The Skyscraper Museum is devoted to the study of high-rise building, past, present, and future. The Museum explores tall buildings as objects of design, products of technology, sites of construction, investments in real estate, and places of work and residence. This site will look better in a browser that supports web standards, but it is accessible to any browser or Internet device.

LINOTYPE MACHINE

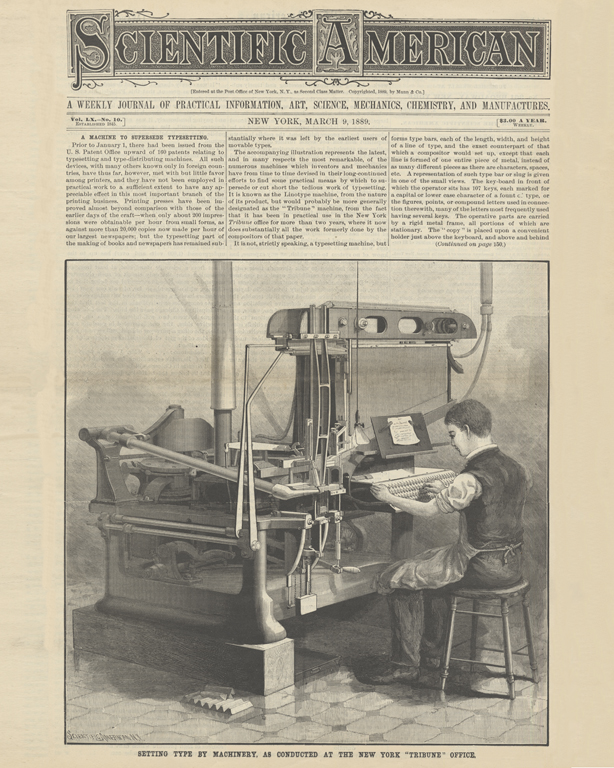

Scientific American, March 9, 1889, cover.

The technology of printing with movable type had changed little from its invention in the 15th century until the 1880s, when several inventors developed a mechanized process of typesetting that composed and cast in lead a full line of type. For most of the history of the printing press, workers would hand place each letter or "sort" into a composing stick to make the words and lines of text, then place those assembled lines into a frame or "forme" to make up the page to be printed. This process required intensive labor and was very time-consuming, compromising the speed of producing a newspaper.

The linotype-the commercial name that came to stand for typesetting machines in general-was invented by Ottmar Mergenthaler, a German immigrant who began his experiments in Baltimore, then moved to New York with the financial support of Whitelaw Reid, editor of the Tribune. The first working model of his invention, as illustrated in the issue of Scientific American at the left, was installed in the Tribune Building by 1887.

The Linotype revolutionized the process of typesetting. With this new machine, an operator could simply type at a keyboard while letter matrices mechanically aligned themselves into lines of text. When the line of type was automatically set and justified, molten lead was infused into the line of letters to cast a metal slug of the full line. These slugs were then composed into columns of type.

Linotype machines were both faster and cheaper than hand typesetting, leading to their widespread adoption. A linotype operator could set type four to eight times faster than a hand compositor, and the learning curve was a short one. An 1891 Popular Science article noted that a first-time user could set over 1,100 ems in an hour-faster than a hand compositor. The decrease in required labor often produced cost savings of fifty percent. These results prompted newspapers such as the New York Tribune, World, Times, Sun, Herald, and Mail and Express to purchase batteries of linotypes for their composing rooms.

By 1911, there were 25,000 linotypes in daily use. Upon opening its new headquarters in 1890, the New York World had one hundred typographs, a competitor's machine, and added an additional 64 Linotype upon its completion of its annex. This advanced and efficient equipment allowed the papers to issue multiple editions per day and to add additional pages.