The Skyscraper Museum is devoted to the study of high-rise building, past, present, and future. The Museum explores tall buildings as objects of design, products of technology, sites of construction, investments in real estate, and places of work and residence. This site will look better in a browser that supports web standards, but it is accessible to any browser or Internet device.

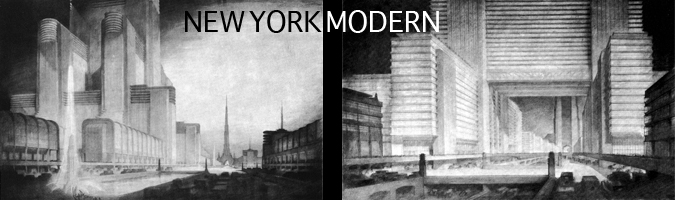

New York Modern

October 24, 2007 through Spring 2008

This is the first exhibition in the FUTURE CITY 20|21 cycle.

CLICK HERE to watch the five-part New York Modern lecture series, presented by Museum Director Carol Willis.

CLICK HERE for a virtual walkthrough of the exhibition.

New York Modern was the first in a cycle of three related exhibitions, spanning a year, entitled FUTURE CITY: 20 | 21 that juxtaposed a retrospective of American visions of the skyscraper city of the future from the early 20th century with an exploration of Chinese cities today, pursuing the parallel conditions of rapid modernization and urbanization. The second exhibition of the cycle focused on Hong Kong and New York, and the third, “China Prophecy,” explored the 21st-century skyscraper city of Shanghai.

"New York 1999," New York World, December 30, 1900.

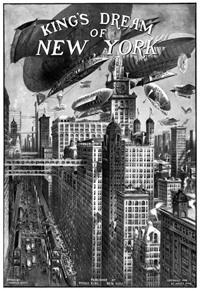

Left: Moses King, "King's Dreams of New York," King's Views of New York, 1911-1912.

Right: William R. Leigh, "Great City of the Future," Cosmopolitan, November 1908.

In the 1920s, though, a new vision of the future swept American culture–a monumental city of towers, multilevel highways, aerial transport, and densely developed commercial districts. Principally the projections of New York architects and planners, this new type of hyper-concentrated urbanism was set forth in dazzling images, not only in professional circles and publications, but in newspapers, books, magazines, art galleries, department stores, and movies.

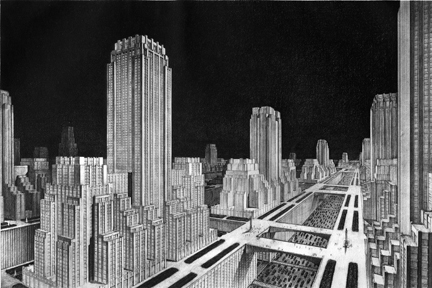

The inspiration and motivation for these prophecies was the city itself–its soaring buildings, teeming streets, and hurtling subways. In 1925, New York passed London to become the world’s largest metropolis. With a population of nearly six million in the city proper, ten million in the region, New York continued to grow in all directions, but especially in Manhattan where the crowding business districts and lightning pace of the skyscraper boom seemed to promise that every block would soon be built anew. Rockefeller Center, the three-block complex of harmonized buildings, roof gardens, pedestrian zones, and richly mixed uses demonstrated a model for an architect-orchestrated urbanism.

Left: Hugh Ferriss, "Skyscraper Hangar in a Metropolis," 1930. Right: Hugh Ferriss,

"Aerial View of an Imaginary City," 1930.

New York Modern explored the idea of the skyscraper city of the future in the context of the period’s phenomenal urban expansion, pressing problems of congestion and overbuilding, and new tools for planning and control, such as setback zoning. Three key personalities shaped the debate in architectural circles–Raymond Hood, Harvey Wiley Corbett, and Hugh Ferriss–and offered alternative models for a future city of towers.

Raymond Hood, "Proposal for Manhattan 1950," Montage of Aerial Photograph and Drawing, 1929.

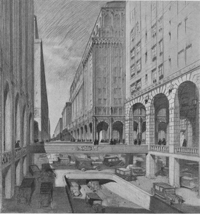

Corbett's concept for separation of vehicular and pedestrian traffic with arcaded sidewalks, RPNY, 1923-24.

Hugh Ferriss, "Looking West from the Business Center," The Metropolis of Tomorrow, 1929.

"100-Story City in the 'Neo-American Style'", Plate CXXIV from Francisco Mujica's 1929/30,

History of the Skyscraper.

"The Proposed Chrystie-Forsyth Parkway," from The Regional Plan of New York and its Environs, 1930.

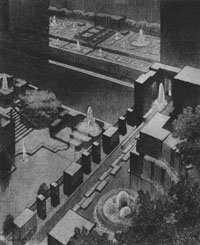

Proposed Roof Gardens, Rockefeller Center.

“From today’s perspective, these ‘past futures’ offer many interesting echoes in 21st century New York,” notes Museum director Carol Willis, who is also the exhibition’s curator. “Concerns about how to deal with traffic congestion, create mixed-use structures, preserve sunlight and nature in the densest of districts, and mitigate the pressure on Manhattan are the same now as they were in the twenties. Clearly, though, the idea that the future New York would be radically rebuilt and barely recognizable, thankfully, did not come to pass.” However, Willis notes, there was a fundamental insight in the visionary urbanism of the 1920s: skyscrapers would define the urban future, and New York, far more than any other place in the world, was the prophecy of the modern city.

* * *