The Skyscraper Museum is devoted to the study of high-rise building, past, present, and future. The Museum explores tall buildings as objects of design, products of technology, sites of construction, investments in real estate, and places of work and residence. This site will look better in a browser that supports web standards, but it is accessible to any browser or Internet device.

CORE EXHIBITS ON PERMANENT DISPLAY

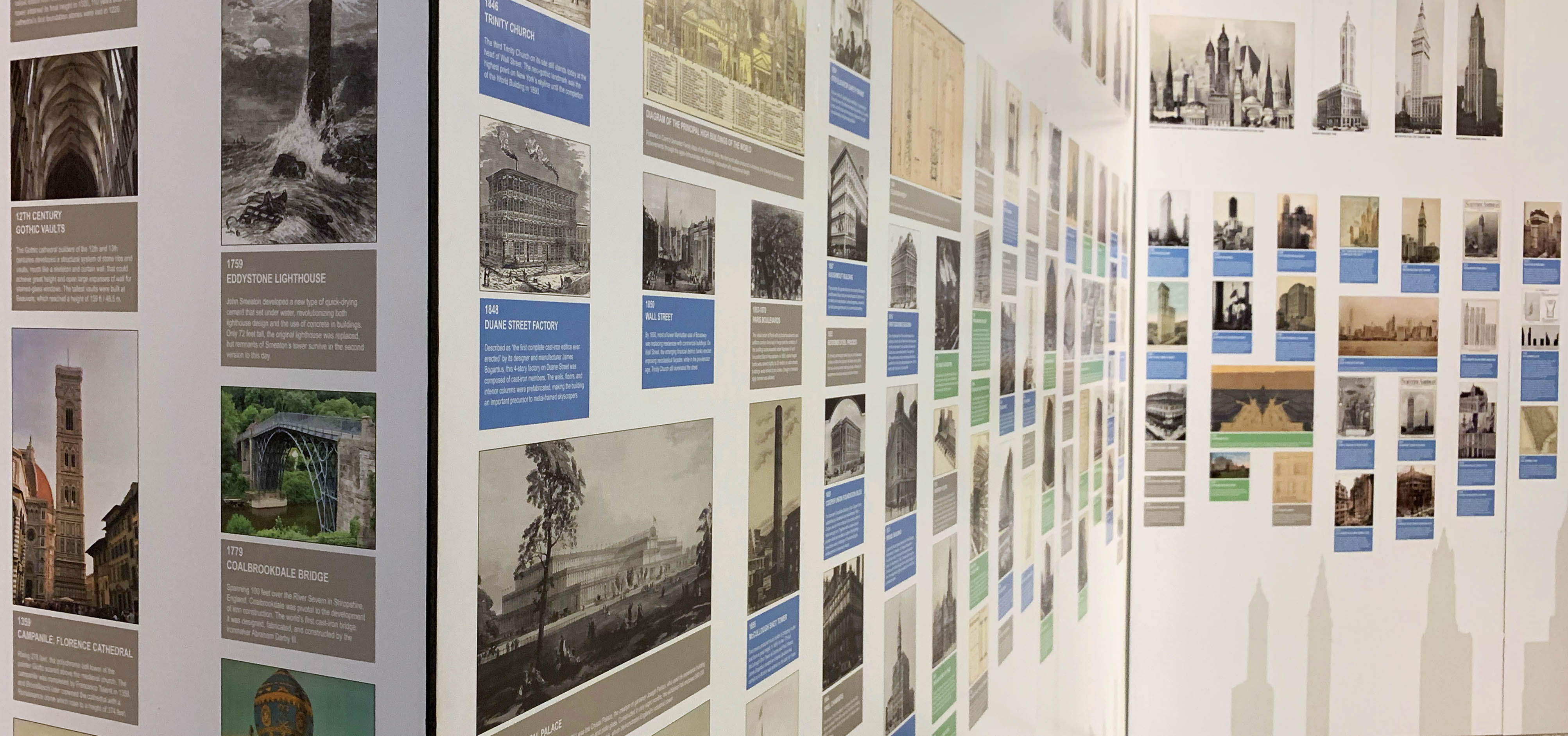

THE HISTORY OF HEIGHT

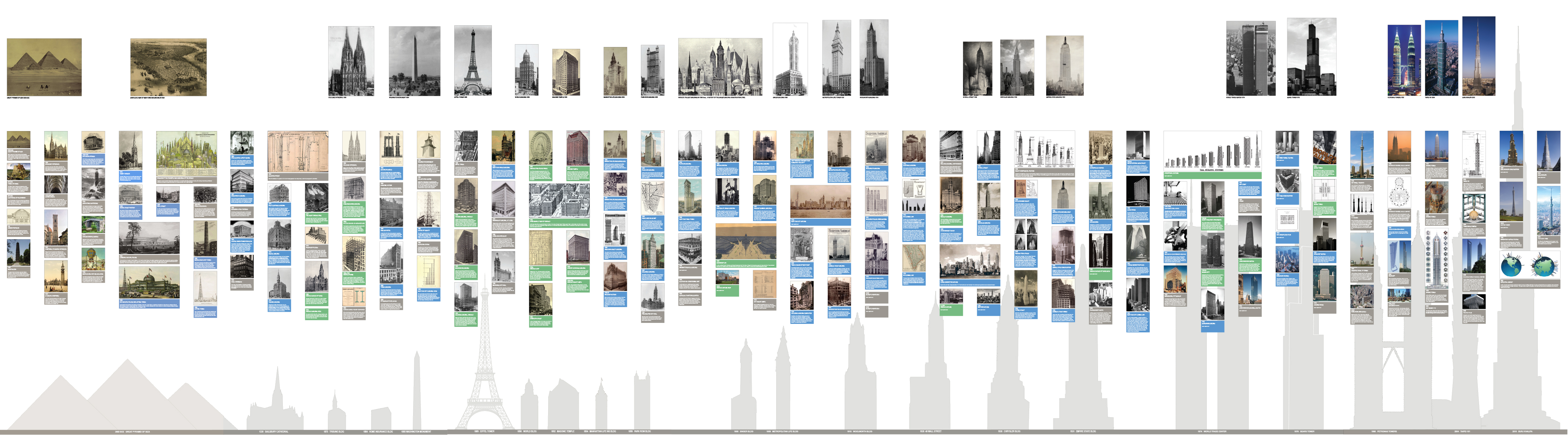

The Skyscraper Museum's permanent gallery features a 36-foot long mural that presents selected episodes in the history of height from the pyramids to the present, highlighting themes and buildings that relate to the evolution of the skyscraper and point the way to 21st-century supertalls. It examines the ambition to build high, the technological advances and engineering innovations that enabled that desire, the economics that drove commercial development, the influence of outstanding architectural designs, and the codes and regulations that shaped buildings and skylines.

On the top row is a lineup of the successive structures that held the title of "world's tallest building." On the lower range these are scaled in silhouettes that chart that ascent through the traditions of building in masonry, metal, and concrete, leading up to the first skyscrapers in New York and Chicago in the 1870s and 1880s. From the 270-foot New York Tribune Building to the 2,717-foot Burj Khalifa in Dubai is an astonishing tenfold rise, but the acme of size in terms of overall scale, rather than sheer height, came in the 1970s, with the twin towers of the World Trade Center and the Sears, now Willis, Tower.

The central timeline is illustrated with historical prints and photographs and text boxes that are color-coded: light blue labels describe buildings and events in New York City; green labels refer to Chicago; dark blue in the final panel refers to Asia.

MAPS AND PHOTOGRAPHS OF LOWER MANHATTAN

Thomas Airviews, 1956 and 1976

Stan Ries, 2004

Image Credits:

Lower Manhattan, August 3, 1956

Thomas Airviews, Lower Manhattan

Collection of The New-York Historical Society

The reclamation and reinvention of the waterfront became a chief focus of plans for Lower Manhattan.

Strategies included demolishing the decaying piers and enlarging the island, either by landfill, as at

Battery Park City, or by platforming over the water, as intended, but not executed, on the East River.

The low-rise, mostly 19th-century mercantile buildings that occupied the area adjacent to the piers

were slated for demolition under the city's urban renewal policy. In their place, planners envisioned

development zones of modern office buildings and new residential neighborhoods. The two business

magnets were the World Trade Center complex and the South Ferry and Water Street district.

Image Credits:

Lower Manhattan, May 5, 1976

Thomas Airviews, Lower Manhattan

Collection of The New-York Historical Society

WORLD'S TALLEST BUILDINGS:

SUPERTALL!

1:500 scale models of the world's three tallest buildings

Burj Khalifa exceeds by more than one thousand feet the next tallest occupied building, Taipei 101. In other building categories-in particular TV and broadcasting towers, which often double as tourist sites-two new structures, Canton TV tower and Tokyo Sky Tree, recently topped out at heights of around 2,000 ft.

The red model of Taipei 101 is a wind-tunnel model, created to test the structural design and performance of the tower before it is constructed. Taipei 101, the tallest building in Taiwan, rises 509 m/ 1671 ft to the top of its slender ornamental spire.

The structural model of Shanghai World Financial Center was created by its designers at Leslie E. Robertson Associates to illustrate the skyscraper's structural system. Although the design of the tower was "drawn" and calculated by computers, the model was made to help clients and others visualize and understand the structural system of the frame, core, and outriggers. Shanghai World Financial Center measures 492 m/ 1614 ft to its tapered roof and highest observation deck. Of note: the circular opening in this early version of the tower was changed in the final design.

Taipei 101 wind tunnel model on loan from RWDI laboratory, Guelph, Ontario

Burj Khalifa architectural model; laser cut acrylic on acrylic base, model on loan from Skidmore, Owings & Merrill.

Shanghai World Financial Center structural model on loan from Leslie E. Robertson Associates.

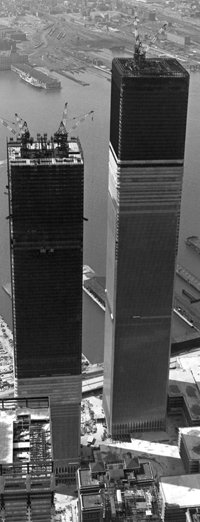

THE TWIN TOWERS AND THE TWENTIETH CENTURY

World Trade Center

Upon their completion in 1971 and 1973, the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center were the tallest and largest skyscrapers in the world. Innovative engineering carried the structures to 110 stories- 1368 and 1362 feet (417 and 415 meters) -creating floors an acre in size, with more than 4 million square feet per building. Except for the contemporary Sears Tower in Chicago, nearly 100 feet taller, but slightly smaller in total area, no skyscraper has ever matched their scale.

To be both big and tall was a phenomenon of the 1960s and 1970s, the climax in the evolution of skyscraper size. The World Trade Center epitomized the ambitions of an era when faith in technology and a fascination with monumentality spurred designs for megastructures and urban master plans. New York's skyline was on the rise, and modernity seemed to matter more than history. Still, considerable conflict surrounded the towers. Writing in The New York Times in May 1966, architecture critic Ada Louise Huxtable noted, "Who's afraid of the big, bad buildings? Everyone, because there are so many things about gigantism that we just don't know."

September 11, 2001 defines our memory of the Twin Towers, and the profound proportions of that tragedy continue to reverberate in New York and beyond. The question of size in the urban scheme remains a complex issue for the future of tall buildings everywhere. As new spires around the world exceed the sheer height of the supertalls of the seventies, none have surpassed the overall scale of the giants of the twentieth century, nor likely ever will.

World Trade Center Wind Tunnel Model

A "pressure tap" model, as in the lower large photograph in this case, measures local pressures on the facade using hundreds of tiny tubes, or taps, connected to a computer.

A "force balance" model measures overturning of the entire building as wind gusts strike randomly.

An "aeroelastic" model, as in the upper large photograph in this case, also measures overturning, but includes the effect of the natural rate of rhythmic rocking back and forth, known as the building's period.

WTC architect Minoru Yamasaki

While now standard practice in the technology of high-rise design, the pioneering effort for the World Trade Center required significant reconstruction of laboratory facilities. Ultimately, three different wind tunnels at three different labs were used: one in the United States (Colorado State University), one in the United Kingdom (National Physical Laboratory, Teddington), and one in Canada (The University of Western Ontario).

THE REBUILDING OF GROUND ZERO

The Freedom Tower

The Museum displays some of the proposed plans for the rebuilding of Ground Zero following 9/11, including a 10-foot scale model for the first proposed design for the Freedom Tower by Daniel Libeskind and SOM.

Completion: 1st quarter 2012

Height: 1,362 ft.; spire: 1,776 ft.; 84 stories

GBA: 3,500,000 sq. ft.

Developer: Silverstein Properties, Inc.

Development Manager: World Trade Center Properties, LLC; an affiliate of Silverstein Properties, Inc.

Architect: Skidmore, Owings & Merrill LLP

Structural Engineers: WSP Cantor Seinuk; Schlaich Bergermann und Partner

MEP Engineer: Jaros Baum & Bolles, Inc.

Construction Manager: Tishman Construction Corporation

Sustainability Consultants: Jaros Baum & Bolles, Inc.; Green Order

LEED Rating: Pending Gold

MANHATTAN MINI MODELS

Crafted by Michael Chesko

[DOWNLOAD Michael Chesko Mini Models Press Release]

CLICK HERE for WIRED Magazine article

The Museum's amazing mini-Manhattan models and their creator Michael Chesko are featured in this month's Wired Magazine's Design section. View dramatic photographs in the online article that juxtaposes New York models with other city models throughout the world, including the Shanghai Urban Planning Exhibition Center's model, which measures 6,500 square feet.

Chesko's models measure 17-3/4 by 20 inches for the Lilliputian Lower Manhattan and 37 by 31 inches for Midtown. The scale of the model is 3/8 inch for every 100 feet, meaning that the 1,250 foot Empire State Building reaches only 4.7 inches tall. The tallest of the tiny buildings are the Twin Towers (still standing in this model) which soar a full 5.1 inches. These models are so small that ten city blocks can fit in the palm of your hand.

In fall 2007, Chesko contacted The Skyscraper Museum with an offer to donate his models. Director Carol Willis's enthusiasm gave him the inspiration he needed to complete a second model of Midtown that covers the area between 8th Avenue to the East River and extends from 25th Street to 60th Street. Aided by books, satellite maps, and the Museum's online visual archive, VIVA, Chesko spent many months carving hundreds of individual buildings, accurately representing these densely packed blocks. Often beginning work at around 7am and not finishing until midnight, Chesko carved and sanded the 382-block Midtown model. Sometimes he would complete four blocks in a single day.

The result of thousands of hours of dedicated labor and craftsmanship, Chesko's delightful miniature models of Manhattan are on public display for the first time at The Skyscraper Museum.

HISTORICAL CONSTRUCTION PHOTOGRAPHS

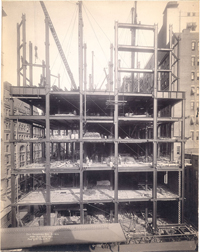

City Investing Building Mural, Weiskopf & Pickworth Consulting Engineers

This photographic image shows the City Investing Building construction site, built between 1906 and 1908. Visible are the structure's steel skeleton, workers balancing on I-beams, and cranes lifting many tons of building material hundreds of feet in the air.

The photograph hangs at the top of the Museum's entrance ramp, which is designed to feel like you are walking on the steel I-beams used in the construction of skyscrapers. As a family, walk up and down the ramp and imagine you are balancing on steel beams hundreds of feet in the air! Also try standing in front of one of the photographs and looking up into the mirrored ceiling. It's as though you're standing at the bottom of the construction site, looking at the new skyscraper reaching up into the clouds.

---

This program is supported, in part, by public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council.

This program is supported, in part, by public funds from the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew Cuomo and the New York State Legislature.