The Skyscraper Museum is devoted to the study of high-rise building, past, present, and future. The Museum explores tall buildings as objects of design, products of technology, sites of construction, investments in real estate, and places of work and residence. This site will look better in a browser that supports web standards, but it is accessible to any browser or Internet device.

A 3D CBD:

How the 1916 Zoning Law Shaped Manhattan's Central Business Districts

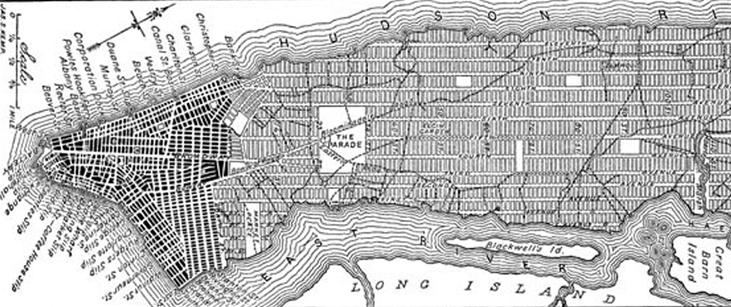

Of the human acts that have shaped the magnificently unnatural geography of New York City and created its unique sense of place, two stand out: the Commissioners' Plan of 1811 and the zoning resolution of 1916 and its later revisions. The first imprinted Manhattan with a two-dimensional plan, a rectangular grid defined by broad north-south avenues and multiple east-west cross streets and by its standard units, blocks of 200 feet by 600 to 800 feet. The second – zoning – determined the city's three-dimensional form by restricting uses by district and, especially, by limiting the maximum mass of a building allowed on a given site.

The early-nineteenth-century Commissioners' Plan was a simple blueprint for the expansion of the city that delineated a separation between two types of space: public and private. An illustration of the 1811 grid makes clear this binary condition; the white areas, which represented streets and an occasional park, were public space while the dark blocks were private. Ownership of property extended from the lot lines straight up into the stratosphere. Thus, a black-and-white diagram of private property versus public space cut horizontally through the city at the level of 100, 500, or 1,000 feet would look exactly the same as the Commissioners' grid.

The Commissioners' Plan of 1811 provisional map, released in 1807

This situation changed dramatically with the passage of zoning in 1916. The ordinance introduced the concept of the “zoning envelope,” which limited and defined the maximum mass (or volume) allowed a building on its particular lot. The zoning envelope was something entirely different than the height limitations long imposed by many European and American cities, including, Paris, London, Boston, and Chicago. Instead of setting an absolute cap on height, encouraging flat roofs and cornice lines, New York’s law sculpted both individual buildings and the skyline in three dimensions. There were a number of different formulas, but in general terms, the law required that after a prescribed vertical height above the sidewalk (usually 90 feet for cross streets or 150 to 200 feet for avenues), a high-rise had to be stepped back within a diagonal plane projected from the center of the street. Balancing that new constraint was a provision that allowed for vigorous commercial development and continued New York’s essential identity as a city of towers: an unlimited height was permitted over one-quarter of the area of the lot.

The resulting stepped-pyramid or "wedding cake" massing typified the city’s high-rises from 1916 until 1961, when the zoning law was dramatically revised. During the building boom of the Twenties, whole ranges of masonry cliffs and mountains shaped by the zoning law sprang up in areas of intensive development such as the East Forties, and West Thirties, especially in the new Garment District where nearly eighteen full city blocks between Seventh and Eighth avenues filled in with office buildings, showrooms, and manufacturing lofts. Downtown, more than thirty-five new setback buildings squeezed into the already dense quarter and several lifted slender towers sixty or more stories into the sky. Soaring landmarks such as Chrysler Building, 40 Wall Street, and the Empire State, the world’s three tallest buildings in 1931, took their shape from the 1916 zoning law.

Left: Zoning envelope created by 1916 zoning law. Right: Zoning envelope illustrating the "grey space" directly above the property.

Beyond the solid forms of ziggurats and towers and the mountainous masses of the skyline, the zoning law also revolutionized the way that the city conceived of private versus public space. The 1916 ordinance created a new dimension of space above and around buildings. This "gray space" (since it was neither precisely public nor private) can be thought of as the negative of the zoning envelope; it comprised the three-quarters of the shaft of air directly above the property lines that the owner was prohibited from enclosing within walls. A hypothetical horizontal section cut through Midtown blocks at the level of five hundred feet would thus look quite different from the two-color diagram of the commissioners' grid; it would show white streets and gray blocks, with only 25 percent blackened to designate completely private space.

The concept of gray space can also be applied to the 1961 zoning ordinance and later revisions, which encouraged plazas, vest-pocket parks, indoor atria, and other amenities. These street-level spaces, which were traded by developers for bonus floors under the incentive provisions, were, in effect, privately financed public access areas. One way to view the history of zoning in New York City is as an effort to reclaim for the public a measure of open space, both on the ground and in the air, that was defined as private under the Commissioners' Plan.

The Laissez-faire City:

Conditions Leading to the Passage of the 1916 Ordinance

The distance of a century and the many subsequent revisions of the first zoning law make it difficult today to comprehend how radical and innovative the concept was in 1916 – radical in the sense that there were few legal precedents for such drastic restrictions on property rights, and innovative in the way it created formulas that limited height and bulk, while still allowing for the construction of tall and profitable towers.

Often referred to by historians as the nation's “first comprehensive zoning law,” New York’s 1916 zoning resolution combined in one ordinance the established precedent of “districting by use” with restrictions on the maximum mass allowed individual buildings. As planning historian Marc Weiss has noted, the New York legislation was also unique because it originated in a movement to regulate commercial property rather than from a desire to protect residential uses.4

In the laissez-faire years before 1916, there were no restrictions on the height or lot coverage of structures other than tenements. With the introduction of the first elevators in office buildings – which finally came in the 1870s, more than a dozen years after they were used in hotels and store like the Haughwout Building – and with the spread of metal-cage and skeleton construction in the 1890s, towers began to stretch well beyond the standard 10 to 13 stories, to 18 to 20 stories or taller. In 1898, the Park Row Building rose 386 feet above the sidewalk to become the world's tallest office building. By 1913, when the Woolworth Building took the title at 792 feet, Manhattan boasted 997 buildings of 11 to 20 stories and 51 buildings of 21 to 60 stories.

From left: Park Row Building, Bankers Trust Building, Equitable Building.

Typically, these early skyscrapers had the appearance of solid blocks extruded straight up above their lot lines. The Flatiron, Adams Express (61 Broadway), and Equitable Building are well-known examples of this type, but there were many other big, bulky office and loft buildings of about sixteen to twenty stories that began to transform areas like Park Avenue South, Union Square, and Fifth Avenue near Madison Square around 1900-1915. In prestigious central locations, such as Wall Street and lower Broadway, high land costs and the potential for premium rents produced even taller towers, often on very small sites. For its new home office, Bankers Trust purchased 4,900 square feet at the corner of Nassau and Wall streets for a record rate of $820 a square foot, demolished the 18-story, 1897 Gillender Building, and shoehorned a thirty-nine-story tower onto the lot. On Exchange Place, really an alley some forty feet wide, buildings of twenty and more stories walled the street, casting it into permanent shadow.

Such densities contributed to conditions that threatened public safety and greatly depressed rents for lower floors. Skyscrapers added to congestion on the streets, bred disease by inhibiting sunlight and ventilation in offices, and presented difficulties for fire control. Nevertheless, many believed there were few alternatives for the urban future. Popular prophecies in cartoons and magazines typically exaggerated current conditions, as in the famous illustration for King's Views, which depicted a city of towers that would be congested, chaotic, and incredibly dense.'

From left: Lower Broadway; "King's Dream of New York," 1908; Equitable Building and Singer Tower.

For decades before 1916, government officials and urban reformers had proposed legislation to curb rampant growth, without success. Calls for limits on heights had already begun in the mid-1870s, when commercial buildings first began to challenge the dominance of church spires on the skyline. In 1884, a bill introduced to the New York State Legislature proposed a maximum building height of eighty feet throughout the city: although that bill failed to pass, another law was adopted in 1885 that restricted multifamily dwellings to seventy or eighty feet in height, depending on the width of the street.

Proponents of the City Beautiful movement advanced aesthetic arguments for limiting building heights. In 1894, architect Thomas Hastings told the convention of the American Institute of Architects: "From the artistic point of view ... there is nothing more unfortunate in the general aspect of the city than the necessarily broken sky-lines of our streets, because of there being no legal limitation as to the height of buildings." Thomas Hastings (architect with his partner John Carrere of many elegant Beaux Arts structures, including the New York Public Library) favored a maximum of eight or ten stories, and he continued to argue for that limit in testimony to the 1913 Heights of Buildings Commission and even into the 1920s.

In 1896, George B. Post and Ernest Flagg – architects who designed skyscrapers that were the world’s tallest office buildings in 1890 and 1908, respectively – also spoke out against the rampant rise of commercial towers. Reporting on their efforts, the American Architect and Building News noted: "The campaign, begun this year by the more thoughtful part of the public and the profession, against the fashion of high building is proceeding with much vigor, and, apparently, with a good deal of success."

Although Flagg would have preferred an absolute limit on heights, he recognized that in some areas real estate pressures made such an approach unrealistic. He therefore proposed that the height of buildings be geared to the width of the street (or a maximum of 100 feet), but that a tower of unlimited height could be allowed to rise on one-quarter of the lot. Having first outlined this plan in 1896, Flagg continued to promote it through debates of the next twenty years, including in 1907 when he designed the 612-foot Singer Building, which surpassed the title-holding Park Row Building by more than 200 vertical feet. Flagg, however, honed to his principles and voluntarily limited the slender Singer tower to 25 percent of the lot. 12

Despite his readiness to accommodate the clamoring of capitalism for a presence on the skyline, Flagg dreamed of a harmonious and horizontal urbanity. As he professed to the 1913 Heights of Buildings Commission:

“To me it is absolutely incomprehensible how anyone can prefer the wild disorder of the American city to the dignified, restrained, and artistic arrangement of the European one, where uniform sky lines of the ordinary buildings give an appearance of refinement and civilization to the streets and afford a suitable setting and a proper background for the public buildings, churches and monuments that rise above them.” 13

Rather than creating a conception of urbanism that responded to the needs of the expanding corporate and commercial city, architects like Hastings, Flagg, and Daniel H. Burnham promoted the paradigm of Paris, especially the Second Empire capital as it had been re-fashioned by Emperor Napoleon III and Baron Georges-Eugene Haussmann, where the boulevards of five- and six-story apartment houses, harmonized by continuous cornice lines, were produced by strict building codes.

Report of the New York City Improvement Commission, 1907. Click here to read the full report.

The French laws were explained frequently in American architectural journals, and many American cities aspired to the Parisian model. In 1903, a group of architects and civic leaders serving on the City Improvement Commission recommended height controls for New York, envisioning new tree-lined boulevards and parks, such as Madison Square, ringed by ten-story buildings. Similarly, the 1909 Plan of Chicago, developed by Burnham for his colleagues at the Commercial Club, banished the skyscraper from its idealized "Paris by the Lake." 15

At the time that New York City was debating zoning, height controls were, in fact, fairly common in American cities. Despite its early role in the 1880s in pioneering the skyscraper form, Chicago set a 130-foot limit on height in 1893 (which was raised to 260 feet in 1902 then lowered to 200 feet in 1910). 16 A table in the 1913 Report of the Heights of Buildings Commission listed twenty-one U.S. cities with height restrictions; many of these were set at 125 feet (as in Boston, where the law dated to 1891), while others ranged from 150 feet, as in Los Angeles, to 225 feet, as in Milwaukee. 7 Recall that in 1913, the Woolworth Building topped off at 55 stories and 792 feet.

Report of the Heights of Buildings Commission, 1913.

In New York City, for whatever reasons—the vitality of its capitalist environment, the desire of corporations for a symbol on the skyline, or the water-bound confines of lower Manhattan—the pressures to multiply the value of land by stacking story upon story were enormous. Although there was another attempt from 1906 to 1908 to control heights by revising the building code, again the proposals of Flagg and other advisers failed to be implemented.18 Urban reformers and others who continued to campaign for controls found greater sympathy at city hall after Fusion party Mayor William J. Gaynor and Manhattan Borough President George P. McAneny took office in 1909, but they still could not force legislation without the support of business and real estate interests.

That support finally began to materialize between 1911 and 1913 and led directly to the passage of the 1916 zoning law. There were two major causes for this shift, both rooted in the drive to stabilize real estate values. The first was the concern about overbuilding in lower Manhattan, both in the increased scale of such mammoth new structures as the Equitable Building at 120 Broadway and in the rate of vacant office space. The second was the lobbying of the Fifth Avenue Association, a powerful group of merchants, hotel operators, and business interests that was organized in 1907 to fight the spread of loft buildings into the fashionable retail district north of Thirty-fourth Street.

Completed in 1915 as the proposed guidelines for the zoning ordinance were being debated, the Equitable Building was one of the last, but most egregious, examples of the problems of unregulated development. The largest office building in the world (in terms of volume: 1.2 million square feet), it covered its entire block – bounded by Broadway, Nassau, Pine, and Cedar streets, an area of just under an acre – and could house 13,000 workers.19 At 542 feet tall, the enormous limestone-clad slab cast shadows across several blocks of prime rental space to the north, including much of the Singer Tower. The Equitable stole light and clients from surrounding buildings. Many owners requested and were granted reductions in tax assessments due to the decline in the value of their properties.20 While the rampant growth represented by the Equitable was hardly new, it dramatized the vulnerability of real estate values to actions not only by immediate neighbors, but also by greedy developers blocks away.

Left: Equitable Building. Right: G.W. Bromley & Co. Atlas of New York, plate 3, 1925.

Unstable property values also were a problem uptown, where retailers on Fifth Avenue were fighting the proliferation of manufacturing lofts on side streets. 21 In the early 1900s, many of the same merchants had abandoned the Ladies' Mile shopping district south of Twenty-third Street after that area had been flooded with lofts used by the garment industry. The immigrant workers who spilled out onto the avenue during lunch hour and other breaks discomforted the upper-class shoppers and the area lost its chic. Store owners relocated farther north among the mansions and high-priced hotels in the area between Thirty-fourth and Fifty-ninth streets—but again, new loft buildings began to cluster near their markets. Property values in the old and largely vacant district south of Twenty-third Street declined sharply, and many people feared that lofts would invade the new area. The Real Estate Record and Guide warned: "People living there would have to move out, abandoning their homes; the principal retail section would be ruined; the hotels would lose their guests, and New York City as a whole would receive a death blow. 2

In 1911, the Fifth Avenue Association appealed for action to a sympathetic McAneny, then Manhattan borough president and, after November 1913, president of the Board of Aldermen.23 A commission was established and a report prepared that recommended that buildings on Fifth Avenue be limited to 125 feet. Although the merchants would have preferred to prohibit manufacturing entirely, the legal grounds for such an action were uncertain. Since the police power of municipal governments to limit heights by districts had been upheld in the courts, the 125-foot cap seemed the better solution, as it would have the effect of making loft construction uneconomical without adversely affecting retail stores.

Left: "Shall We Save New York?" Advertisement, New York Times, March 5, 1916. Right: Final report, June 2, 1916, Commission on Building Districts and Restrictions, Board of Estimate, New York, p.18. Click here to read the report.

The initiative of the powerful Fifth Avenue Association opened the door for a broader view of planning that had been the goal of reform-oriented officials, such as McAneny and his close colleagues Edward M. Bassett, Lawson Purdy, the city tax assessor, and Nelson P. Lewis, the chief engineer of the Board of Estimate. All four men were key figures in drafting the 1916 ordinance and were active in the planning movement nationally.

On February 27, 1913, the Board of Estimate adopted a resolution proposed by McAneny to establish a Committee on City Planning that would investigate the feasibility of regulating the heights of buildings and dividing the city into separate use districts. This committee appointed several advisory groups which held a succession of conferences, prepared a report with specific guidelines, and drafted a bill to be sent to the state legislature that would amend the city's charter to give the Board of Estimate the power to regulate the heights and uses of buildings. 24

After that bill was signed into law on April 14, 1914, a second body was formed to hash out the specifics of the code and to win it wide public support. Officially appointed on June 26, 1914, the Commission on Building Districts and Restrictions methodically began the task of accumulating data, holding public hearings, sounding out the business community, and considering neighborhood requests for changes in the proposed boundaries of districts. The commission's progress was slow, and by January 1916, when the promised report was not forthcoming, the frustrated Fifth Avenue Association threatened independent action—a boycott against suppliers who operated factories within the area between Thirty-third and Fifty-ninth Streets and Fourth and Seventh Avenues. Greater attention from the commission convinced the merchants to drop the boycott, and on March 10, 1916, a tentative report was submitted to the Board of Estimate and public hearings were scheduled.25

After the series of required hearings and yet another round of informal public hearings, modifications were made and subcommittee reports issued in order to ensure the cooperation of various city agencies and officials. 26 Nearly two years later, after considerable politicking and revisions, the zoning resolution came to a vote on July 25, 1916, and passed the Board of Esti-mate by a vote of fifteen to one, with the borough president of Staten Island as the lone dissenter. 27

Final report cover page, June 2, 1916. Commission on Building Districts and Restrictions, Board of Estimate, New York. Click here to read the report.

Why did the ordinance written from 1913 to 1916 succeed when so many earlier efforts had failed? In one sense, New York City was simply catching up to national changes. These same years represented the last phase of Progressive Era reforms and a time of growing professionalism in city planning. At annual meetings of the National Conference on City Planning, which began in 1909, planners enthusiastically promoted the concept of zoning (especially as practiced in some German cities) as part of a program of comprehensive planning. Advocates of zoning were also beginning to feel confident there were sufficient legal precedents to defend its constitutionality. In 1908, Los Angeles enacted the country's first citywide use zoning and successfully defended it in court under the principle of the municipal police power. In 1909, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld Boston's height controls.28

A key factor in the enactment of zoning in New York City, though, was the current depressed state of the real estate industry. The city had experienced record activity in conveyances and construction in 1905 and 1906, but then a sharp decline during the financial panic of 1907. Another banner year in 1909 saw the largest number of building plans ever filed in the Borough of Manhattan. But the boom was followed by a slow, steady decline. In January 1915, the Real Estate Record and Guide reported that the previous two years had been a time of "unprecedented stagnation" and that prospects for recovery were uncertain.29 Vacancies in high-rise buildings south of Chambers Street in 1913 averaged 12.5 percent, and rates for the 2nd through 6th floors ranging from 15.0 to 17.0 percent.30 Given these conditions of oversupply, the real estate industry began to perceive the constraints on space imposed by zoning regulation as a benefit and supported the legislation. 31

The 1916 zoning resolution was thus the product of more than twenty years of debate over the perennial problem of overbuilding, as well as a response to the exigencies of real estate cycles well beyond the control of planners. The alliance that supported zoning included city officials, civic reformers, architects and engineers, real estate and business interests, and their financial institutions. Although owners of residential property in all of the boroughs also figured in the support, they were not a catalyst.32 Each group had somewhat different interests and goals, but the decisive factor in the passage of legislation in 1916 was the desire to protect property values, especially the high and extremely vulnerable values of commercial land in Manhattan. 33

The Impact of the 1916 Law on the CBD

The 1916 zoning resolution established two types of regulation: the separation of uses by districts and restrictions on the height, bulk, and area of buildings. Maps of the entire city were prepared that indicated which regulations governed development at any specific location. The resolution also outlined an administrative procedure for enforcing and amending the code through the Board of Standards and Appeals. 34

There were three categories of uses: Residence, Business, and Unrestricted. Divisions were straightforward. Unrestricted districts meant exactly that. Residential districts permitted houses, apartments, hotels, clubs, schools, churches, and other cultural and institutional uses. Small-scale businesses, such as doctors' offices, dressmakers, and artists' studios, also were allowed. Business districts encompassed a broad range of commercial functions but excluded any industry that was "noxious or offensive by reason of the emission of odor, dust, smoke, gas, or noise." 35 Among the many uses expressly forbidden were brewing and distilling, fat rendering, fertilizer manufacture, garages for more than five vehicles, sawmills, and stockyards. Other types of light manufacturing, such as the garment trades, were permitted, but limited to no more than 25 percent of the total floor space of the building.

City of New York Board of Estimate and Apportionment, Use District Map, 1916.

In general, the mapping of use districts tended to reinforce, rather than alter, existing patterns. Most of the east side of Manhattan was zoned either as business or unrestricted, except for Fifth and Park avenues and their crosstown streets near Central Park, which were residential. The Upper West Side was solidly residential, save for Broadway and Amsterdam and Columbus avenues. The majority of sites below Twenty-third Street were unrestricted.

The financial district was designated for business, as were some of the principally residential areas of Greenwich Village and the tenement districts of the Lower East Side. Midtown above Twenty-third Street and between Second and Tenth avenues was almost entirely a business zone, except for the Unrestricted area west of Seventh Avenue from Thirty-fourth to Forty-second streets (which became the garment district in the 1920s). Consequently, the expansion of the lofts and activities that had precipitated the protests of the Fifth Avenue Association was limited, although light manufacturing activities were still possible in 25 percent of a mixed-use building.

Height and Bulk Districts and the Zoning Envelope

The concept of the zoning envelope was the most innovative aspect of the 1916 ordinance. Although, as the reformers noted, the principle of regulating bulk had precedents in Parisian and other European building codes, at the high-rise scale introduced in New York City, the formula for a maximum spatial envelope was entirely new. The idea of stepping back the upper floors of high-rises to allow more light to reach the street had first been suggested by American architects in the 1890s, and in 1907 and 1908, when several prominent figures, including David K. Boyd, had proposed a formula for setback massing. That idea, combined with Flagg's plan for allowing a tower on one-quarter of the site, became the basis of the zoning envelope.

There were five formulas regulating the height and bulk of buildings. All were based on the width of the street and on the setback principle, but each resulted in a slightly different spatial envelope. For example, in a "1 ½-times district," if the street were 100 feet wide, the facade could rise sheer to 150 feet before the first setback. Above that level, the mass had to step back in a ratio of 1:3, that is, a one-foot setback for each three feet of additional height. In a "two-times district," if the width of the street were 100 feet, the building could reach 200 feet before it had to begin stepping back at the rate of one foot for each four feet of additional height.

Final report, June 2, 1916. Commission on Building Districts and Restrictions, Board of Estimate, New York, 258-9. Click here to read the report.

All of Manhattan was liberally zoned as 1, 1 ½, 2, 2 ½ -times districts, except for the corridor of Fifth Avenue between Thirty-second and Fifty-ninth streets and two principally residential areas in the northwest corner of the island, Washington Heights and Inwood, which were designated as 1 1/4 -times districts. The different formulas produced many permutations because both the width of streets and avenues and the factor of multiplication varied. In general, buildings on avenues could rise sheer for about 14 to 18 floors. On side streets, they were generally 9 to 12 stories before the first setback.

The graphic guidelines were drafted by George B. Ford, an architect and engineer who served as the secretary for the Heights of Buildings Commission and as a consultant to the Commission on Building Districts and Restrictions, as well as to the Planning Committee. Precisely how Ford, who had worked in the office of George B. Post, developed the formulas and to what extent he consulted and compromised with the real estate community are questions that deserve in-depth research.

Final report, June 2, 1916. Commission on Building Districts and Restrictions, Board of Estimate, New York, 260-1,4. Click here to read the report.

Ford's diagrams were spare line drawings, but the building envelopes were generous. The volume within the setbacks, together with the 25 percent area permitted for a tower, added up to the potential for very high densities, especially for buildings on large sites. Yet the liberality of formulas ensured their success. Unlike other cities, such as Chicago, which capped heights, but then kept raising and lowering them under pressures from real estate interests, New York City maintained its standards for forty-five years before it reduced, rather than raised, the permissible bulk.

City of New York Board of Estimate and Apportionment, Height District Map, 1916.

Another system, area districts, controlled the lot coverage, or the portion of the rear or sides of the lot that was kept open in yards or courts. There were five area districts, A through E. All of Manhattan was designated either A (for waterfront areas, in which coverage of 100 percent of the lot was allowed) or B (which called for either courts or rear yards approximately the same as those required by the Tenement House Law).38

Setback Formulas Shape the Streets and Skyline

As asserted in the opening of this essay, the 1916 zoning law was a fundamental force in reshaping the city’s skyscrapers and creating the character of the Manhattan skyline. However, its prospective impact took some time to be fully comprehended, even by its contemporary planners and architect advisors.

The first visible effects were highly practical and played out in individual buildings. Owners and architects found that, if they wanted to exploit the maximum envelope allowed for the lot, the shape of the building was, in effect, predesigned by the code. New construction was limited in New York during the period following the early years of the passage of the ordinance, but when the post-war building boom began in the mid-1920s, the setback massing began to appear across the city.

From left: Shelton Hotel, Barclay Vesey Building, New York Telephone Building, The New Yorker Hotel.

Fine early examples such as the 1924 Shelton Hotel and the Barclay Vesey New York Telephone Building were followed by dozens of multi-terraced, ziggurat-like forms such as the Paramount Building in Times Square, the New Yorker Hotel, and block after block of high-rise “urban fabric” in the Garment District. Increasingly, after about 1923 or 1924, many designers began to treat the setback as an aesthetic. Buildings were conceived as simple sculptural forms, a diminishing series of stacked boxes with their edges often emphasized with ornamental banding. Today, we associate this treatment with the Art Deco style, but in the Twenties numerous other terms were used, including the "setback style," "New York style," or simply “modern."

The key to understanding the power contained within the 1916 zoning law to shape both building forms and the impact on the skyline were a 1922 series of drawings of the “Four Stages of the Maximum Mass of the Zoning Envelope” created in 1922 by the architectural delineator Hugh Ferriss, working in collaboration with the architect and zoning advocate Harvey Wiley Corbett. The Ferriss drawings, which were widely exhibited, as well as published in the March 19, 1922 New York Times Magazine, as well as in may other publications, exerted an enormous influence on contemporaries.

Hugh Ferriss, "The New Architecture," The New York Times Magazine, March 19, 1922.

The drawings illustrate the step-by-step shaping of the maximum mass allowed by the zoning law into a profitable commercial structure. The first stage with sloping planes represented the angle of light required to preserve some sunlight on the streets and included a tower that filled the allowable one-quarter of the site. In the second stage, light courts were cut into the mass, and in the third, diagonal planes were squared off and the multiple steps of the upper levels were simplified for more economical steel construction and elevator circulation. The final stage presented an imposing structure with a central tower about 1000 feet high, around 70 stories, flanked by setback wings of 40 stories.

The power and inchoate modernity of Ferriss's diagrams derived from their simple sculptural mass and monumentality, and many architects and planners testified to their immediate influence on skyscraper design and on their conception of the future city, as I detail in my 1986 article, "Zoning and Zeitgeist: The Skyscraper City in the 1920s."

The drawings also made abundantly clear the benefits of a large site. The limitation of the tower to one-quarter of the site encouraged the assemblage of smaller parcels of land into large lots. To erect a very tall tower like the Chrysler Building or the Empire State, a lot had to be at least 150 by 200 feet for the tower to contain enough office space to be profitable and still devote the requisite space for elevators and other service areas. The enormous size of the Empire State Building's site, 197 by 425 feet, for example, meant that its shaft could expand to 100 by 212 feet. This was large enough for the 58 elevators necessary to deliver first-class service to the building's 86 stories, while allowing each of the major tower floors to offer about 15,000 square feet of rentable space. Thus, the zoning formula, together with the economics of maximizing rental space, made larger buildings logical. Such large sites were rare, especially downtown, however, due to the divided ownership of the small parcels that were the legacy of the Commissioners' Plan of 1811 and because of high land prices generally.40

Nevertheless, in the booming spirit of the Roaring Twenties, many architects predicted that Manhattan would evolve into a metropolis of huge setback structures covering one or more full city blocks. Each superblock would be an autonomous "city within a city," linked by efficient mass transit and multilevel highways. In his 1929 book The Metropolis of Tomorrow, Hugh Ferriss imagined a new urban topography of mountainous towers set at half-mile intervals and surrounded by abundant light, air, and open space.41 Perhaps the most regimented vision of an urban vista extrapolated from the setback formula was the 1929 image created by Chilean architect Francisco Mujica, entitled "Hundred-Story City in the Neo-American Style." 42 Other prominent New York architects, such as Harvey Wiley Corbett and Raymond Hood, offered visionary proposals for new precincts of setback skyscrapers that separated rail, wheel, and pedestrians on different levels of the city and upper level terraces and gardens, even as they were designing a three-block urban complex and full-block tower at Rockefeller Center.

From left: Hugh Ferriss, Francisco Mujica.

In the 1920s, zoning became a form-giving principle behind both a new approach to skyscraper design and a new vision of the modern metropolis. The idea that the whole city—private property as well as public space—could be subject to public controls inspired a new sense of power and optimism. Hood called zoning "the first great step forward into community planning under which the individual owner submits to the public welfare," and Ferriss proclaimed the law regarded building operations "not from the point of view of the individual plot, or owner, or designer, but from the argus-eyed view of the city itself. 43 These men saw zoning as a democratic dimension in city building because it protected the public good over the formerly unrestricted rights of property. In the unprecedented control that zoning afforded to shape both the individual building and the city plan, they perceived the possibility of not only regulating further urban growth but also rationalizing it.

No such monumental order had been intended, or even foreseen, by those who drafted the law. In 1929, Ford recalled how in developing the different formulas for the zoning envelope, in addition to studying how to bring the most light and air into the street, he and his staff had worked to achieve a variety of architectural effects, including towers, terraces, and gables that "would permit all the variety and spontaneity of treatment that we are reveling in today." Ford made the realistic assumption that, for the most part, new buildings would replace older ones lot by lot, rather than block by block.

The zoning ordinance was a practical, not a visionary, document. No particular ideal of urbanity or architectural aesthetic motivated it, as had been the case with the City Beautiful movement, and as a result, it offered no inspiring visual imagery – no "big plans" with the "magic to stir men's blood," as in Burnham's famous phrase, nor was it a philosophical critique of the skyscraper and its place in civic life. Such concerns were considered insufficient legal grounds for the municipal government to exercise police power over private property. Crafted in compromise by a broad coalition of interests, zoning had to be fairly modest in its restrictions and readily amendable.

Indeed, the major criticism of zoning in the mid-1920s by many of the original reformers, such as Bassett, Purdy, and Ford, was that it was far too liberal. In the years immediately after its passage and during the postwar period, support for zoning had been nearly unanimous; but the extraordinary building boom that began in New York City in late 1921 and that lasted into 1930 and 1931 (during which time the city nearly doubled its total office space) clearly demonstrated the extreme densities that could occur within the regulations. Variances were easily won, and height districts were increased in a number of areas, including Eighth Avenue from Thirty-third to Fifty-sixth streets.45As construction broke records in 1925 and 1926, calls for stricter regulations became more insistent, and a major debate over how to curb the skyscraper was waged in both professional circles and in public forums. In 1926, Mayor Jimmy Walker appointed the City Commission on Plan and Survey, a forerunner of the City Planning Commission, to recommend changes in the resolution. However, no major actions to reduce building heights or bulk were passed during the boom.

Was the 1916 zoning resolution a success or a failure? The answer is different for idealists and realists. Some of the disparity is suggested in the comments of Bassett in a discussion of the revisions he proposed for his own legislation in 1931:

New York City did not advance very far when it adopted the two and two and one-half times limit with setbacks and 25 percent towers, and there may be many who say that with this limit the skyscraper problem was hardly touched, that skyscrapers are being erected as high as they probably would have been without zoning, that the total rentable floor space in the high building blocks has not been affected, and that street congestion is as great as if buildings had been left unregulated. These criticisms are partly true. On the whole, however, the results of zoning have been to give greater access of light and air to separate buildings and to the street. The opportunity of blanketing one building by another has been lessened. Architecturally New York has been greatly improved by zoning. What more can be done? Nearly all will admit that something ought to be done. But to say what ought to be done and to say what can be done are two quite different things. 46

The temptation to measure the 1916 ordinance in current terms—for example, to criticize its restrictions on development as weak or as lacking a "vision" of the city—should be avoided. Zoning was (and is) not planning, and viewed in its proper historical context, the first ordinance was a tremendous, not a timid, step. For the first time, there existed a real tool that could shape actual masses and spaces and that applied to the entire city. Zoning thus changed the mind-set of many who speculated on the urban future, infusing them with a new sense of efficacy.47

Not the least of the law's legacy was its influence on the visual experience of being in Manhattan's most densely developed commercial districts. One of the most extraordinary effects in any modern city occurs on Midtown cross streets, where the constructed canyon walls shave back like eroded cliffs and frame a sliver of open space that seems a "slice of sky." Because these streets typically end at water and there is often nothing visible on the distant shore, one has the sense that the road and sky meet without mediation, like the vanishing point of a one-point perspective drawing. The narrowness of this space makes it read as a positive shape rather than as a void. The slice of sky is often radiant with light, as in early summer, when, around eight in the evening, the sun sets precisely on the axis of the cross streets. There is hardly a more thrilling experience in architecture than to walk along an avenue during these minutes and to look west at each intersection to see the raking light across masonry facades and the pastel colors of the sunset.

These effects are produced by the rigid rectilinearity of the nineteenth-century Commissioners' grid and the richly plastic massing formulas of the 1916 zoning ordinance. Both artificial systems were imposed on the island with the purpose of turning land into property; in doing so, they created Manhattan's magnificent morphology.

The contributions of nearly twenty conference speakers were collected in a book, edited by Todd W. Bressi (New Brunswick, NJ, Center for Urban Policy Research, 1993). The book is difficult to find today, outside of a few used booksellers and university libraries.