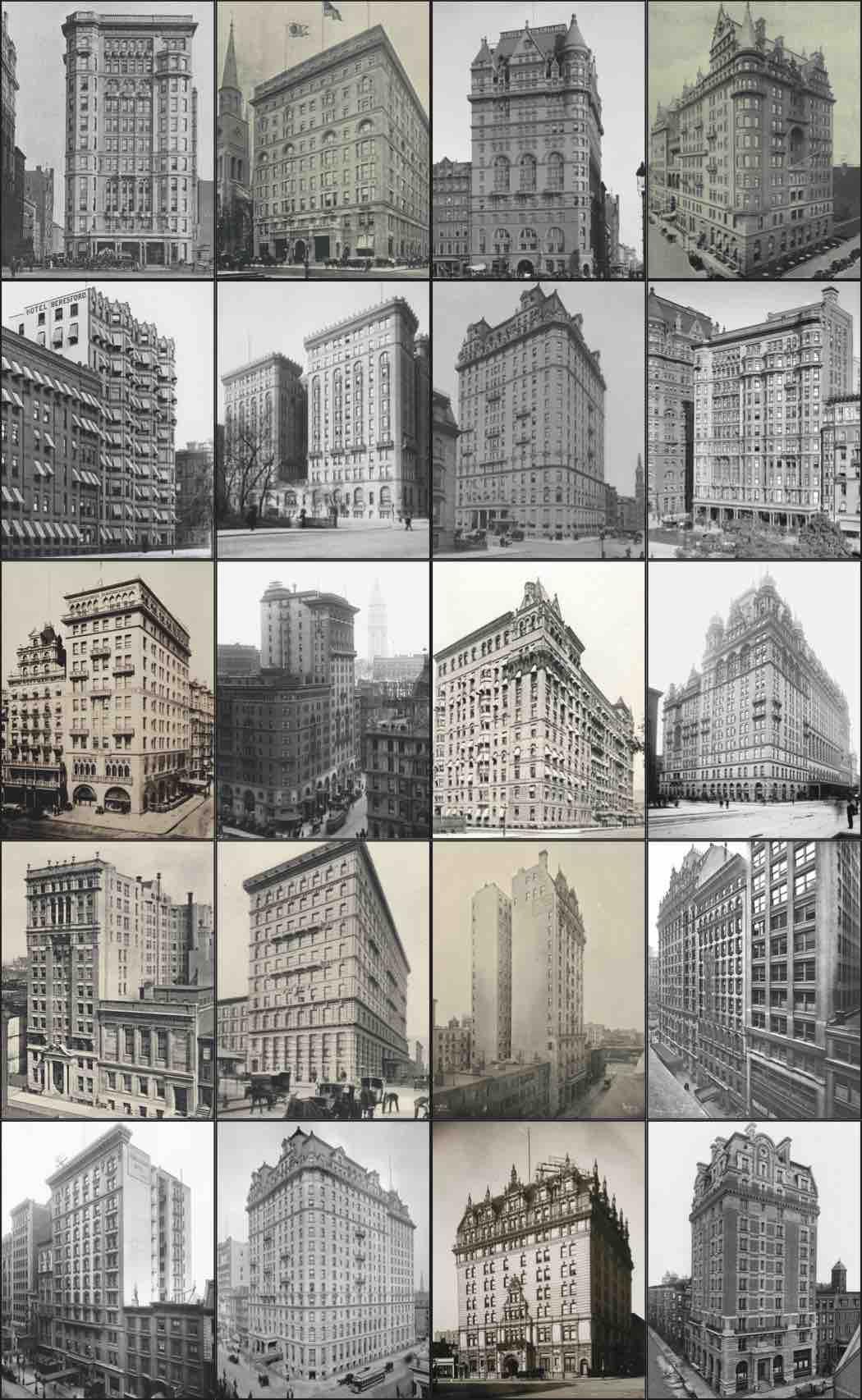

Click here for imgae credits

Hotels, like office buildings, are commercial architecture, designed and erected to earn revenue. Money could be earned through a variety of strategies, including renting large, luxurious rooms at high rates, at a “palace hotel” such as the Waldorf Astoria, or creating cubicles of clean, but tiny rooms to let at 20 cents a night, as at Mills House. Lodging could be rented by tourists for the night, or leased as residences by the week, month, or longer in “family hotels.”

Hotels were an important part of the social fabric of New York since colonial times, but in the 1880s, especially, they began to proliferate. A long article in the New York Times of October 19, 1890 summarized the boom in new construction, noting the profitability of the industry: “The hotel men of New-York are a contented lot just now. There never was a time when their business was so uniformly good as at present.”

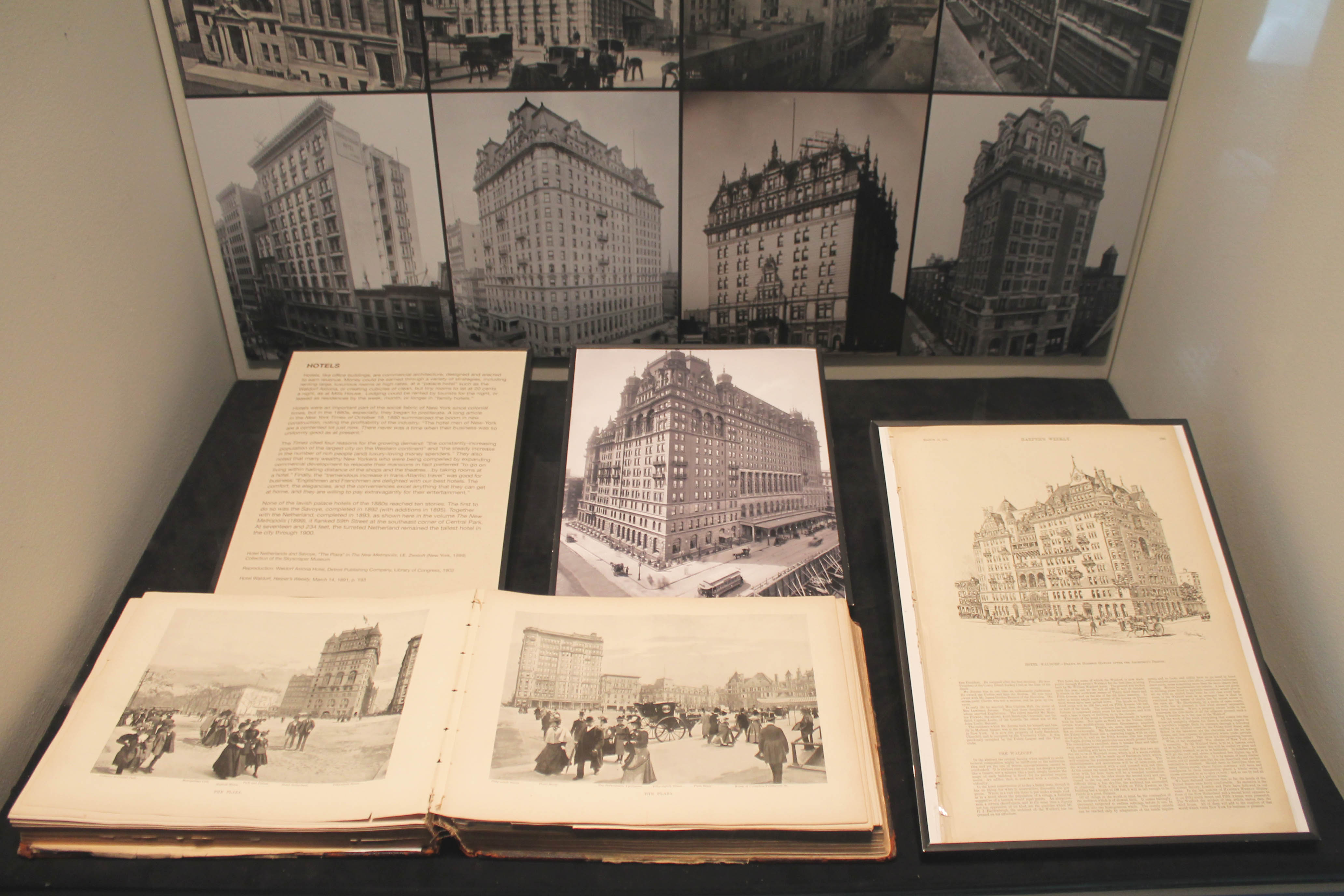

Left: Hotel Netherlands and Savoye, “The Plaza” in The

New

Metropolis, I.E. Zeisloft (New York, 1899) Collection of the Skyscraper Museum.

Left: Hotel Netherlands and Savoye, “The Plaza” in The

New

Metropolis, I.E. Zeisloft (New York, 1899) Collection of the Skyscraper Museum.

Middle: Reproduction: Waldorf Astoria Hotel, Detroit Publishing Company, Library of Congress, 1902

Right: Hotel Waldorf, Harper’s

Weekly, March 14, 1891, p. 193

The Times cited four reasons for the growing demand: “the constantly-increasing population of the largest city on the Western continent” and “the steady increase in the number of rich people (and) luxury-loving money spenders.” They also noted that many wealthy New Yorkers who were being compelled by expanding commercial development to relocate their mansions in fact preferred “to go on living within hailing distance of the shops and the theatres…by taking rooms at a hotel.” Finally, the “tremendous increase in trans-Atlantic travel” was good for business: “Englishmen and Frenchmen are delighted with our best hotels. The comfort, the elegancies, and the conveniences excel anything that they can get at home, and they are willing to pay extravagantly for their entertainment.”

None of the lavish palace hotels of the 1880s reached ten stories. The first to do so was the Savoye, completed in 1892 (with additions in 1895). Together with the Netherland, completed in 1893, as shown here in the volume The New Metropolis (1899), it flanked 59th Street at the southeast corner of Central Park. At seventeen and 234 feet, the turreted Netherland remained the tallest hotel in the city through 1900.

The Hotel Majestic

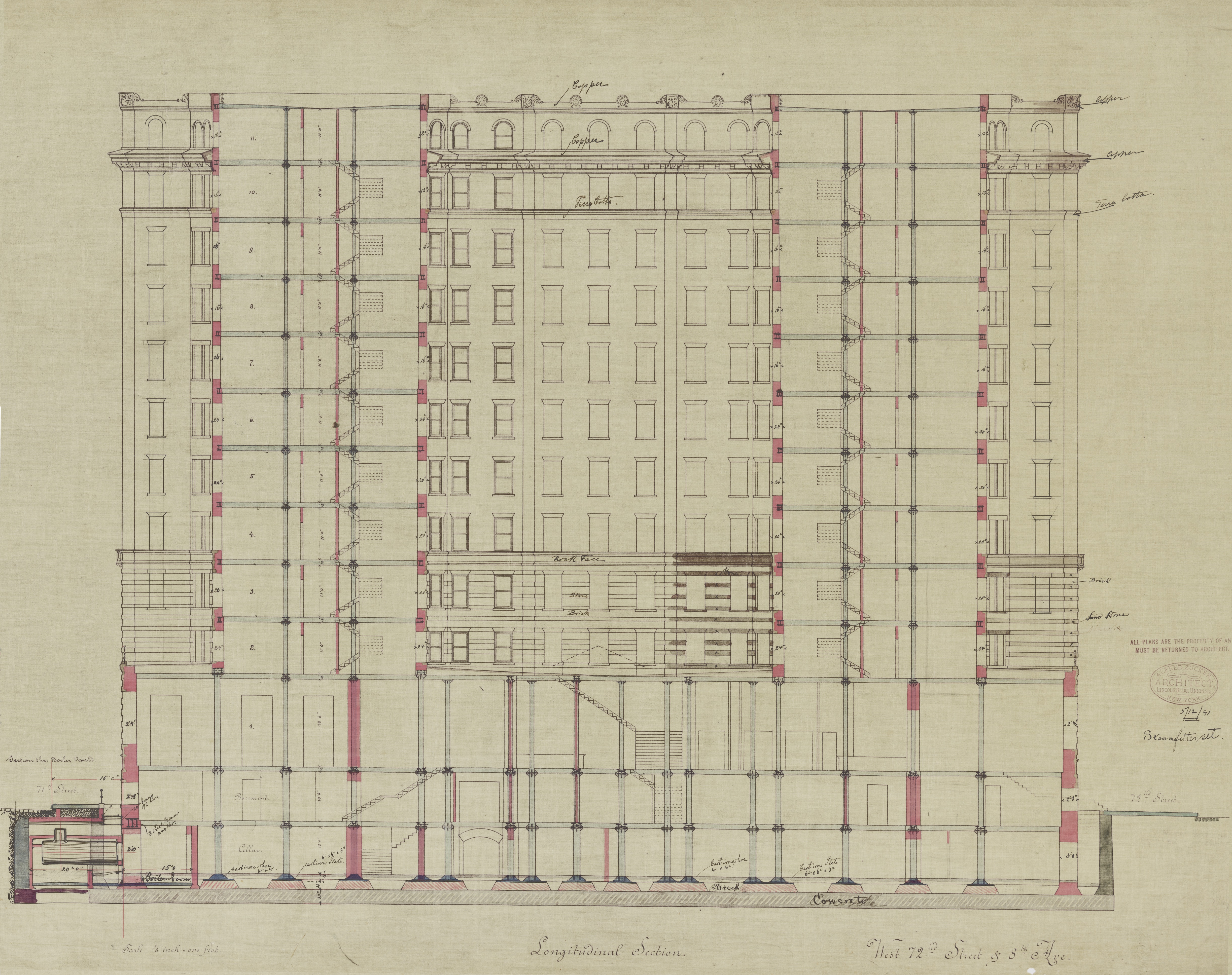

Reproductions from drawings in the collection of the Alexander Architectural Archives, University of Texas Libraries

Reproductions from drawings in the collection of the Alexander Architectural Archives, University of Texas Libraries

Left: Perspective Rendering; Middle: Elevation on 72nd Street;

Right: Longitudinal section

The three reproductions of drawings of the Hotel Majestic by architect Alfred Zucker picture the grand hostelry built in 1894 by German-born developer Jacob Rothschild, originally a millinery dealer. According to the New York Times, Rothschild intended the hotel to be a rival in appearance and appointments to the neighboring Dakota, the apartment house that had pioneered residential architecture on Central Park West and 72nd Street a decade earlier. Together the two buildings appeared to form a monumental gateway to the park.

The Majestic occupied a full block site, with a 202-foot facade on Central Park West and 150 feet on the side streets. Its scale of was enormous: three twelve-story sections were divided by large courtyards, shown here in the structural section, which allowed abundant light and air into the interior rooms. As Architecture and Building described in 1891, the hotel was designed:

Perspective elevation, Alexander Architectural Archives, University of Texas Libraries.

Perspective elevation, Alexander Architectural Archives, University of Texas Libraries.

"To meet a long felt want of a first-class family hotel for the upper west side. The rooms in most cases will be rented in suites of drawing-room, bed-room and bath-room each, or of five rooms, as the case may be. There will be 560 living rooms and 268 bath-rooms. On the main floor, reached by the general entrance on 72d Street, there will be the large hotel lobby, or reception hall, covering four city lots, with the drawing rooms, music rooms, libraries and the large dining room, more than 10,000 square feet of surface.”

The Majestic housed transient guests, but many of its residents were long-term. Many were artists or celebrities, such as actress Sarah Bernhardt, novelist Edna Ferber, and tenor Enrico Caruso. The Majestic was also often referred to as the “Jewish place.” While many residential buildings discriminated against Jewish occupants, the Majestic became the center of organizations such as the Judeans and the Jewish Guild. Grand in its heyday, the hotel was demolished in 1929 to be replaced by the twin-towered, Art Deco Majestic Apartments.