The Skyscraper Museum is devoted to the study of high-rise building, past, present, and future. The Museum explores tall buildings as objects of design, products of technology, sites of construction, investments in real estate, and places of work and residence. This site will look better in a browser that supports web standards, but it is accessible to any browser or Internet device.

PREMISES

IS DENSITY A STRATEGY FOR SUSTAINABLE CITIES?

In the world of globalization, "winner" cities grow affluent and attract newcomers of all classes.

As successful cities add population and richer residents consume more personal space, how can the

urban environment sustainably accommodate these numbers? In conjunction with its current exhibition,

"Vertical Cities: Hong Kong | New York," The Skyscraper Museum convened an international symposium on

the extreme vertical urbanism of Hong Kong and Manhattan.

"NY-LON-KONG" is the term Time Magazine coined to describe the networked triad of financial capitals they predicted would dominate in the 21st century.�New York, London, and Hong Kong were identified as winner cities because they are adaptable, resilient, efficient, and exciting. Of the trio, though, only two share the striking physical characteristic of vertical density. New York has historically been the world's premier skyscraper city, but it has recently been eclipsed by Hong Kong in both the number of towers and average height of new buildings. Apartments for both public housing and the private market commonly rise 50 to 60 stories or taller. Hong Kong's built environment stacks its 7 million people into high-rises, averaging 70,000 per square mile -the same density as Manhattan. Prices of residential property and office space in both cities rank among the most expensive in the world. Is vertical density connected to affluence? Is it a positive goal for urban planners?

WHAT IS "VERTICAL DENSITY?"

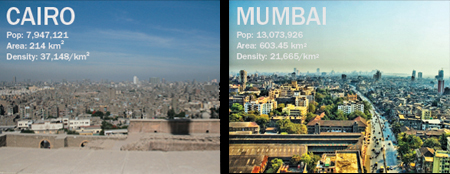

Urban density has two dramatically different expressions in many world cities: one on the ground plane, the other in the skyline. The world's densest major cities -Hong Kong, Cairo and Mumbai- represent wildly disparate models of urban development in the vertical and horizontal dimensions. Cairo and Mumbai -cities of widespread poverty- have average densities of 96,000 and 56,000 per square mile, respectively, but their extreme concentration is spread homogenously in low-rise buildings in an environment of crowding and congestion: this is the density of poverty.�

Hong Kong's density, both commercial and residential, is housed in high-rises. Averaged over its full 426 square miles, the population would be 17,000 people per square mile. However, more than three-quarters of Hong Kong territory is preserved as natural landscape, and the cumulative built area is limited to 100 square miles. By confining its 7 million inhabitants to a mere 23% of its land, Hong Kong's land-use controls and development strategies concentrate people on a small percentage of that land, even in the master-planned vertical communities in the New Territories. Transit-based development makes these New Towns of dozens of identical apartment towers, typically fifty and sixty stories rising above a podium shopping mall, as densely occupied as the older central areas of Kowloon and Hong Kong island. Throughout the territory and across income levels, from public housing to the luxury towers, an average of 250 units per acre in large-scale developments is common.

By contrast, across the five boroughs, New York's density averages 27,000 people per square mile, and the proportion of park and open space is only 25 percent-the inverse of Hong Kong. With the exception of Manhattan, New York proper is largely low-rise.�

LEARNING FROM HONG KONG

Top: Hong Kong skyline as seen from Wan Chai, with IFC at far right

Bottom: ICC sectional rendering showing tower and transit connection

If Hong Kong has succeeded by embracing Manhattan's "culture of congestion" as Rem Koolhaas described the energy and drive of New York in the early twentieth century, what values might Gotham recognize in Hong Kong's recent rise? Development in Hong Kong in the past decades shows that planned urban growth can accommodate the pressures to intensify central districts while creating commuter communities of dispersed, but remarkably dense new housing in the outer districts and New Territories. Some achievements New York might emulate are investments in infrastructure that have created a seamless 23-minute ride from the top-ranked international airport to the central business district and middle-income housing estates of 250 units an acre that are served by and help to finance mass-transit railways.

LAND MANAGEMENT

There is a false clich� in both cities that explains their skylines as a result of their island identities, claiming that the limited space forced buildings upward into the vertical. While rampant capitalism and real estate markets increased land values, the density of the skyline and the proportion of open space is a function of government decisions that are culturally and politically constructed. New centuries present new problems and possibilities. What are the new priorities and strategies for urban planning?�

VERTICAL COMMUNITIES

Tseung Kwan O housing estates and section drawing showing transit connection

Whether luxury, middle-class, or public, Hong Kong housing is high-rise and high density. The Hong Kong government leases land for development and keeps the value of land high by encouraging residential density in conjunction with mass transit. These housing estates were built by major real estate companies, working in cooperation with the mass-transit rail company, the MTR. Rail stations form the hub for a multi-level commercial shopping mall that also serves as the podium base for the apartments that often number a dozen or more identical towers of 40, 50, or 60 stories.�

Left: Tung Chung housing estates, Right: Luxury Apartments in Union Square, Hong Kong

SUSTAINABLE SOLUTIONS

For many urbanists and civic activists today the term "density" has a negative connotation of crowding, congestion, poverty, and inadequate public space. But the examples of Hong Kong and Manhattan and their 70,000 people per square mile suggest that high density can correlate with affluence. What kind of density works to make cities vital? What is the balance between future growth and sustainable urbanism?

Successful cities- the "Ny-lon-kongs" -attract a creative workforce and newcomers of all classes. As they become more prosperous, though, residents desire and consume more personal space. How can growing cities cope with their finite boundaries and still accommodate the appetites of affluent people for more private space, amenities, and an expanded public realm?�Doesn't simple math require a rethinking about the issues of density? How can the urban environment sustainably accommodate these new numbers?The conference took as given that New York and Hong Kong will grow in population and that the challenges of global markets as well as of global warming will affect how governments and the public must deal with the pressures of growth. Also understood was the essential value of the history and heritage of the cities' identities past and future. The programs explored how Hong Kong and New York can profit from a dialogue on their unique and united cultures of urban density.