TEN & TALLER examines the history of early high-rises in New York City in the last quarter of the 19th century. The project surveys ALL the buildings ten stories or taller erected in Manhattan in the years 1874 through 1900. To provide multiple perspectives on this group of 253 buildings – in particular, their use, height, and spatial geography – we created three interfaces: a GRID, a MAP; and a TIMELINE.

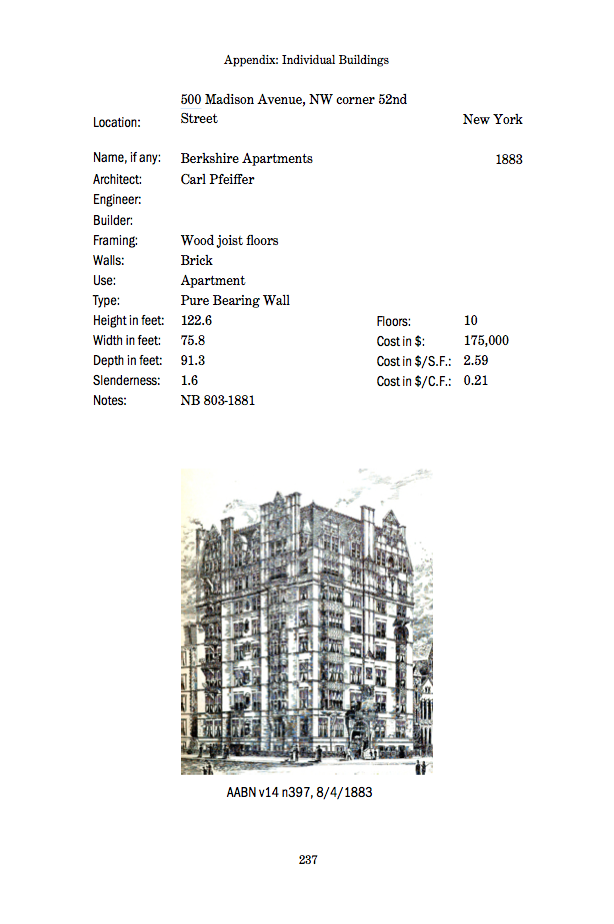

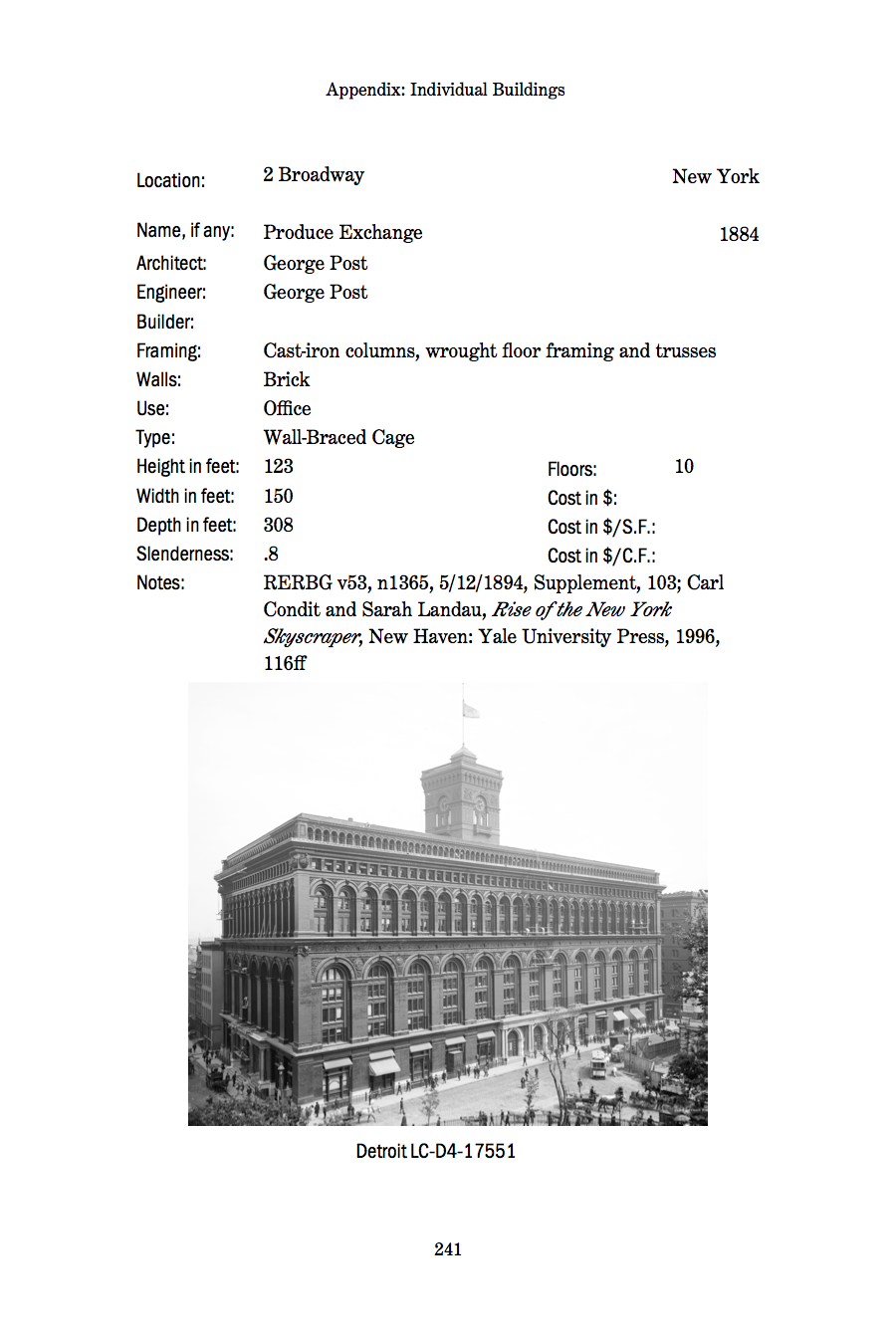

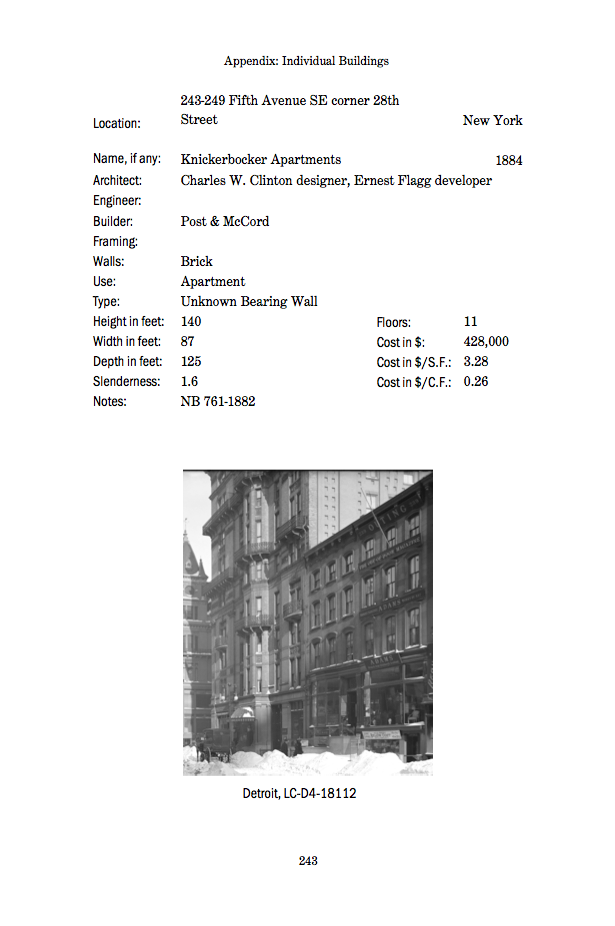

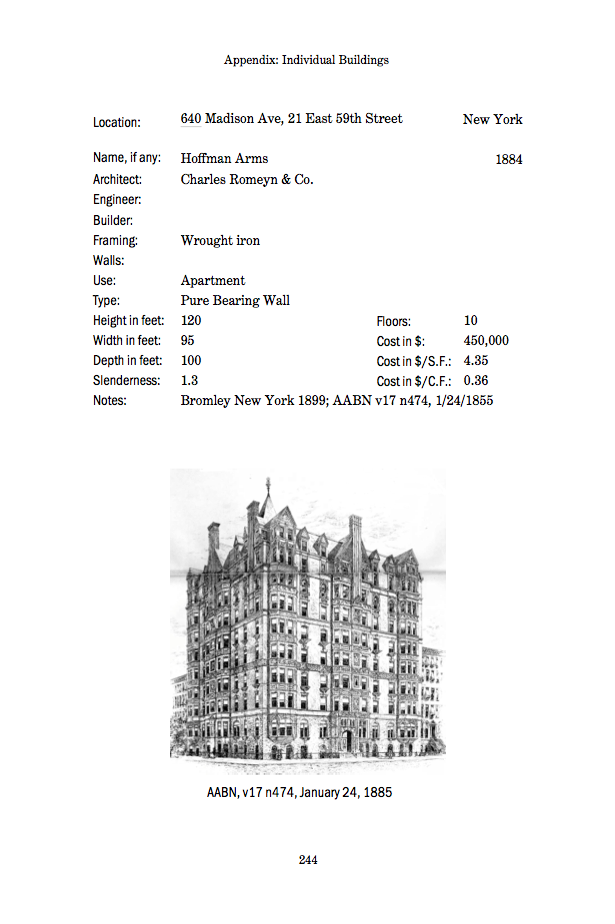

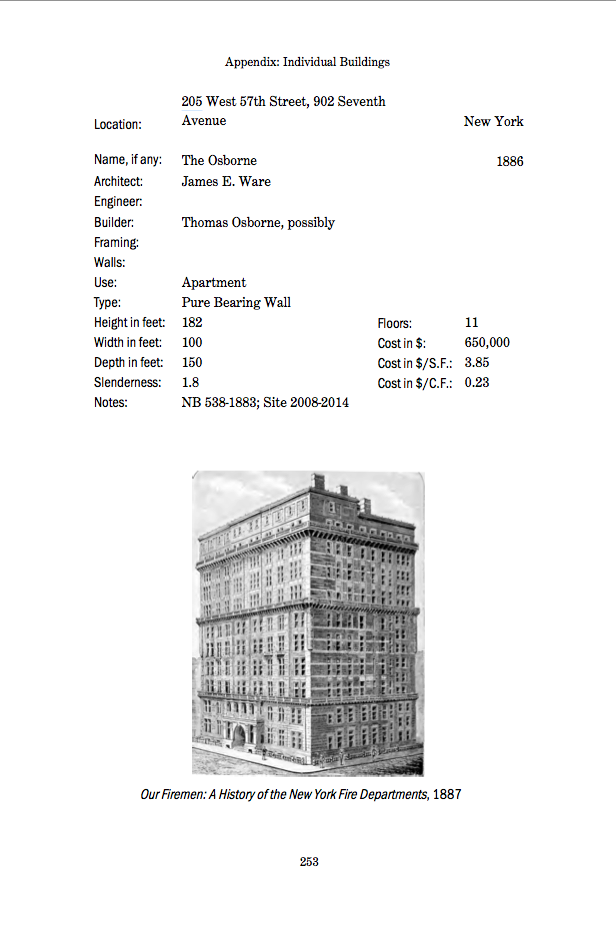

The origin of this project is a comprehensive database created by the structural engineer and historian Donald Friedman. The principal purpose of his survey was to distinguish the structural systems employed in early high-rise construction and to chart the change in technology from masonry to metal-frame construction. In free time over more than a decade, Friedman scoured 19th-century engineering and architecture journals and Department of Building records to compile a complete inventory of all the tallest buildings in New York, as well as in all other American cities, including Chicago. Long described in many textbooks as the “birthplace of the skyscraper,” the “Second City” could boast only 78 buildings taller than ten stories by 1900. Further, Chicago’s fame as the leader in the invention of steel skeleton construction is compared and contested by Friedman’s study of the more multiple and hybrid approaches of structure practiced in New York, where architects and engineers were encouraged by local economics or constrained by codes to use more conservative structural approaches.

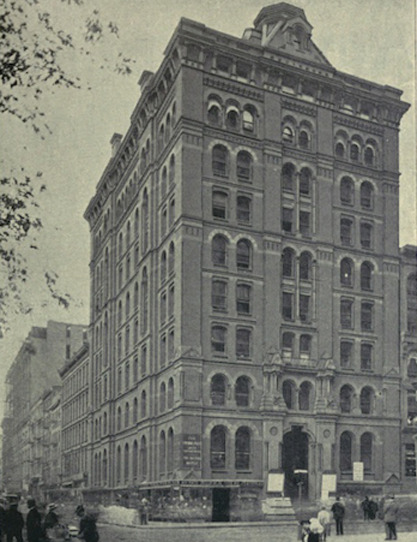

What was the first skyscraper? There’s no simple answer to this oft-asked question, and any response related to height must be understood in terms of context, both of a building’s neighbors and of its historical moment. Ten stories was very tall in the 1870s and 1880s, but less so in 1900. Our GRID begins in 1874 with the Tribune and Western Union Buildings, which at 260 and 230 feet to their tips remained in the top ten of the city’s tallest buildings in 1890 and surpassed all Chicago skyscrapers of that same period. Our TIMELINE charts vertical height, as well as cycles of construction by graphing the height of all 253 buildings of Friedman’s study. It also color codes to distinguish use: offices, residential, lofts, and miscellaneous others.

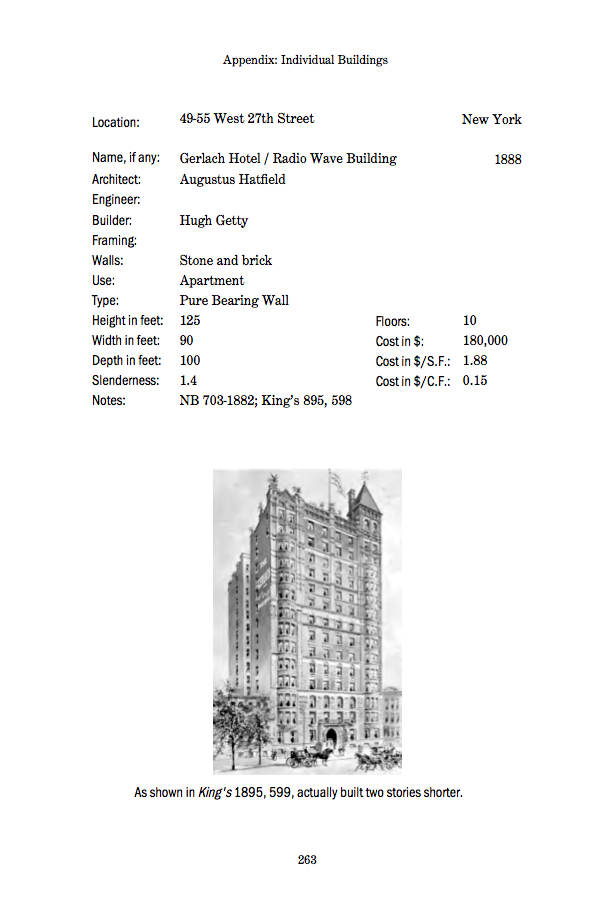

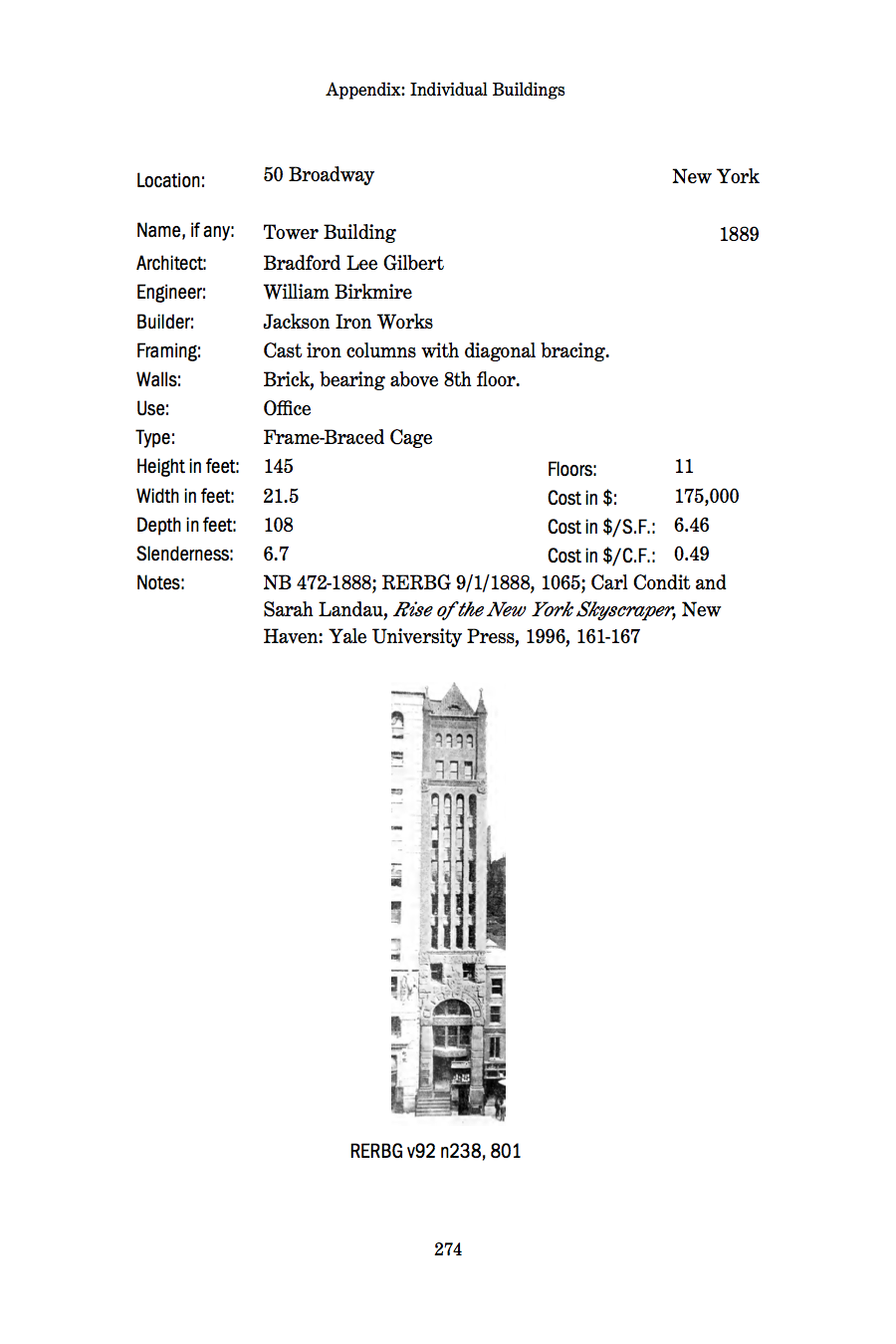

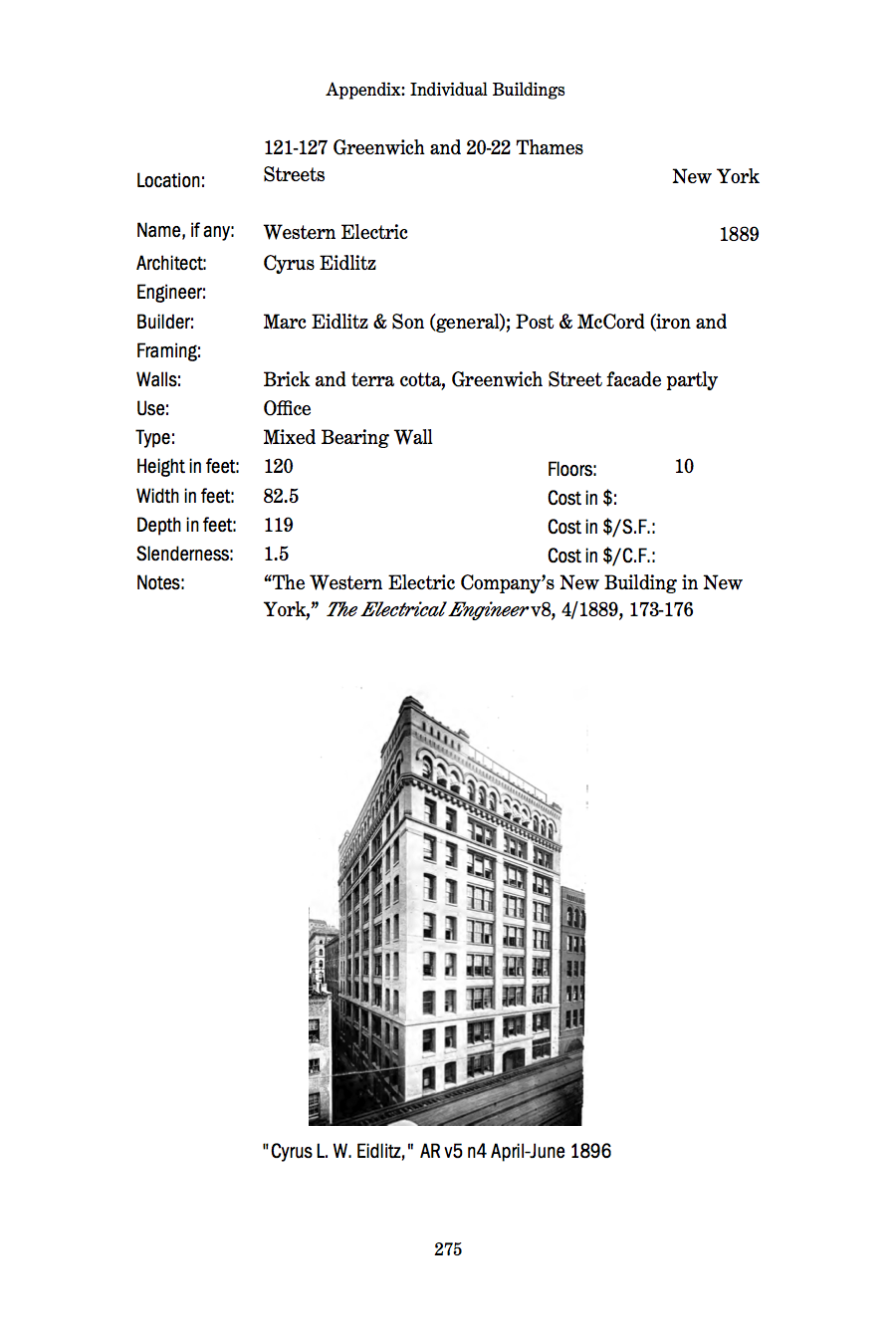

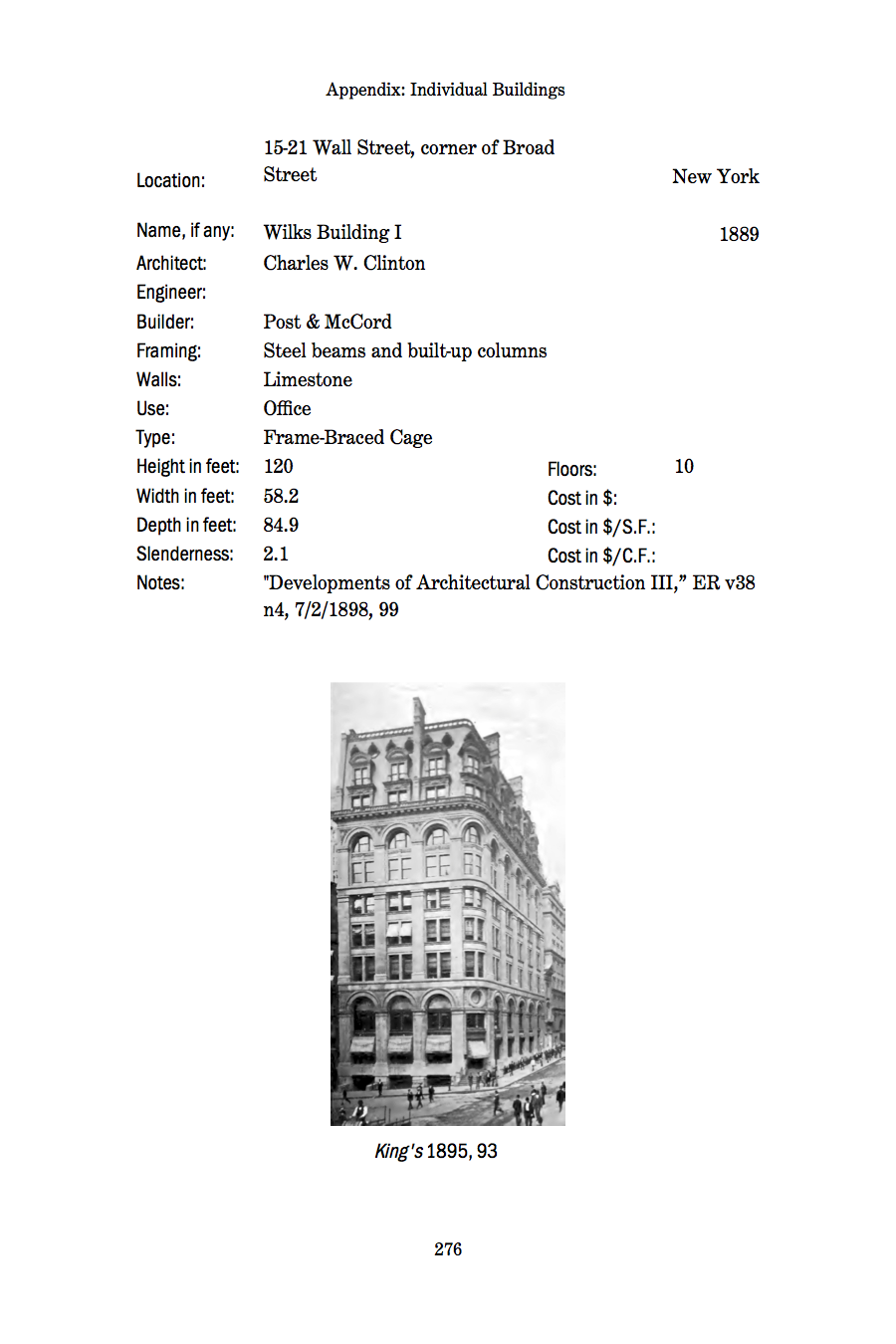

As the GRID reveals, however, the great majority of buildings were blocky structures capped with cornices that emphasize the horizontal. Most people would call these buildings high-rises, not skyscrapers. The idea that a skyscraper is tall and slender and makes a silhouette against the sky is embedded in the term, which was in fact coined in the 1880s.

To identify a building in the grid, click on a tile to open a pop-up window of images and data. Use the three drop-down menus to display or filter existing or demolished* structures and to sort by use and neighborhood. Combined filtering is also possible: e.g. Existing Office Buildings in Lower Manhattan.

*Demolished buildings include those heavily modified. IDs for the image credits are posted here.

Existing / Demolished: Use: Neighborhood: