The Skyscraper Museum is devoted to the study of high-rise building, past, present, and future. The Museum explores tall buildings as objects of design, products of technology, sites of construction, investments in real estate, and places of work and residence. This site will look better in a browser that supports web standards, but it is accessible to any browser or Internet device.

HERITAGE TRAILS

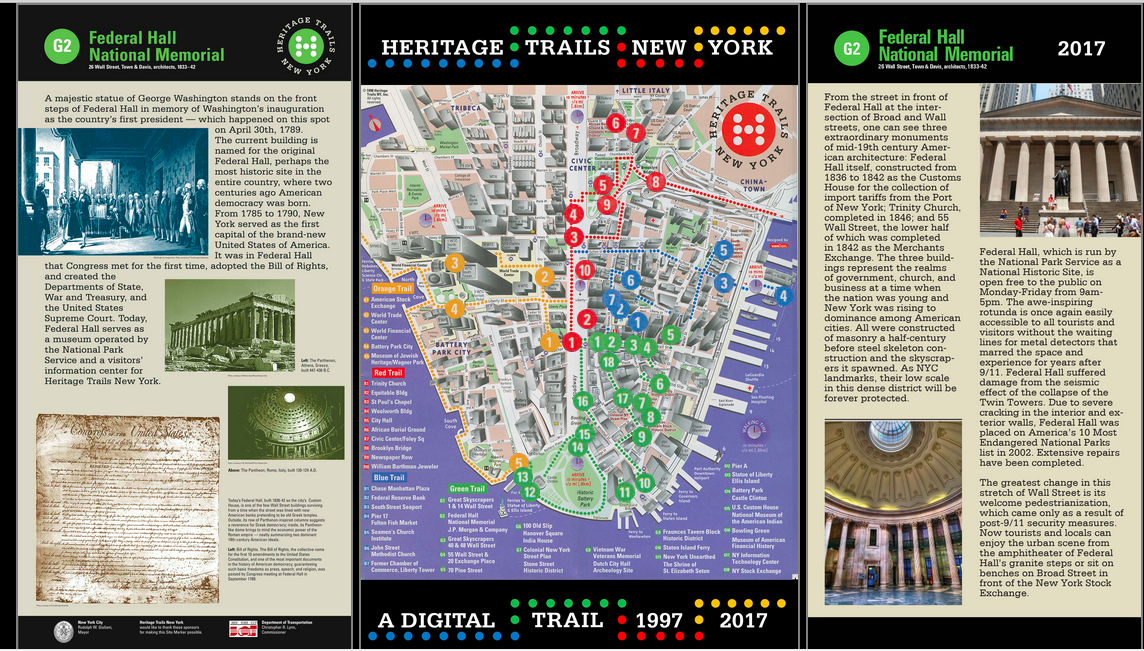

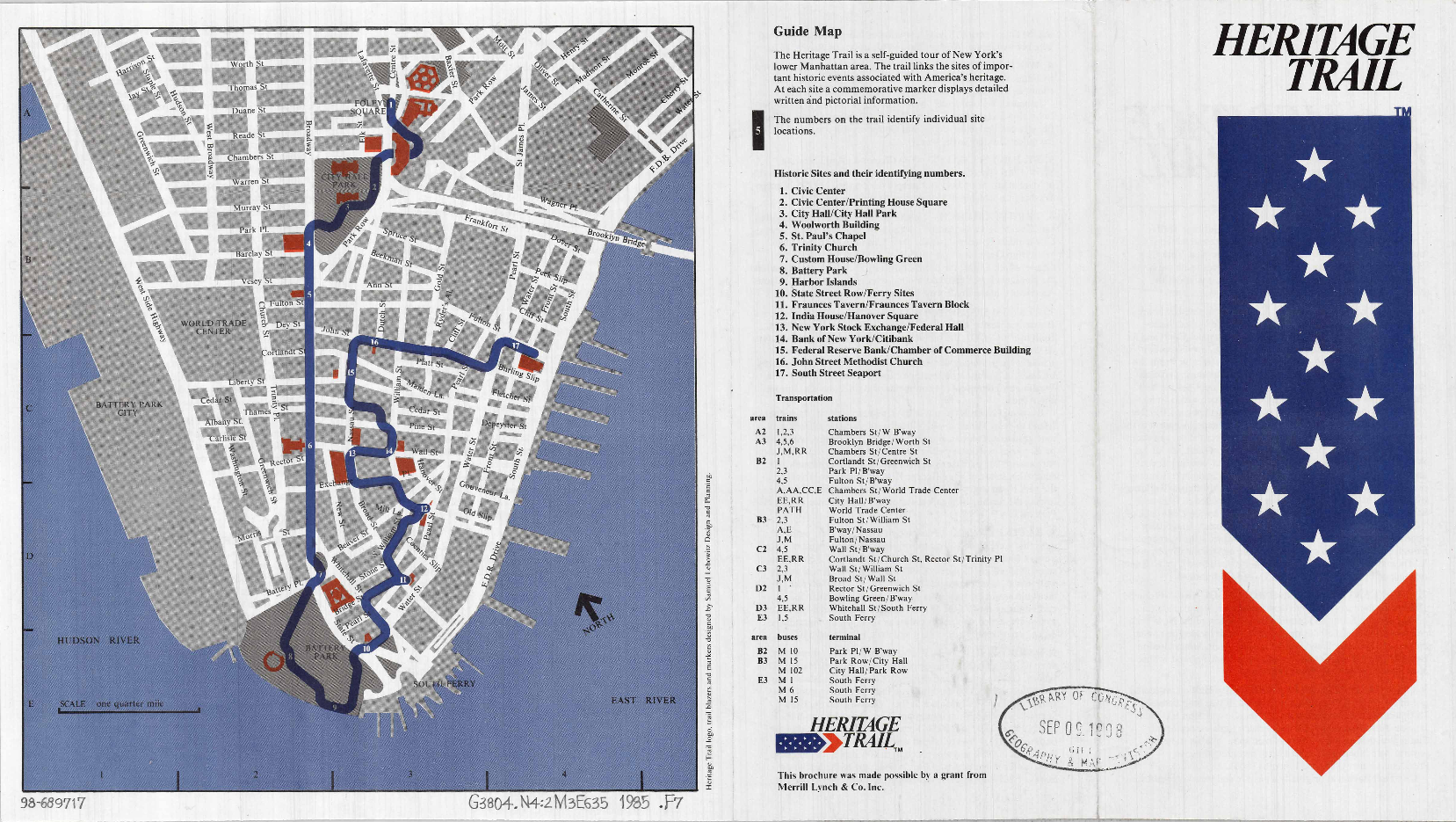

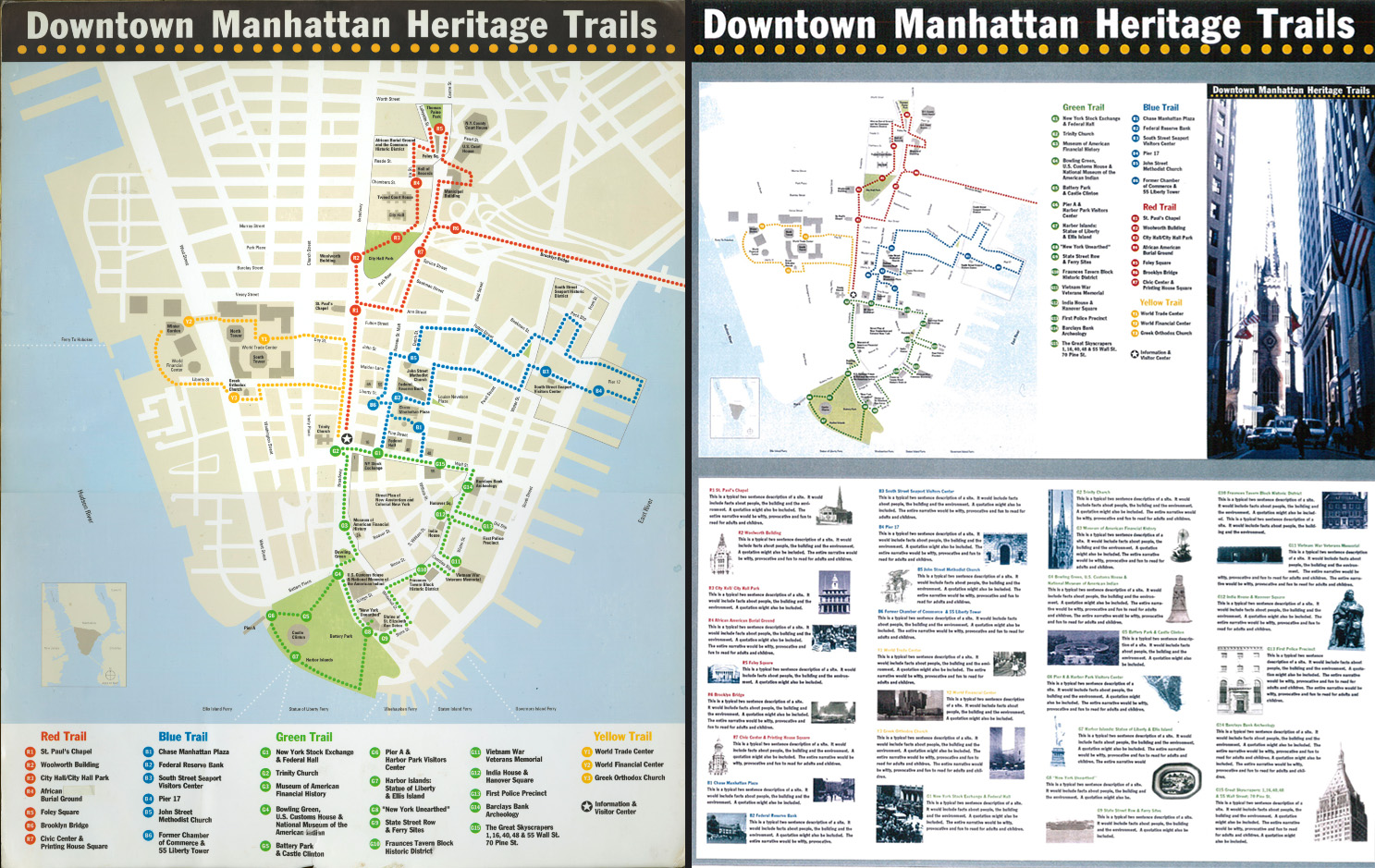

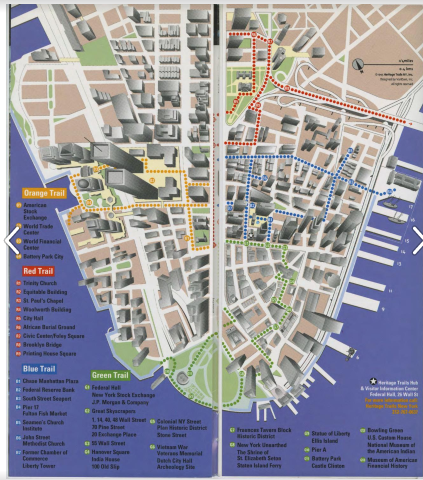

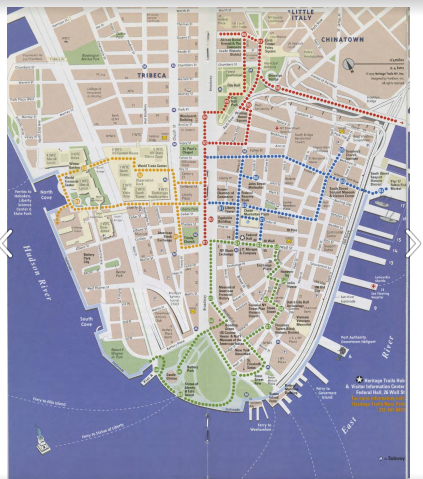

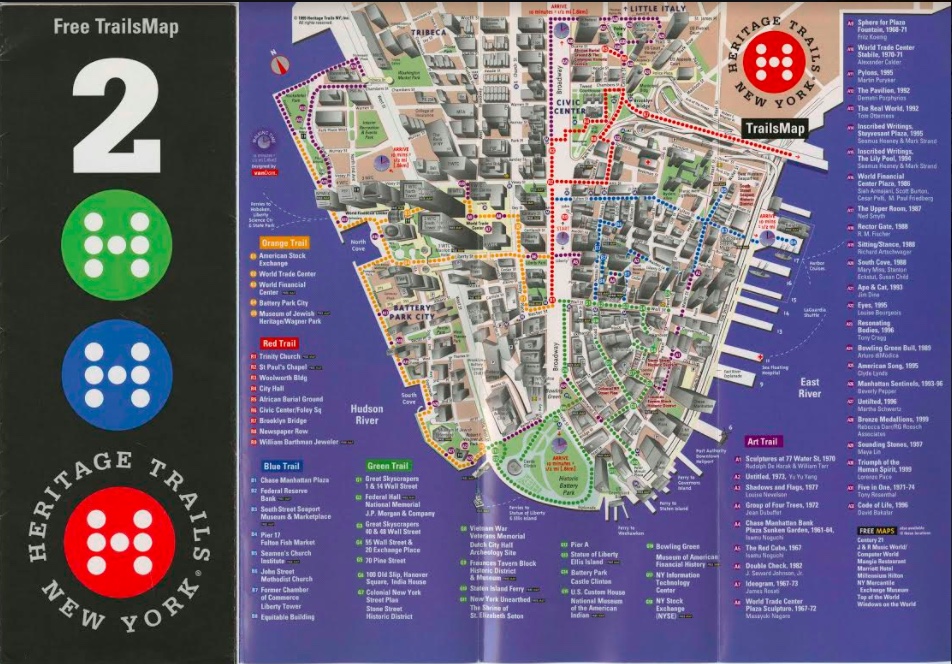

Heritage Trails New York (HTNY) was a landmark public history project of the mid-1990s focused on lower Manhattan – principally the square mile at the tip of the island, south of City Hall Park – the area that encompasses the historic core of the colonial city and the power center of the Financial District. In 1998, when the project was largely complete, Heritage Trails comprised 40 site markers – stanchions and panels with images, interpretive texts, and a innovative 3D Downtown map. These were keyed to four trails, denoted by the colors Green, Blue, Red, and Orange, which tourists could follow with a free map pamphlet that could be acquired at multiple information centers. The original concept of creating a marked linear path via colored dots on the sidewalk was only partially realized and stayed in place only through 2000, after which the 2,376 Scotchprint circles were power-washed from the streets, and almost entirely lost to history.

History is rewritten often, both by historians and by subsequent events. The brief life of Heritage Trails New York, though, was surprisingly short-lived given the considerable energy, talent, and funds expended on it. Without the cataclysmic disruption of 9/11, which changed utterly the trajectory of Downtown from an evolving neighborhood to Ground Zero recovery, perhaps Heritage Trails would have become as much a fixture of Downtown’s identity as the Freedom Trail is in Boston. But timing mattered: conceived in 1994 and completed five years later, Heritage Trails New York (HTNY) did not survive as a “brand” after 9/11. And because Heritage Trails was created in the years just before websites became common, there remains scant digital record of the project. Like the trails themselves, which have vanished from the Downtown maps, the story of Heritage Trails has become invisible.

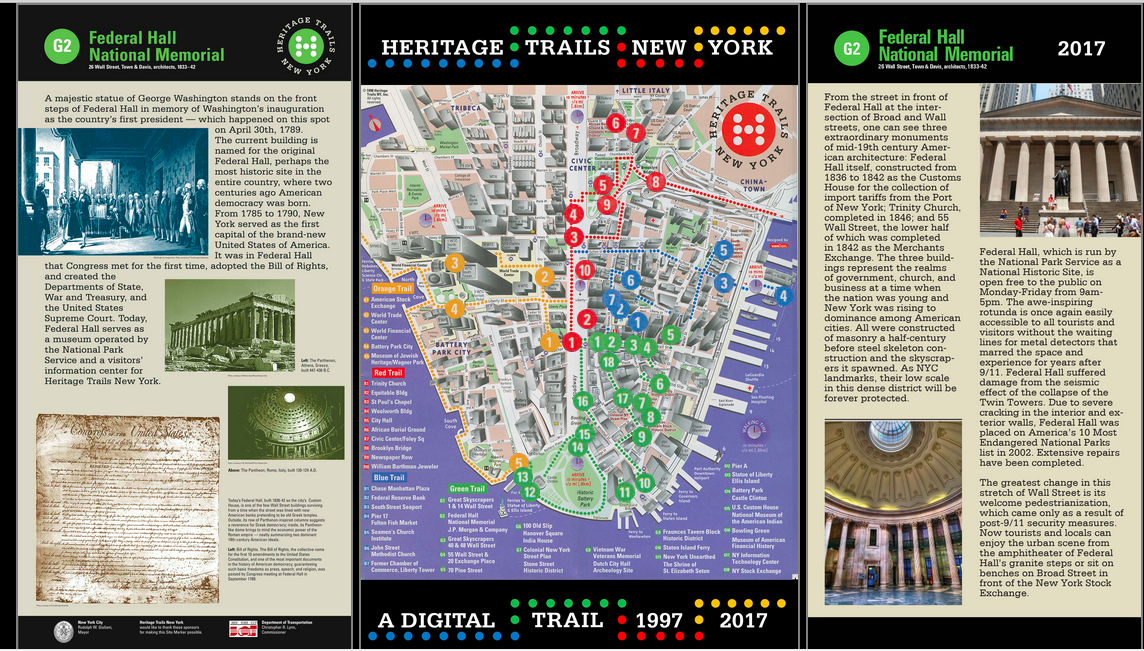

For this reason, The Skyscraper Museum undertook to create a digital footprint for Heritage Trails. Our project had two main parts. First, to find the digital design files and reconstruct the original marker panels from the files we acquired from the Downtown Alliance and the project's graphic designers. To these we added a contemporary panel that addressed the events of the two decades from 1997 to 2017. We keyed these pairs of panels to the 1998 Heritage Trails map, making the numbers of the markers interactive in a way that allows a visitor to view the trails virtually on a computer screen or to use the website to navigate the original trails on the city streets and read the then-and-now markers on a mobile screen.

The second aspect of our work was to document the Heritage Trails project and to create an archive, both physical and digital. The key collection of documents we acquired were the Heritage Trails records and personal papers of Richard D. Kaplan (RMK), the driving force of the project, who died in January 2016. We created an inventory of the items and a detailed chronology of the project.

In addition, we sought out the key members of the small team responsible for creating the Heritage Trails, including the non-profit’s staff, its graphic designers, map maker, consultants, and others involved with the project or other downtown efforts supported by Kaplan. We interviewed these individuals and transcribed their reminiscences or asked them to write essays about their work. From these and other sources we developed the following narrative of the project. The account draws heavily on long quotes from interviews of the key participants and from important documents in the RMK papers. These documents can be viewed are reproduced in pop-up windows which allow a full reading of the source material. Who Created the Heritage Trails and

Why? Heritage

Trails was the brainchild of Richard D. Kaplan, an architect by training and

the son of the wealthy businessman and philanthropist Jacob Kaplan, who in 1947

established the private foundation the J. D. Kaplan Fund to support a wide

range of organizations in the arts, civil rights, parks, and preservation. Renown

for providing early “seed money” to transformative projects, all the Kaplan

family could indulge their interests and enthusiasms at the same time that they

took their grant-making very seriously. Indeed, the

earliest dated document in Richard Kaplan’s Heritage Trails files is a March

1994 grant proposal to fund a 3-D computer model of lower Manhattan that had

been created by architect and planner Michael Kwartler

for the Kaplan-funded Urban Simulation Lab at the New School, which was to be

used in part as a tool to study how policy changes such as zoning and tax

incentives could be used to revitalize lower Manhattan. Memos of

May or June 1994 refer to the Heritage Trail as one aspect of the larger

“Downtown Lower Manhattan Project.” Richard wrote, “The second endeavor is to

create a task force which looks specifically at the tools needed for a mature

city. Tools meaning “zoning and tax policy” and mature city meaning “lower

Manhattan (south of Chambers Street).”

When Peyser began working with Richard in the J.M. Kaplan Fund office in late May or June 1994, the pace of the project accelerated. A key event was a convening of The Friends of the Heritage Trail on June 13, 1994 at the offices of Claude Shostal, President the Regional Plan Association (RPA) and the former Commissioner of Cultural Affairs of the City of New York, appointed in 1976 – timing which placed his name at the head of the Bi-Centennial Heritage Trail project. Others in attendance included Samuel Lebowitz, the graphic designer for the first Heritage Trail markers, Roland Peracca of Chase Manhattan Bank, Barbara Christen, then president of the DLMA, Gaby Rattner of the RPA, and Nadine Peyser. As a result of that meeting, the memo stated: “it was agreed that the J.M. Kaplan Fund, under the direction of Richard Kaplan, would lead the initiative to re-launch an up-graded Heritage Trail.”

Materials in the Art Commission (PDC) archives provide detailed information on the design. The presentation provides a description of the composition of the marker panels, as they were then conceived:

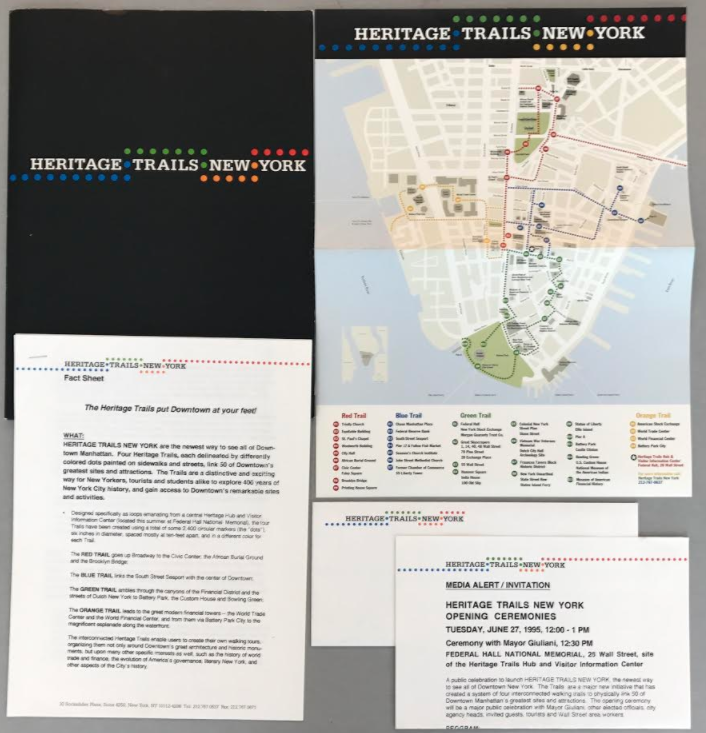

Heritage Trails Opening Ceremony On June 27, 1995,

Heritage Trails made its public debut at a festive press launch held on the

monumental and historic steps of Federal Hall. Richard Kaplan made a speech,

followed by remarks from Borough President Ruth Messinger and Mayor Rudolph

Giuliani. The program, which was produced by the event planner Karin Bacon,

included the Satchmo & Company jazz band, costumed dancers, and stilt

walkers who teetered across the street to unveil the first official Heritage

Trails marker in front of the historic headquarters of the financier J. P.

Morgan at 23 Wall Street. The group then took the inaugural walk of Heritage

Trails up Wall Street to Trinity Church where they were welcomed with music and

an outdoor reception.

The schedule of the program and background on the Heritage Trails project was described in a press

packet. As the Media Alert

explained: · Physically link—like a

string of pearls—the gems of Downtown’s historic buildings, significant

attractions and cultural events; · Establish a user-friendly pedestrian walking system, linking the

Trails with proposed local bus loops and increased ferries along the

waterfront, and with major tourism attractions, such as the Statue of

Liberty/Ellis Island, World Trade Center, South Street Seaport, and Wall Street; · Create a Trails-based curriculum for schoolchildren; · Promote and market Downtown’s diverse attractions; · Provide an economic stimulus for Downtown’s retail, commercial

and residential concerns.

As a history buff, Richard Kaplan relished the location of the gathering on steps of Federal Hall, next to the monumental bronze statue of George Washington that marks the site of the first inaugural Presidential address. He introduced himself as the Founder and President of Heritage Trails New York, and the press release further identified him as the Co-Chairman of the J.M. Kaplan Fund, as well as the Chair of the Alliance for Downtown New York’s Committee on Tourism, Historic Preservation, Urban Design and Parks, a new position, since the BID had just become an official entity in 1995.

The interim Heritage Trails Hub and Visitor Information Center also opened for the launch and the summer tourist season. It was installed within the information area of the Federal Hall National Memorial at 26 Wall Street, the magnificent masonry monument completed in 1842 as the Unites States Custom House, but called “Federal Hall” because it was erected on the site of New York’s original colonial-era City Hall, the building that served as first capitol, the site of George Washington's inauguration, and the place where the Bill of Rights was introduced in the First Congress. Operated since 1939 by the National Park Service, Federal Hall is a national memorial, open free to the public: them as now, it was open only from 9-5 on weekdays. To extend those limited hours, the press release noted, “as a convenience for its users and an important visitor service for New York City, Heritage Trails New York has provided that this summer Federal Hall…will be open to the public on weekends for the first time.”

Richard Kaplan noted in his draft speech that the launch represented Phase 1 of the Heritage Trails, which was to be a two-year Demonstration Project, which would solicit feedback as to “the best paths and the best materials before we install the ultimate, permanent Heritage Trails.” The Fact Sheet suggested that Phase 1 included “placement of all Trail markers” – although how many this meant is unclear. Phase 2 had a much more ambitious agenda, which would include: “construction of a permanent Heritage Trails Hub and Visitor Information Center, with exhibitions and multi-media activities; installation of all additional Site Markers; development of audio guides, integration of the Trials into school curricula; and the development of Trails-related events and programs.”

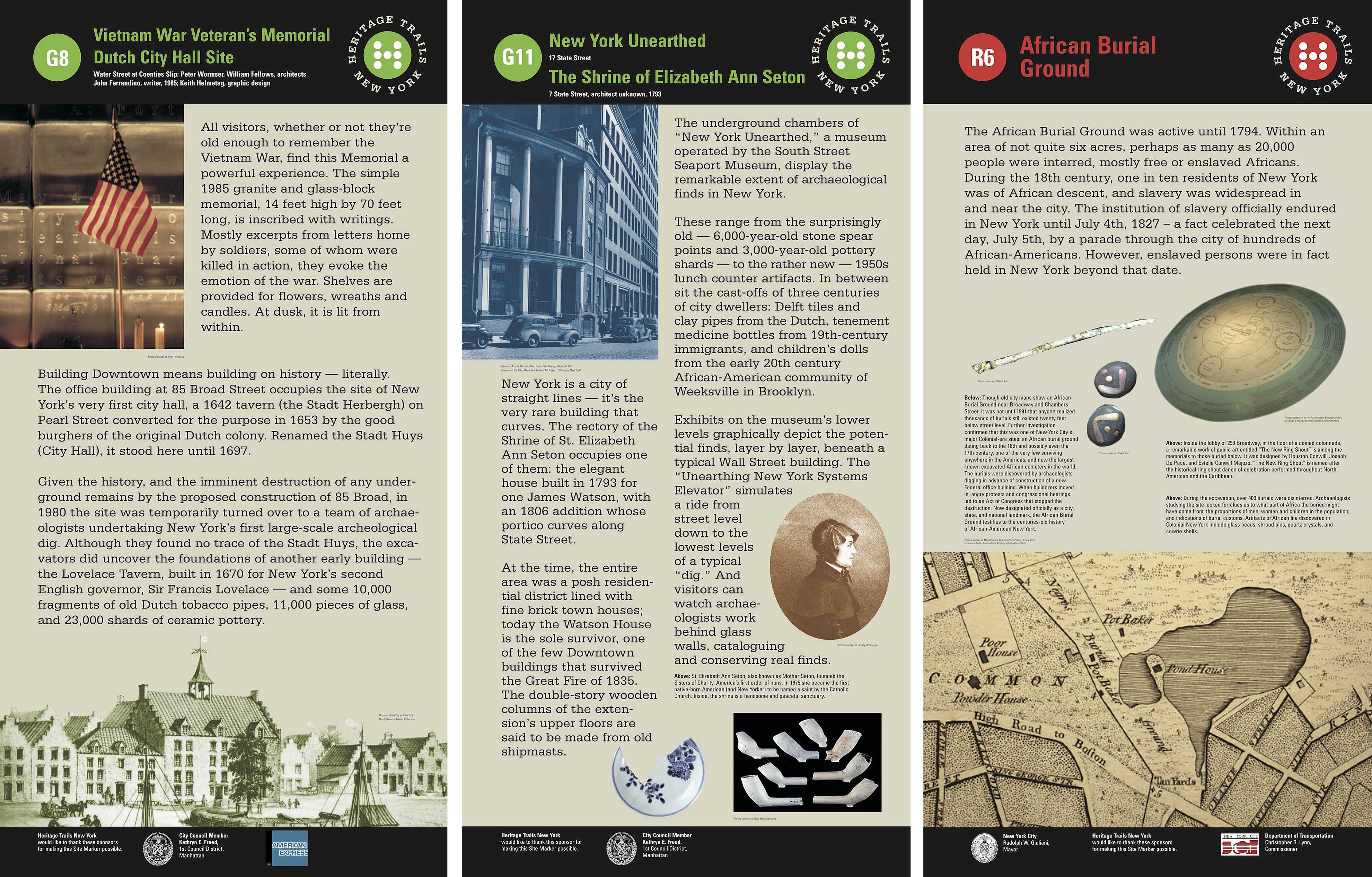

Another theme taken up in several markers was the idea of sites beneath the streets – the findings of digs in the relatively new field of urban archeology. Several excavations for large towers downtown in the late 1970s and 1980s had triggered an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) that resulted in discoveries of remnants of the colonial city. The plaza of 85 Broad Street, a “privately-owned public space” (POPS) created under zoning-resolution rules, contained interpretive displays under glass of a cistern and foundations of the 1650 Lovelace Tavern. (G8) At 17 State Street, in front of a 1988 skyscraper designed by Emery Roth and Sons, a marker called attention to the free, below-ground public gallery “New York Unearthed” that featured a lab where archeologists cataloged and conserved artifacts. (G11) Another planned panel forecast the future site of a memorial honoring the site of the African Burial Ground, which had been designated a National Historic Landmark in 1993, but was still an excavation site in the Nineties. (R6) Recalling this effort to draw attention to the evidence of the colonial past, Tony Robins noted: “We didn’t have this in New York. It was new: the idea that New York was old enough to have an archeology was a big change in perspective.”

A team was assembled to create the text and design of the panels. The work would consume more than a year, through the remainder of 1995 and all of 1996. Tony Robins, who had been hired to write the text for the launch guidebook continued as the chief writer. An architectural historian by training, Robins worked in the research department of the Landmarks Preservation Commission, where many of his assignments focused on lower Manhattan. The HTNY job was freelance work, as was his writing in the same and following years for the Downtown Alliance, for which he authored the brochures created for the series of BID-sponsored “Downtown Open House” events designed to promote access and appreciation for the area’s historic architecture. Nadine knew Tony from her time at working at the LPC as the assistant to the then Chair Laurie Beckelman. There was also a photo-researcher on the team from a company, Carousel, who found appropriate images and procured rights.

One of the signal accomplishments of HTNY was to create a system of wayfinding in lower Manhattan that served both tourists and locals. As HTNY regularly noted in the promotion of their project, New Yorkers were often as confused as tourists by the district’s maze of curving streets, as well as unaware of its rich history. As Lex Lalli wrote in her essay on the work of HTNY:

How do we assess the success, failure, and significance of Heritage Trails? By its own broadest ambitions, it fell short of its goal of becoming New York’s Freedom Trail – a non-profit educational institution that served tourists and locals alike, teaching American history on site in the streets. Failing to establish a Heritage Hub, a permanent, street-level center with an information counter, gallery, and education space, was a disappointment. In New York, real estate rules, and a central location on Wall Street or Broadway might well have made the difference in creating stability for an institution embedded in the heart of the historic core, much the way that the Chicago Architecture Foundation has found a long-term home on Michigan Avenue in the Loop. But the price tag of a permanent home was prohibitive.

Heritage Trails map, 1998.

A broader goal of Heritage Trails – to establish a substantial Visitors’ Hub for tourist information, interactive displays, guided tours, and other facilities in a landmark building on or near Wall Street – was not realized. Two temporary kiosks were installed: one in Federal Hall National Memorial and another in a small area on the 110th floor Observation Deck of Tower One of the World Trade Center, destroyed on September 11, 2001. Today, only 22 of the original cast-iron stanchions survive on the streets, and many have been re-positioned or doubled-up in content.

Now maintained by the Downtown Alliance, the remaining markers today carry the banner “Exploring Lower Manhattan.” Much of the content of the original markers has been included on the current ones, although the layout has typically been changed and the background color is now black. The maps, of course, have been updated post 9/11, but even by 2000, when the Alliance took over HTNY, the maps were redrawn and rebranded. Not a single Van Dam Heritage Trails map exists today on a marker, including the only surviving beige-backed panel, the World Trade Center site marker, which has been incorporated into the installation at the 9/11 Memorial and Museum.

Heritage Trails Panels in situ

LEARN HOW WE RECONSTRUCTED THE LOST PANELS

CLICK ON THE MAP TO LAUNCH THE DIGITAL HERITAGE TRAILS, 1997/ 2017

Richard Kaplan, 1995

From the

beginning, Richard Kaplan’s idea of Heritage Trails was rooted in a much larger

effort to address the many contemporary problems of lower Manhattan, which was

still suffering the effects of the 1987 stock market crash, the

savings-and-loan crisis, and a recession in real estate markets that produced

in 1994, a vacancy rate above 30 percent, with 25 million square feet of office

space unrented. As summarized in a memo for Robert Douglass, the Chairman of

the Downtown-Lower Manhattan Association (DMLA):

“Of special concern to us is the

growing problem within lower Manhattan of an increasing availability of vacant

commercial space caused by the recent real estate slump, a changing workplace,

and the inappropriateness of many of the older buildings to adequately be

up-graded for adaptive re-use for modern purposes.”

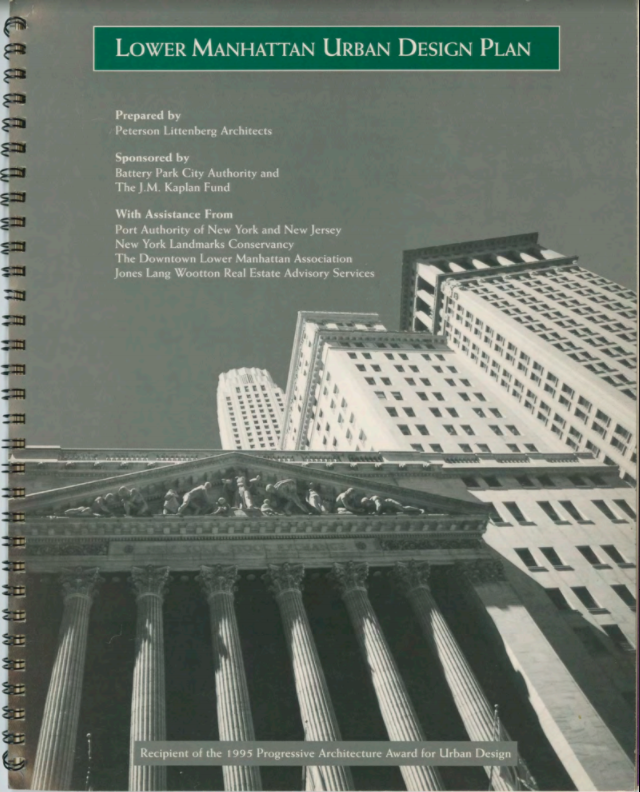

Lower Manhattan Urban Design Plan, 1995

Revitalizing, indeed reinventing Downtown was a big agenda, and Richard Kaplan was by no means the only one focusing on the problem. The Dinkins Administration and its Department of City Planning in 1993 had issued its Plan for Lower Manhattan, and in 1994, the new Giuliani Administration and its Chairman of the Planning Commission Joseph Rose, advanced a package of economic and regulatory incentives that encouraged reinvestments in older buildings. Other city agencies, such as the New York City Economic Development Corporation (EDC) and New York State entities such as the Port Authority and the Battery Park City Authority (BPCA), as well as many professional and civic groups, including the Regional Plan Association and the Landmarks Conservancy, trained attention on transforming the district.

One study that was funded and by the BPCA and also received support from the J.M. Kaplan Fund was Peterson Littenberg Architects’ “Lower Manhattan Urban Design Plan,” which “sought to promote the economic development of Downtown through design improvements to the urban fabric.”

The plan engaged the advice of many stakeholders and was presented at a series of public hearings at the New School in August 1994.

By far the dominant organization in the district, though, was the Downtown-Lower Manhattan Association. Founded in 1958 by David Rockefeller, President of Chase Manhattan Bank, which was then erecting its new skyscraper headquarters 1 Chase Manhattan Plaza, the DLMA represented the voice and the muscle of the business community. Its website today describes its historical role as “a powerful networking platform for senior corporate and non-profit executives, as well as a public policy forum and effective advocate for Lower Manhattan.” In 1994, the Chairman of the DLMA was Robert Douglass, who during his long career had been a right-hand man to both Governor Nelson Rockefeller, serving as his Counsel and Secretary during the late 1960s and early 1970s, and to David Rockefeller, serving as vice chairman of Chase. In 1995, Douglass also became the first chairman of the new Business Improvement District (BID), the Alliance for Downtown New York. The BID, although in fact a creation of the DLMA, subsumed the older organization within its structure.

The Alliance for Downtown New York – today known as the Downtown Alliance – tapped as its first President Carl Weisbrod, who came to the BID from a long career in government positions, including, just before, the first president of the EDC. Funded by a small tax assessment on building owners, the operations of the BID were directed at “the maintenance, improvement, and promotion of their commercial district.” Unlike the corporate base of support of the DLMA, the BID’s programs and services are funded by a special assessment billed to property owners within a district. In the years after its establishment in 1995, the Alliance became the most active force in the area’s efforts at revitalization.

In 1994, though, it was the DLMA that had the wherewithal to promote and execute plans, and as a philanthropist, Richard Kaplan had easy access to the leadership of the DLMA. In a July 19, 1994 memo to Robert Douglass, Kaplan summarized the steps that had been discussed with a DLMA committee in the previous weeks that the J.M.Kaplan Fund proposed to undertake to revive and expand the city’s 1976 Bi-Centennial Heritage Trail as a new and positive step toward a revitalized lower Manhattan. The memo made clear that the motivation for the project was “to stem the pernicious perception of the district's downward spiral” and that the new Heritage Trail was conceived as a doable, short-term Special Project “that can be immediately started and soon completed to effectively demonstrate that there are indeed real changes for the better underway in Downtown Manhattan.”

This strategy that had taken shape over June and July, and especially after Richard Kaplan hired Nadine Peyser to work full time as the project director of what was still then called the “Downtown Lower Manhattan Project.” Peyser had just graduated from Columbia University’s Graduate School of Architecture, Planning & Preservation with a Masters in Urban Planning. Her thesis on the subject of converting older office buildings to residential use was a perfect fit for some of the goals that had earlier been a part of the studies of Kwartler’s Urban Simulation Lab studies. A memo drafted by Richard for approval by the trustees of the Fund outlined the objective of the project they would fund.

After discussion with the Downtown-Lower Manhattan Association (DLMA), we determined that first among these Special Projects to be addressed would be the re-vitalization of the Heritage Trail, a wonderful project that was created in concert with the Bi-Centennial celebration in the City over 20 years ago, but which has now fallen into a kind of urban oblivion.

Library of Congress

The memo continued in a section on the “J.M. Kaplan Fund Efforts to Date”:

As a first task in the planning process for the revived Heritage Trail, we are developing ideas for a new unifying theme and/or mission statement. We believe that in addition to capturing the "heritage" of Downtown Manhattan, a new "spin" might be appropriate to up-grade the Trail to better the new efforts for evolutionary change and growth in the District that is the real underlying concern.

We are looking at the possibilities to expand, upgrade and revitalize the historic trail. In an effort to make the trail active and vital once again, we have decided to consider an expansion and reorganization of trail markers to include themes ranging from archeology to architecture, from Indian walking paths to African burial grounds, from historical financial institutions to the Institution of Capitalism, from Government patrimony to individualist entrepreneurship and International Trade.

By mid-July, the Heritage Trail project was defined, if not yet definitively named. The July 19, 1994 memo summarized the many actions already taken, which included: adding sites; holding meetings with civic organizations and government agencies; preliminary mapping of the extended trail; conversations with designers; and meeting with the Art Commission.

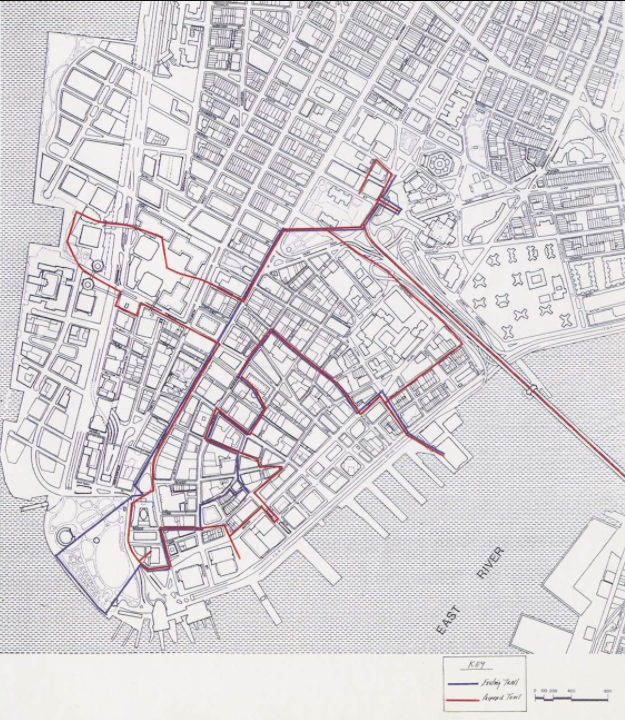

Nadine Peyser 1994 map

Nadine Peyser had been busy rethinking the route of the trail, and another memo of July 19 presented a simple outline of the original 17 Bi-Centennial sites and 13 proposed additions. (Link to document list). The new sites included a swing past the site of the future memorial of the African Burial Ground – then just a fenced-in lot with an excavation in progress – and a new loop to the west that took in the World Trade Center and a bit of the World Financial Center and it's marina. She advised against the original long walk to the waterfront in Battery Park, which she lamented was “shabby”(?). She prepared a map that traced the new route in red, in contrast to the original trail in blue. Her original sketch is seen on the left.

When and How Did Heritage Trails Take Shape?

A big step in materializing the concept of the new Heritage Trail was to hire a graphic designer. Richard reached out to his friend and former Harvard GSD classmate Ivan Chermayeff, a founding partner of the firm Chermayeff & Geismar. They met sometime before July 7, when Chermayeff sent a a one-page letter that summarized their discussion and made a proposal to create “a notebook of ideas to reach out graphically” to the broad range of tourists, workers, and residents. He proposed that by starting in August, their office could complete a study by mid-October, “complete enough to present to key individuals and organizations involved with Lower Manhattan.” The cost “would not exceed $30,000 plus an additional $5,000 allowance for typesetting, photography and other out-of-pocket expenses.” (View the 7-7-94 letter here)

Creating a graphic identity for Heritage Trails New York was a design problem that went beyond signage, a map, and wayfinding: it was creating a “brand” that grabbed attention and made the trail coherent. In the months that followed, Kaplan and Peyser worked with the Chermayeff & Geismar designers, and especially Keith Helmetag, to develop the concepts and graphic identity of the new Heritage Trail – which early on (from date?) became Heritage Trails, plural: four separate trails – Green, Blue, Red, and Yellow – that looped in four directions from a central Visitors’ Center hub on Wall Street.

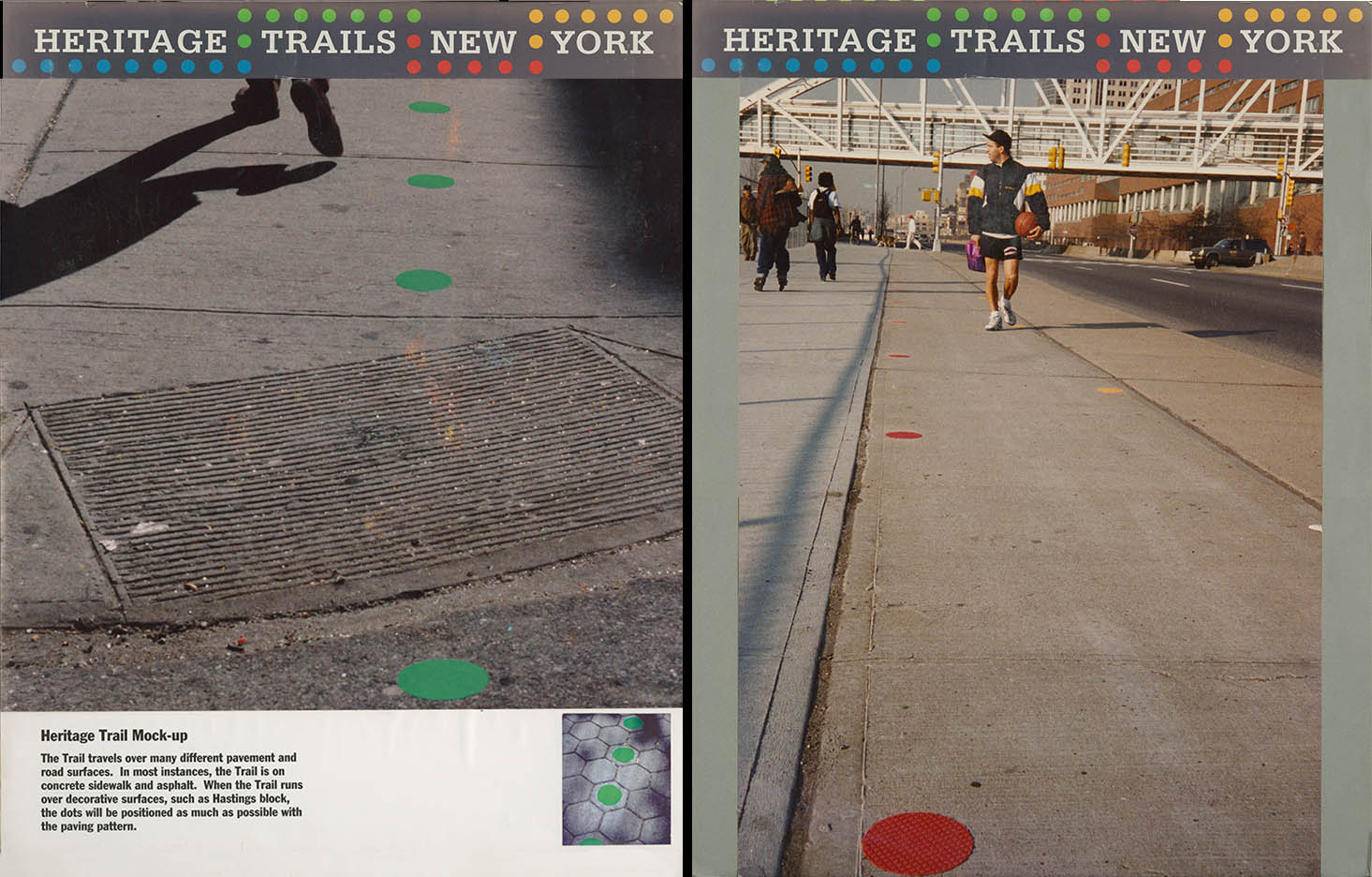

The logo of Heritage Trails New York – a path of colored dots winding below and above white capital letters on a black background – was arrived at fairly quickly. This banner, with or without a black background, was used for the project’s graphic identity for stationery, tee shirts, caps, and the like, as well as, in the first version of the top banner of the site markers (with some adjustments in the position of the colors). As executed in 1997, the final design for the site markers, however, used a variant of the logo as a single colored dot, with an “H” made up of smaller white dots.

LEARN MORE ABOUT THE BRANDING DESIGN

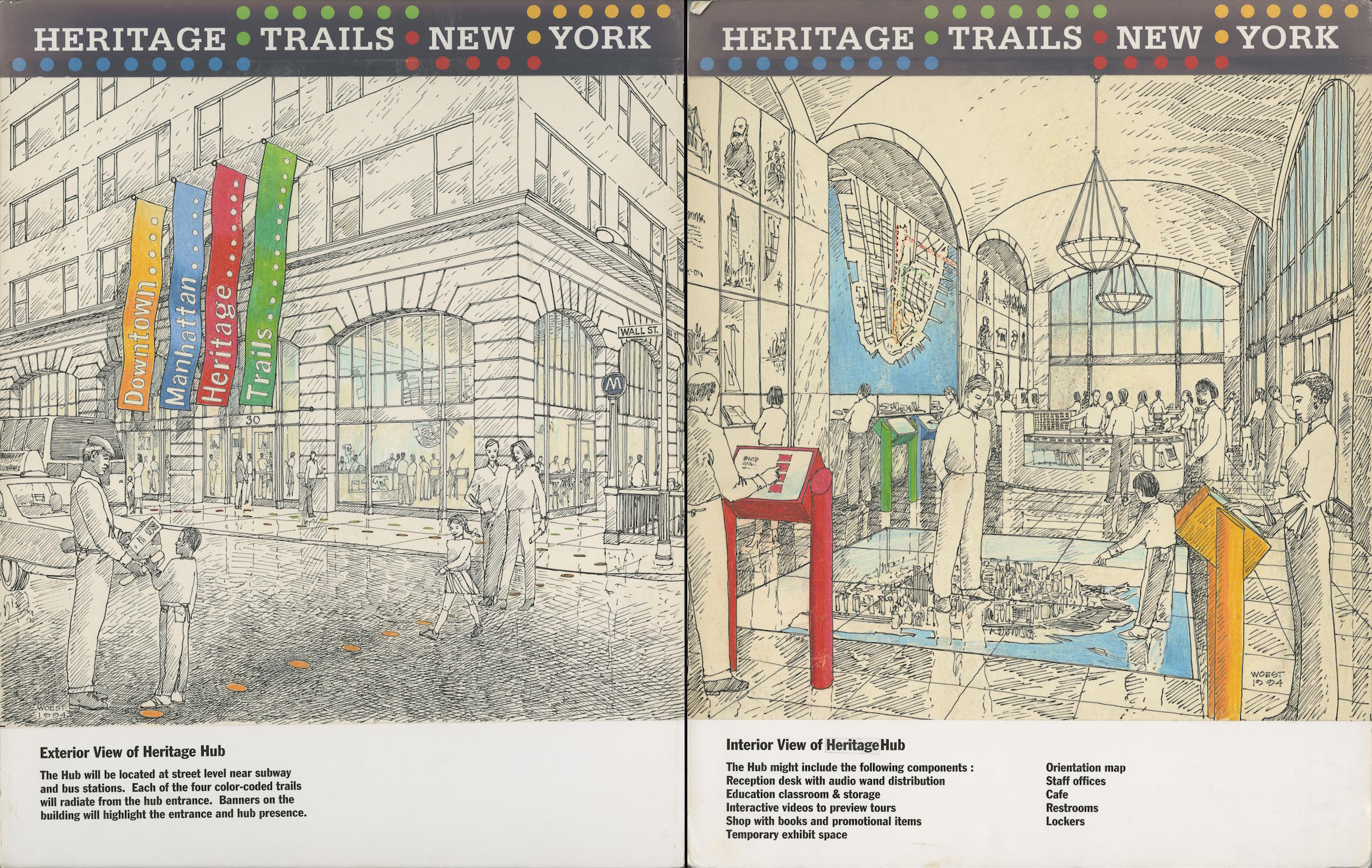

Helmetag’s team also created a series of eleven storyboards that survived in the Richard Kaplan Papers and are now at The Skyscraper Museum. Made as visual aids and well-worn from dozens of presentations to diverse stakeholders, from Community Boards to David Rockefeller, these boards offer a revealing picture of the key concepts of the Heritage Trails project as it evolved. In their assigned order and imagery, the boards summarized the key concepts of the project: 1) a continuous, visible “trail of discovery,” marked on the sidewalk with colored dots, which led tourists past a series of large historical markers placed at key sites, including the 17 from the 1976 Heritage Trail; and 2) a Visitors Center Hub in a central location near Wall and Broad streets that would serve as a place for information, maps, tours, and a small gallery.

The colored dots, keyed to the respective trail, connected to the idea of a physical trail that Kaplan and Peyser felt was part of the reason for the success of Boston’s Freedom Trail, which wound a continuous line of brick and stone pavers to connect the sites. The Hansel-and-Gretel approach of spaced dots – to be spaced about ten feet apart – was simply a practical solution to the impossibility of digging up miles the sidewalks to of lower Manhattan. The dots were illustrated in photomontage on two presentation boards. A durable material was identified, a Scotchbrand product with a strong adhesive backing, that came in bright colors and could weather harsh street conditions. Another board displayed full-scale samples.

Caption

The storyboards also included a map that for the first time represented four trails, looping from a central hub around Wall and Broad streets and Broadway. (Exactly when and how the idea of four trails took shape is unclear. We need to ask Nadine and Keith.) There were three boards with this early version of the map that was made by Helmetag’s team. The first two label the loop to west side through the World Trade Center and World Financial Center the “Yellow Trail,” while an update to the same map labels that trail “Orange.” Nadine Peyser explained the color was changed for the simple reason that there was no yellow Scotchbrand.

The same map was used in a storyboard showing a mockup of the brochure that was eventually produced, with some adjustments, for the June 1995 public launch of Heritage Trails. The cover featured a view of the skyscraper canyon of Wall Street to Trinity Church, and short blurbs on individual sites were illustrated with a small image or “icon” in Heritage Trails terminology. The brochure was intended to fill the gap in delivering the historical content to trail trackers until the site markers were installed – a process which would take the next two years.

Caption

When an expanded brochure was in fact produced for the June 1995 launch, the map it featured was one designed by Stephan Van Dam, a commercial cartographer whose New York-based company created and published tourist guides and maps for a long list of cities. Van Dam’s map showed the buildings on all blocks, not just the streets and blocks as a flat image. Van Dam described his work as a “3-D map” that employed a “sheared 4-point perspective that would let users see all the buildings and the historic trails at the foot of the canyon.” The Van Dam map was illustrated on one of the later storyboards (identified by their black gatorboard backgrounds), which also presented the revised logo for the site markers, the colored dot with the “H” in small white circles.

SEE MORE ABOUT THE VAN DAM MAP HERE

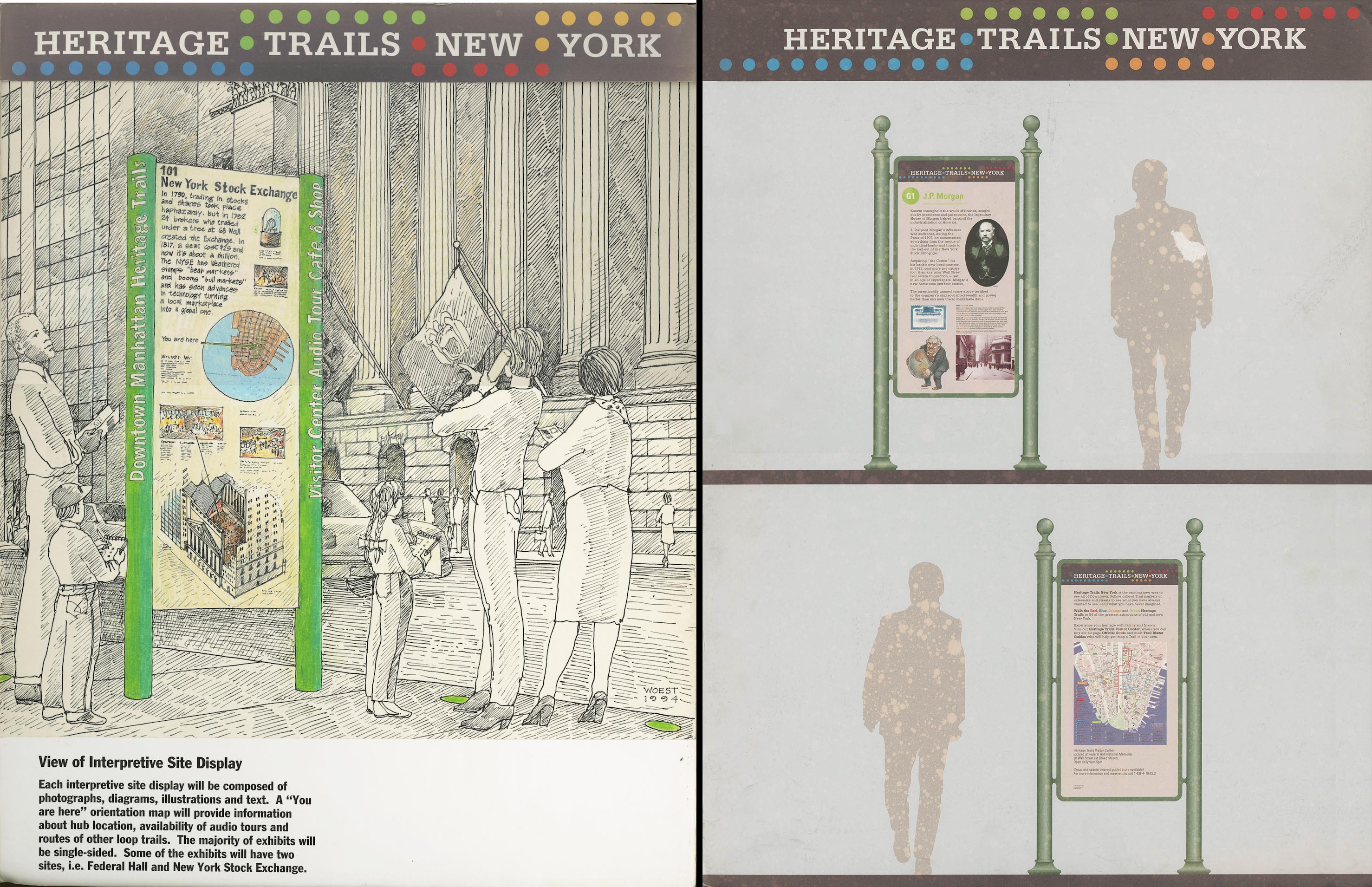

Three of the storyboards featured illustrations in ink and watercolor by the freelance artist Kevin Woest, who was commissioned by Chermayeff & Geismar to create a lively visualization of the future visitors center, called the “Heritage Hub” in exterior and interior views. The street view showed a corner building with large windows, bedecked in four colorful flag banners bearing the words “Downtown Manhattan Heritage Trails.” The caption read: “The Hub will be located at street level near subway and bus stations. Each of the four color-coded trails will radiate from the hub entrance.” The interior view showed a large vaulted space with tourists and happy families engaged with interactive displays and examining a large, detailed model of lower Manhattan beneath a glass floor. The illustration’s caption described an ambitious program for the Hub that “might include”: a reception desk with audio wand distribution; education classroom & storage; interactive videos to preview tours; a shop with books and promotional items; a temporary exhibit space; an orientation map; staff offices; a café, restrooms, and lockers. Woest also drew a sample site marker for the Green Trail that was sited across Broad Street from the New York Stock Exchange. (Notably, the artist showed a couple of automobiles on the street in the area that has since become a pedestrian zone, if only for security reasons, rather than urban design goals.)

Artist renderings of panels

The marker for the Green Trail was a contemporary design of simple vertical posts about 7 feet high that held a panel for graphics and text slotted directly into the columns. The layout of the text and the multiple graphics seem to have been modeled directly on the British DK Eyewitness Guide: New York City, which Nadine Peyser cited as a favored model. The description of the marker storyboard carried the caption:

Each interpretive site display will be composed of photographs, diagrams, illustrations and text. A “You are here” orientation map will provide information about hub location, availability of audio tours and routes of other loop trails. The majority of exhibits will be single-sided. Some of the exhibits will have two sites, i.e. Federal Hall and New York Stock Exchange.

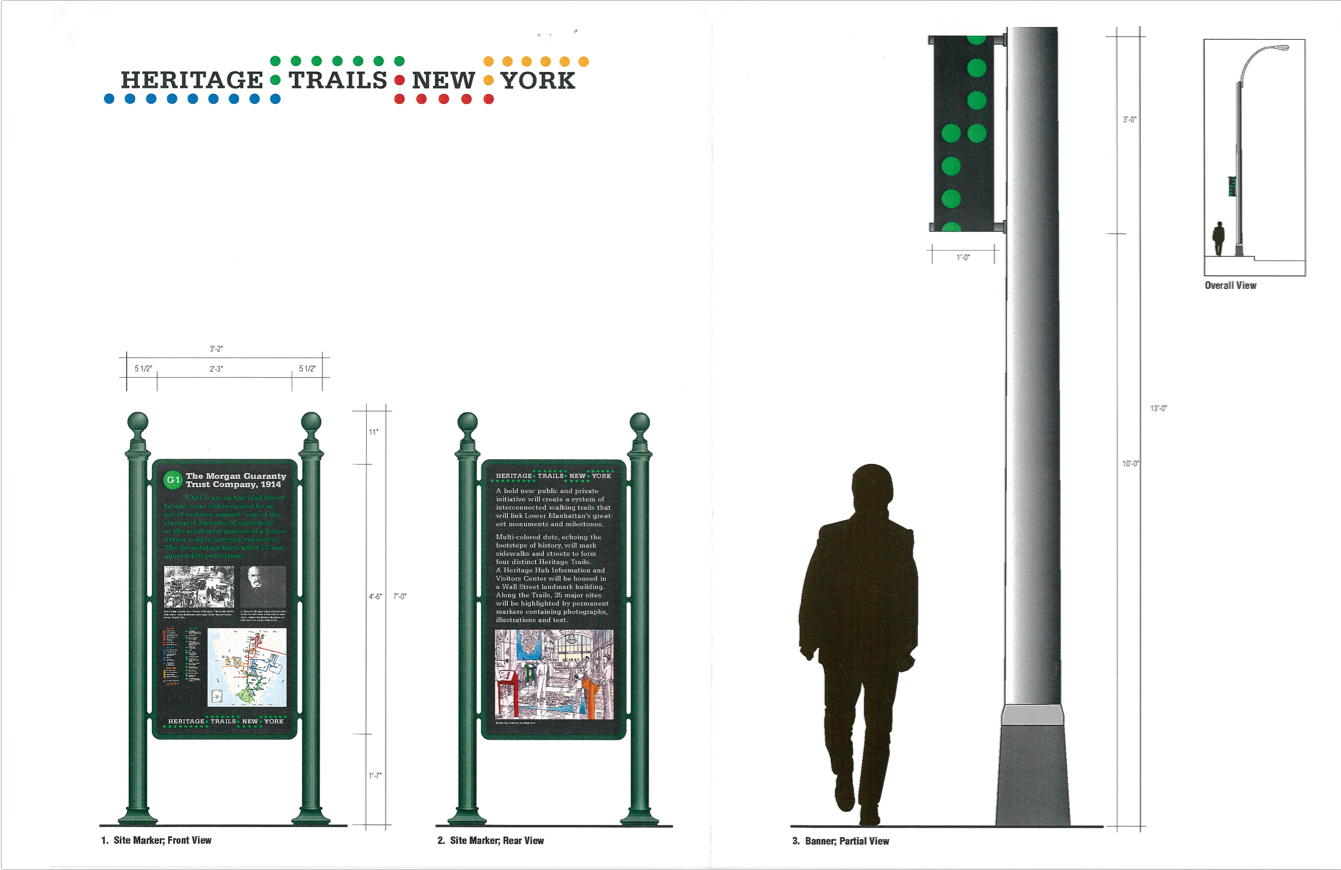

Illustration of final site marker

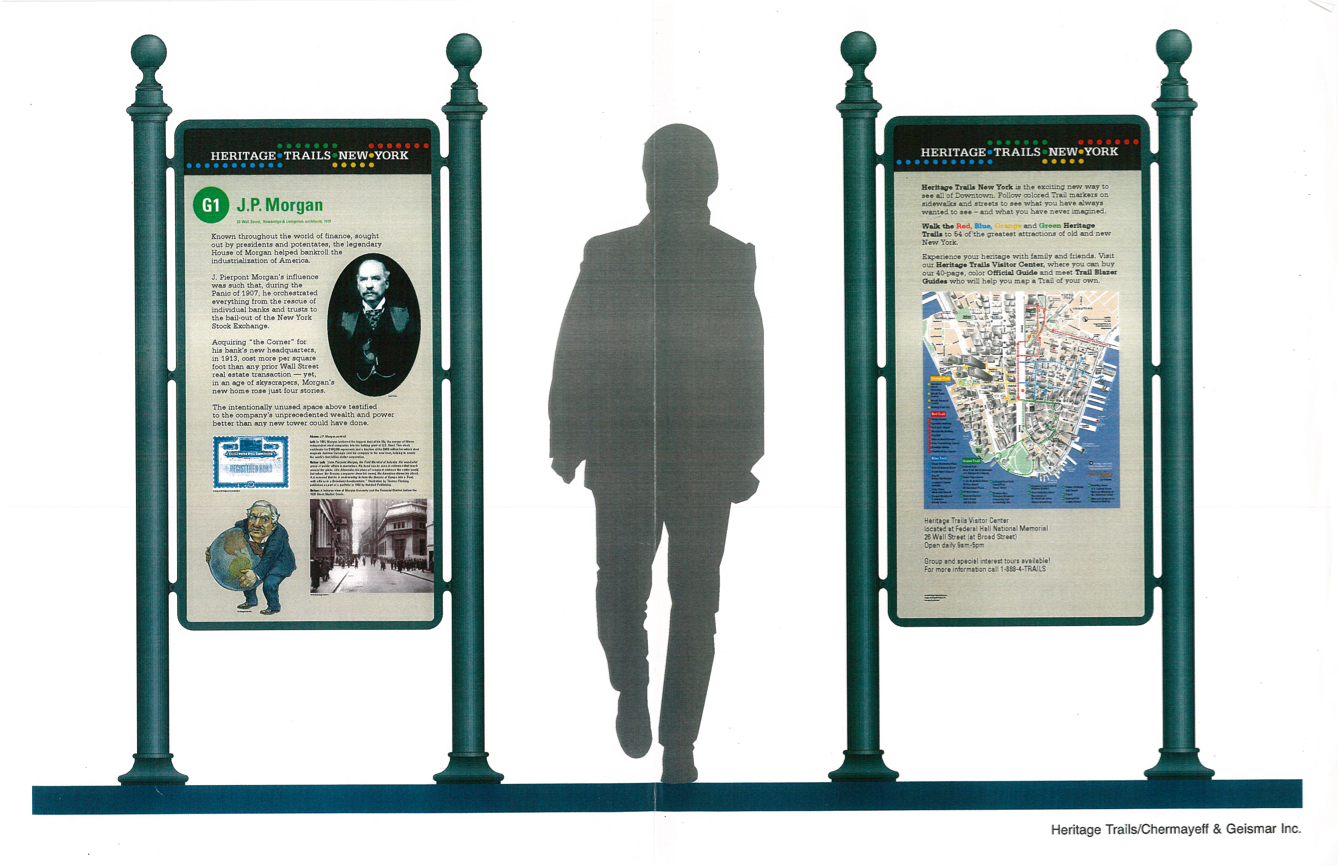

The design of the site markers were later changed to a more traditional, historical model of cast-iron columns, painted green, surmounted by round ball that held a frame of the same material that held the graphic panel. The panel was smaller overall than the more monumental first version, as the figure in the storyboard that illustrated the revised design made clear. Keith Helmetag was the source of this marker, which was modeled on an actual nineteenth-century stanchion that he had discovered in an old photograph of the Financial District. His research unearthed that the original manufacturer still had molds of the originals, so the forms could be replicated in cast iron. That connection to the past was quickly embraced by the project and became the consensus design moving forward.

The set of presentation boards prepared by Helmetag’s team, which effectively summarized the basic features and proposed designs for the four trails, the visitors Hub, and the site markers were completed by the “mid-October” target mentioned in the Chermayeff letter of July 7. Over the fall and winter of 1994-95, they were indeed used dozens of times to present the project “to key individuals and organizations involved with Lower Manhattan.” They also became the basis for the submission to the NYC Art Commission in April 1995.

VIEW THE COMPLETE SET OF STORY BOARDS HERE

Mission Statement: “Downtown’s great history and future promise”

In April 1995, the Department of Parks on behalf of Heritage Trails New York submitted a proposal to the Art Commission to create a “system of four interconnected walking trails” around Lower Manhattan. The Art Commission (now the Public Design Commission) oversees design review over all City-owned property. The proposal required approval from the Commission in order to construct three main parts of the trails – informative site markers; a wayfinding system of dots to be installed on the sidewalks, with portions placed on streets; and nylon banners installed on light posts where the trail dots could not be used. Submitted documents included technical specifications, descriptions of the purpose and scope of the project, and photographic documentation of the 31 sites where the new markers would be installed.

The materials the team prepared to present to the Commission were a finely honed set of documents that brought together the Chermayeff & Geismar branding, illustrations, and map, as well as an eloquent statement of goals and description of the scope of the project.

In particular, the first section, called "Mission Statement," emphasized that Heritage Trails would serve both the past and the future of Downtown. While celebrating the rich history of the area, it also promised an "economic stimulus for its retail, commercial and residential advantages."

In order to highlight these themes, we have bolded phrases in the paragraphs below in a way they were not in the original document (which can be viewed in its full 22 pages by clicking on the cover at the right, which opens a popup window.)

Downtown Manhattan Heritage Trails is a series of new walking pathways through the streets and canyons of New York. By following colored dots embedded in the sidewalks, visitors can “trace” the monuments of Downtown Manhattan’s rich architectural and cultural heritage. The pathways give New Yorkers, visitors, and students alike the thrill of discovering Downtown’s great history and future promise.

From immigrants to industrialists; from Wall Street to World Trade Center; from Seaport to Civic Center; the dotted pathways that comprise Downtown Heritage Trails symbolize the footprints of yesterday’s accomplishments and the heartbeats of tomorrow’s enterprise.

By linking Downtown’s greatest milestones and monuments, Downtown Heritage Trails will help increase public awareness of the wonders of Wall Street and its surrounding environment, providing economic stimulus for its retail, commercial and residential advantages.

The Downtown Manhattan Heritage Trails Hub will be sited at the intersection of the four “trail” loops, and will be housed in a Wall Street landmark building. The Heritage Trails Hub will be the center of a pathway system, providing visitors with exhibits, information, and audio-video communication equipment to more fully enjoy participating in Downtown Manhattan’s great and future heritage.

Downtown Manhattan Heritage Trails will be sponsored by major institutions, organizations, governments and private individuals in Downtown Manhattan: The Center of The City and The Heart of the Global Economy.” (Art Commission Exhibition Files 5789 C)

Caption

The front side of the panel will include a Site code number, a brief description of the site and historic or contemporary photographs, illustrations and captions. An inset map will provide an overview of the Heritage Trails system, as well as announce “You are Here.” The project logotype will be discreetly placed at the bottom. Colored lettering and photographs will be placed against a black background.

The back side of the panel will include a narrative about the Heritage Trails project and photographs of the visitors center hub.

Heritage Trails asked for a two-year demonstration period to evaluate the Trails, after which they would return to the Commission for final approval. The first phase involved the installation of the wayfinding trail dots and a site marker adjacent to the Morgan Guaranty Bank at 23 Wall Street, which replaced an existing Bicentennial Heritage Trail marker. The 6” diameter dots were made of 3M Sta-mark (a type of rubber) in the colors of their respective trails. The trail blaze banners evidently were never installed. The marker mock-up (Art Commission Exhibition Files 5789 C) shows two different colored backgrounds for the marker text, beige and black. Although a black background was used for the Morgan marker, later HTNY markers would have beige backgrounds.

Caption

The proposal was discussed at the May 8, 1995 Art Commission meeting. The Commission gave final approval to the markers, but rejected the wayfinding trail dots. They recommended “that the applicant explore several signage options and develop a system of evaluation for the proposed trial period,” but allowed HTNY to use the dots on an interim basis.

After the initial demonstration period, HTNY appeared again before the Art Commission in 1997, with Commission members still expressing reservations about the material and appearance of the dots. On May 11, 1999 HTNY submitted an updated report to the Art Commission. At that time, Kaplan wrote that 40 markers were in the ground with another two in the works. He stated that they continued to look for “more noble materials for the trail markers,” and after a continued observation period they wanted to meet with the Commission in the fall at which time they would either replace or remove the dots. (Art Commission Exhibition Files 5789 E). The project received final approval on July 12, 1999.

The months between the completion of the Chermayeff & Geismar branding work that defined and visualized the basic features of Heritage Trails – essentially set by October 1994 – the team worked to build a constituency for the project through dozens of meetings and presentations. They added the writer Tony Robins, as well as researchers to find and acquire appropriate illustrations for the brochure, in the short term, and for the development of the site markers.

The only other key documents in the Kaplan papers from this period were the legal papers to establish a 501(c)(3) non-for-profit tax-exempt corporation doing business as Heritage Trails New York. A first set of the papers on January 20, 1995 filed for the name “Heritage City Foundation, Inc.” but a March 21, 1995 resubmitted and was approved for the name “Heritage Trails New York Fund, Inc."

The next major event after the submission to the Art Commission was the public launch of Heritage Trails New York.

Press packet

Press packet

HERITAGE TRAILS NEW YORK

(is) the newest way to see all of Downtown New York. The Trails are a major new

initiative that has created a system of four interconnected walking trails to

physically link 50 of Downtown Manhattan’s greatest sites and attractions.

A Fact Sheet outlined many details of HTNY’s future goals. One key section came in the section titled

“WHY”:

Downtown New York packs an enormous amount into the tiny tip of Manhattan—history,

shipping, banking, monuments, museums, governance, graveyards, markets,

finance, literature and love. Integral to the cultural, preservation and

tourism goals of the ongoing revitalization of Downtown Manhattan, the Heritage

Trails will:

A draft of his speech that survives in his papers conveyed his characteristic ebullience, thanking the numerous government officials and civic leaders assembled and outlining the plans of a broad vision for the future Heritage Trails that would “represent the symbolic footsteps of 400 years of New York’s multi-cultural history” and “re-awaken the public’s awareness of the greatness of Downtown New York.”

Citing the success of Boston’s colonial Freedom Trail – “walked, last year, by more than four million visitors” – Kaplan pointed to the importance of its continuous path of inlaid brick that connected the historic sites on a 3-mile route. Noting lower Manhattan’s own precedent of the 1976 Bicentennial Heritage Trail and its sixteen separate site markers, he pointed out that project “contained no actual trail.” So, he emphasized:

Learning from these past efforts, we celebrate, today, the launch of the new Heritage Trails New York, the private/public, non-profit partnership that has actually put Trails on the Trails.

He was speaking of the colored dots.

Four inter-connected Trails, each created with differently colored circular markers -- (you can call them Downtown Dots) – painted along sidewalks and streets, spring forth from Federal Hall, in approximate one-mile-long loops, stretching to the four corners of Downtown Manhattan and back.

Nadine Peyser and a team from the Department of Transportation had laid down about 2400 of them by the launch. They were six inches in diameter, spaced mostly at ten-feet apart, and in a different color – green, blue, red, and orange –for each trail. The dots made a physical path to follow, but could be engaged at any point on any trail.

The idea of a physical trail was key to the project, but the dots were also especially important in this first phase before the site markers were in place. At this point, visitors had only a map and brochure to guide them to the sites that would be highlighted by the historical panels. Indeed, the site markers would require two more years to install the first thirty.

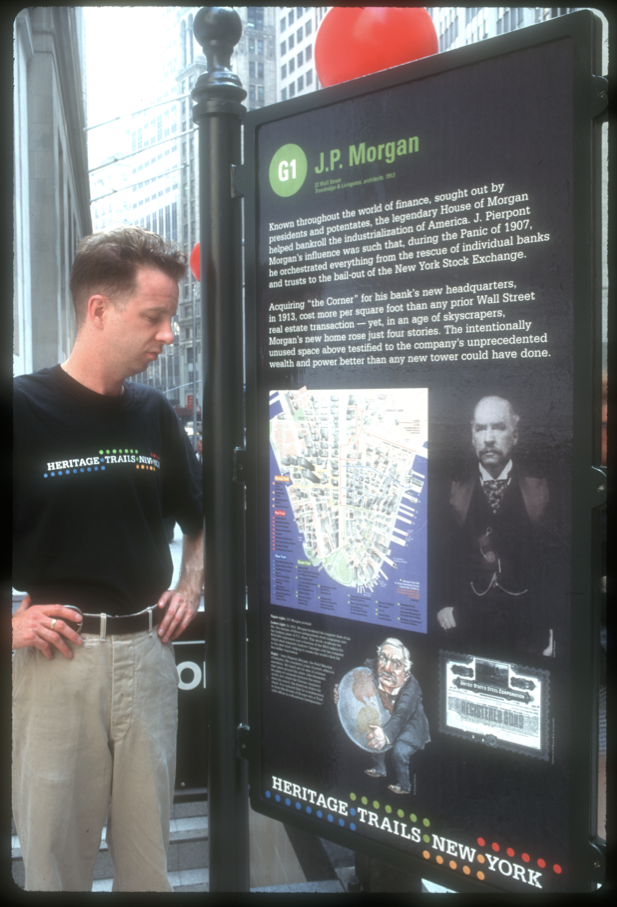

G1 marker outside 23 Wall Street

The prototype of what would ultimately be 40 historical markers was unveiled at the launch. The cast-iron frame was designed (according to the event’s fact sheet) by architect Rolf Ohlhausen, although it was modeled on a late-nineteenth precedent of a New York street sign. The sturdy stanchion carried a panel with images laid out by Chermayeff & Geismar and text crafted by the historian Tony Robins. In the prototype, the map was on the same side as the historical text: this would change in the final panels to the map and other information on the verso. The background color of this first panel was black: in the final panels, it would change to beige. Also, the Heritage Trails logo was at he bottom of the panel.

The interim Heritage Trails Hub and Visitor

Information Center, located at Federal Hall

National Memorial.

The Heritage Hub was a small booth, branded with the Heritage Trails logo and staffed by trained Heritage Trail Blazer Guides, who could “describe the Trails and the great attractions of Downtown, and help users develop their own trails.“ They also sold the 40-page Heritage Trails Guidebook, which included “overlay maps of Downtown streets showing locations of the Trails, site descriptions with anecdotal and little-known facts, full-color photographs, a subway map and a restaurant index,” according to the Fact Sheet. The text for the guidebook had been developed by Tony Robins and served as the basis for the later site markers.

Heritage Trails: Downtown at Your Feet (1995)

The design of the Heritage Trail New York guidebook – subtitled “Downtown at your Feet!” – was created by Chermayeff and Geismar, but it took it cues from the ideas and tastes of Richard Kaplan and Nadine Peyser who favored the model for both the layout and text used in a series called the Eyewitness Guides, which published a New York edition in 1995. Peyser recalled:

“This whole look and feel came from the Eyewitness Guide… a great visitors guide that we looked at as an example of what we thought was very cool. It was the first guide to really use this kind of imagery or icons with text. So we decided for our map brochure that we wanted to create some sort of visual connection or icon so people could correlate between what they were seeing, what they were looking at, something to find.”

This same description of icons and text, by which Peyser meant the frequent use of images that were cropped to an outline of the form, as with the silhouette of St. Paul’s Chapel on the page above, was also employed in the site marker – and, ultimately, markers.

The brochure claimed 50 sites, but some of these were incorporated within the 33 stops marked with dots on the map. In fact, there were two versions of the downtown map included in the brochure: the 3-D one with the buildings depicted in perspectival massing developed by Stephan Van Dam, placed in the front of the booklet, and the flat, figure-ground diagram of streets and blocks by Chermayeff and Geismar in the middle pages. Each version had its virtues. The Van Dam map was favored by Kaplan and Peyser to represent the verticality of downtown’s architectural canyons and offer a sense of place. But the pictorial character of that map meant that the sites could only be designated by the circle of the marker, such as G1, which keyed to the legend and labels at the left edge and bottom of the map. By contrast, the simple, diagrammatic beige blocks and white streets of the Chermayeff and Geismar map allowed for both numbered colored dots and labeled sites.

caption

What existed of Heritage Trails through the first tourist season of summer 1995, and continuing through the first half of 1997, were simply the interim information hubs, the dotted trails, and the 40-page guidebooks for self-guided tours, and a range of organized tours.

Next Steps: Making the Markers

The work of planting forty historical markers on the sidewalks of New York City was no simple matter. As Nadine Peyser recalled, there were 42 steps required to install every marker, even after it was written, designed, and fabricated. The pace of placement was not quick: one new marker was unveiled at City Hall on January 7, 1997. By September 1997, more than two years after the HTNY launch, thirty of the planned forty were installed. The last ten were completed around May 1999.

The common sense of beginning with the 1976 Heritage Trail map with its three-mile route and 15 markers was clear, as was the idea of expanding the number of trails and adding new sites. A loop to the west side of Broadway would lead tourists through the World Trade Center, which had been completed just a few years before the Bicentennial, and to the recreational waterfront of the World Financial Center and Battery Park City, neither of which existed in the 1970s.

The four trails, each about a mile long, now all looped back to Wall Street, either to Federal Hall or Trinity Church. In practice, they could be joined at any point, and trails could easily be switched, following the Van Dam map and brochure as the guide.

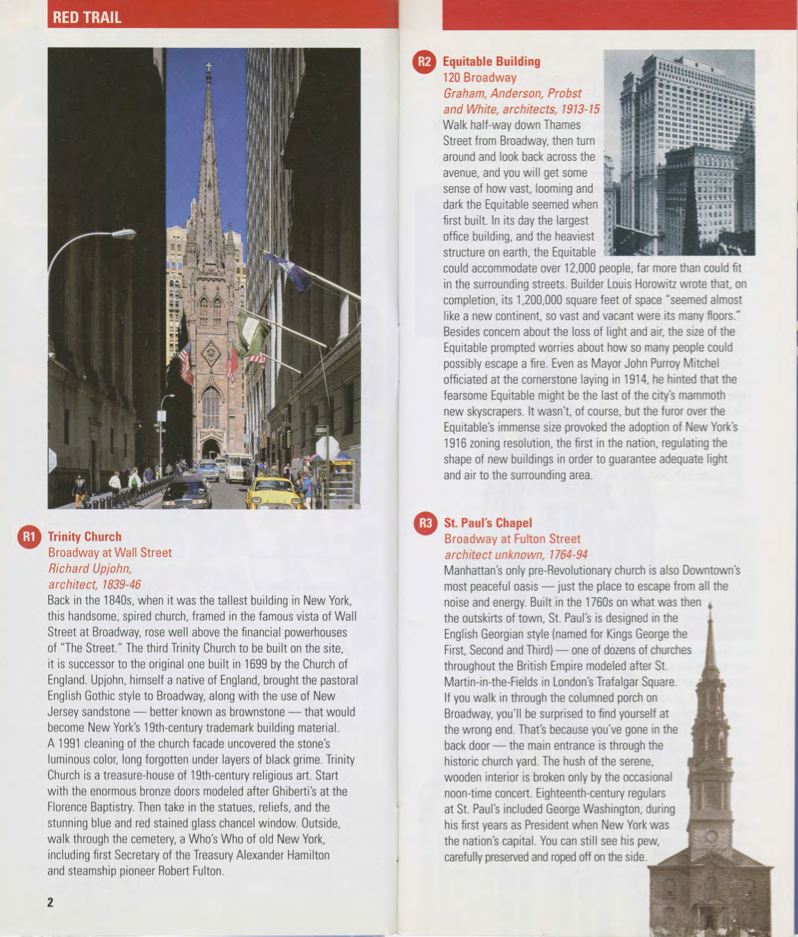

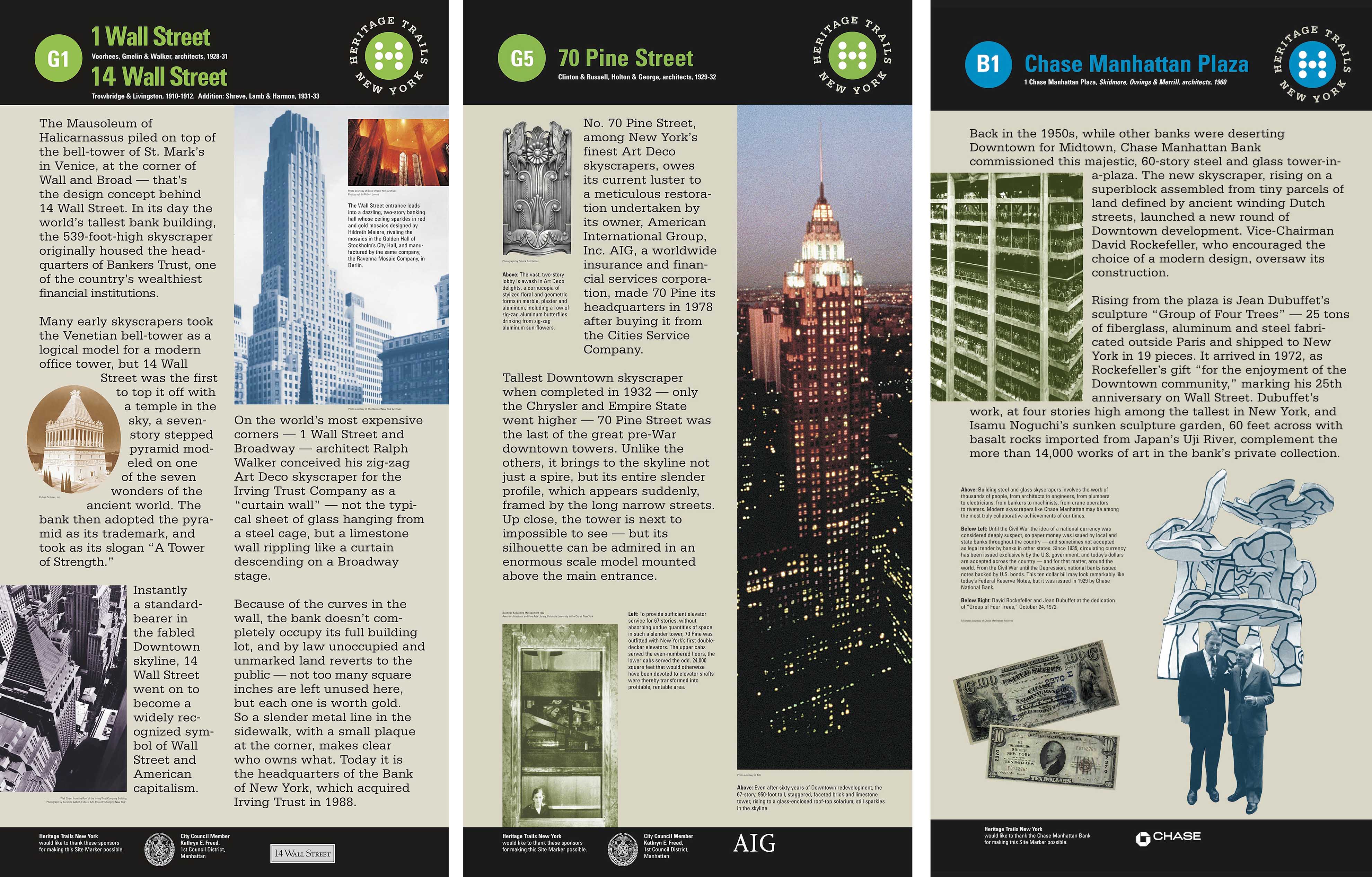

Adding new trails and sites opened up new territories of downtown for tourists and also broadened the buildings and subjects considered “historical.” Skyscrapers – a dozen spanning from the early twentieth century, 1920s Art Deco, classic modern, and just completed– were to be celebrated on new markers. (G1, G3, G4, G5, G11, G16, B1, B7, R2)

Caption

Caption

Richard Kaplan was deeply involved in the creation of the markers, guiding both the topics and tone, as well as working on the final editing. Recalling their ambition to appeal to a broad audience, Nadine Peyser explained:

The text we felt needed to be mainstream. It had to be appealing; it had to be jazzy; it had to tell facts. This was not, obviously, an academic exercise. We were dealing with great minds and great researchers and people who were academics, but we had to get Tony to write with more of a through-line, understanding who his audience was going to be: tourists, visitors. So that’s where the spirit of the text had to… have a certain lightness.

Asked to recall the process of the direction and editing, Tony Robins noted that Nadine “was quite clear on the tone that they wanted… that it was to be bright, not academic. She was particularly interested in a guidebook that had just come out called [Eyewitness Guide].” The entries were to be short, 100 or 125 words, and divided up into sections, sometimes of different sizes, that related to the illustrations. The mix of topics ranged between architecture, national history, but “every site was different." Robins also recalled:

Richard wanted to be sure we got in a lot of American history… “Be sure to tell the story of the original Federal Hall as the nation’s first capital; include an image of Chase Bank-issued currency on the site marker for Chase Manhattan Plaza. On the City Hall marker, tell the story of Lincoln’s funeral cortege and the crowds it attracted. For the Federal Reserve Building, note the presence of the gold vaults in the basement that enabled foreign governments to trade with each other by carting gold blocks from one country’s cage to another’s. At India House: more emphasis on shipping; the inside of India House is full of models & other sailing memorabilia.” A note on one draft of the site marker for the courts district on Foley Square: “Can we get a shot of the court with a movie star on it?”

Peyser also recalled: “Richard edited and edited…. from grammar, syntax all the way through. He was very meticulous."

Caption for 5sy

The Chermayeff & Geismar team, led by Keith Helmetag, was responsible for the design and fabrication of the panels and the cast-iron stanchions. Between the time of the sample marker installed for the launch in front of 23 Wall Street and the remaining 39 markers, a few basics changed. Most notably, the background color shifted from black to beige. The neutral color was perhaps easier to read and to lay out with the range of images, but it also clearly differentiated the black banners at the top and bottom of the panels. These were the zones for the Trail Dot number and the HTNY logo and the area for sponsor credits below.

Caption

While earlier versions of the panels located the HTNY logo of the winding path of colored dots variously on the bottom or top in design drawings, in the final markers, a new, more compact logo occupied the top right corner of every panel. Color-coded by trail, this was a 6-in. diameter circle (the same size and the pavement markers) that featured an “H” composed of small white dots and was surrounded by the words HERITAGE TRAILS NEW YORK in a classic serif font. A certificate of trademark registering this logo, dated February 23, 1999, is included in the HTNY archive papers.

In addition, in most cases, the map moved to the rear of the historical panel (or vice versa, if you think of the map as having the priority of way-finding.) This placement would seem obvious, but in some early panels, notably Bowling Green and Pier A, the maps appeared in a portion of the top of the panel, making the map smaller and, for short people, considerably harder to read.

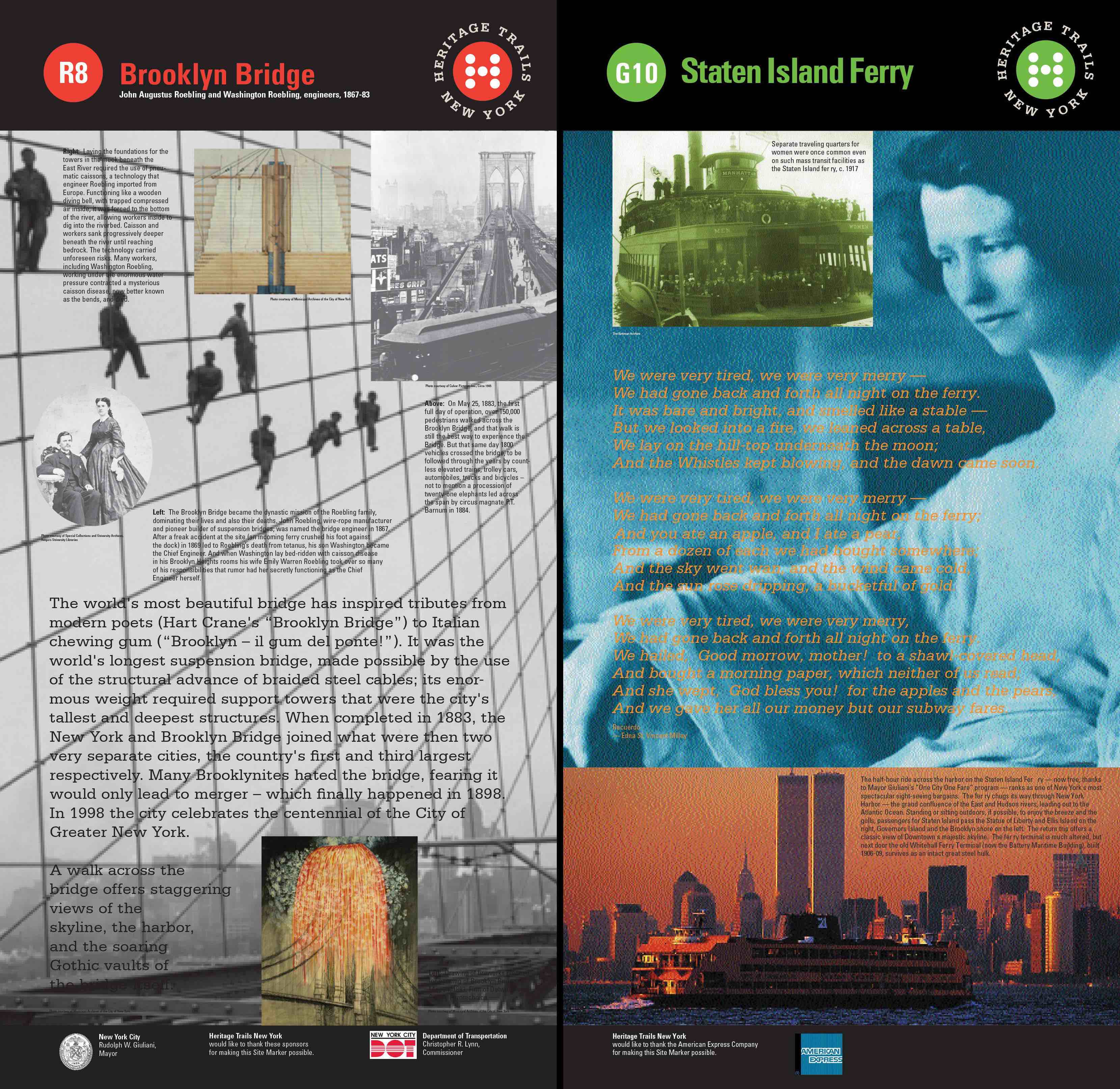

Two panels were substantially different from all the others – Brooklyn Bridge (R8) and the Staten Island Ferry (G10). While Brooklyn Bridge did have a beige background, the whole panel was treated as a single image by the overlay of a famous photograph of the bridge under construction, with seven workers posed on the lattice of cables. The Staten Island Ferry panel was a real oddball: composed of three large images with dominant colors of blue, green, and orange, the longest text was a three-stanza poem by Edna St. Vincent Millay about a couple savoring the night on multiple ferry transits. Asked why that marker broke the convention, Nadine Peyser recalled that there was a lot of competing signage at the location that called for some strong images.

G10 and R8 Panels

The 7-foot tall cast-iron stanchion, or frame, that held the panels was the inspired appropriation of Keith Helmetag, who spotted the structure in an old photograph of a Manhattan street view. Research revealed that the sign posts had been made by Robinson Iron in Birmingham, Alabama, and that the company still had the original molds. Keith recalled that the new design was embraced fairly quickly as an alternative to the first, more modernist version prepared for the Art Commission presentation. Nadine Peyser also noted, “We worked very hard on the site marker design, the cast-iron, wanting to kind of look backwards but forwards, keeping the integrity of the history of downtown.” Although the Art Commission renderings show the frame painted a dark green, all the installed stanchions seem to have been painted black.

The siting and the installation of every marker required many steps. As Peyser explained:

Nadine Peyser explained the intense process of siting, review, and approval necessary to install each marker:

If you were to look across a spreadsheet today – remember we didn’t have the technology that we have today – but to get all the steps, for one site marker from start to finish, 42 very deep steps…

We had DOT [Department of Transportation]. We had to get approval from the Community Board. I guess we had a blanket approval with the Art Commission. The Alliance was very helpful because they obviously had some geographical oversight.… Every building owner had to give permission. So where we could put then in parks or public plazas or find more space around them we did. But at least 42 steps… (Nadine Peyser, April 3, 2017 33:50)

And Keith Helmetag noted:

The real challenge of the job, as Nadine will attest, is you could put a kiosk back where the 1976 ones were pretty much 1 for 1, except the footings were different, so that’s a whole mess. And something has to go, and something has to come in anew. Right, that’s a mess. But the bigger challenge was that they wanted to add to it. The whole thing gets whacky. And then they want to put down 3,000 dots on the street, which you could be put in prison for. So that’s the challenge, and Nadine, to her testament, was the trench worker.

Downtown Express,

Jan 21, 1997

To summarize, the work of creating and installing the forty planned markers consumed four years from the placement of the prototype at Wall and Broad streets in June 1995. The pace started slow, with the one marker at City Hall on January 9, 1997, and another sponsored by Rudin Management at 55 Broad Street, then just refurbished as a “Silicon Alley” incubator, the New York Information Technology Center. Another set were placed by July, and by September, a total of thirty were installed. There were also sidewalk kiosks outside of Trinity Church and Pier A and the Visitors Center in Federal Hall National Memorial.

New sites were added in 1998: the Museum of Jewish Heritage/Wagner Park to the Orange Trail, and William Barthman Jeweler to the Red Trail. In 1999, for reasons that have not been documented, the Equitable Building was switched from the Red Trail to the Blue.

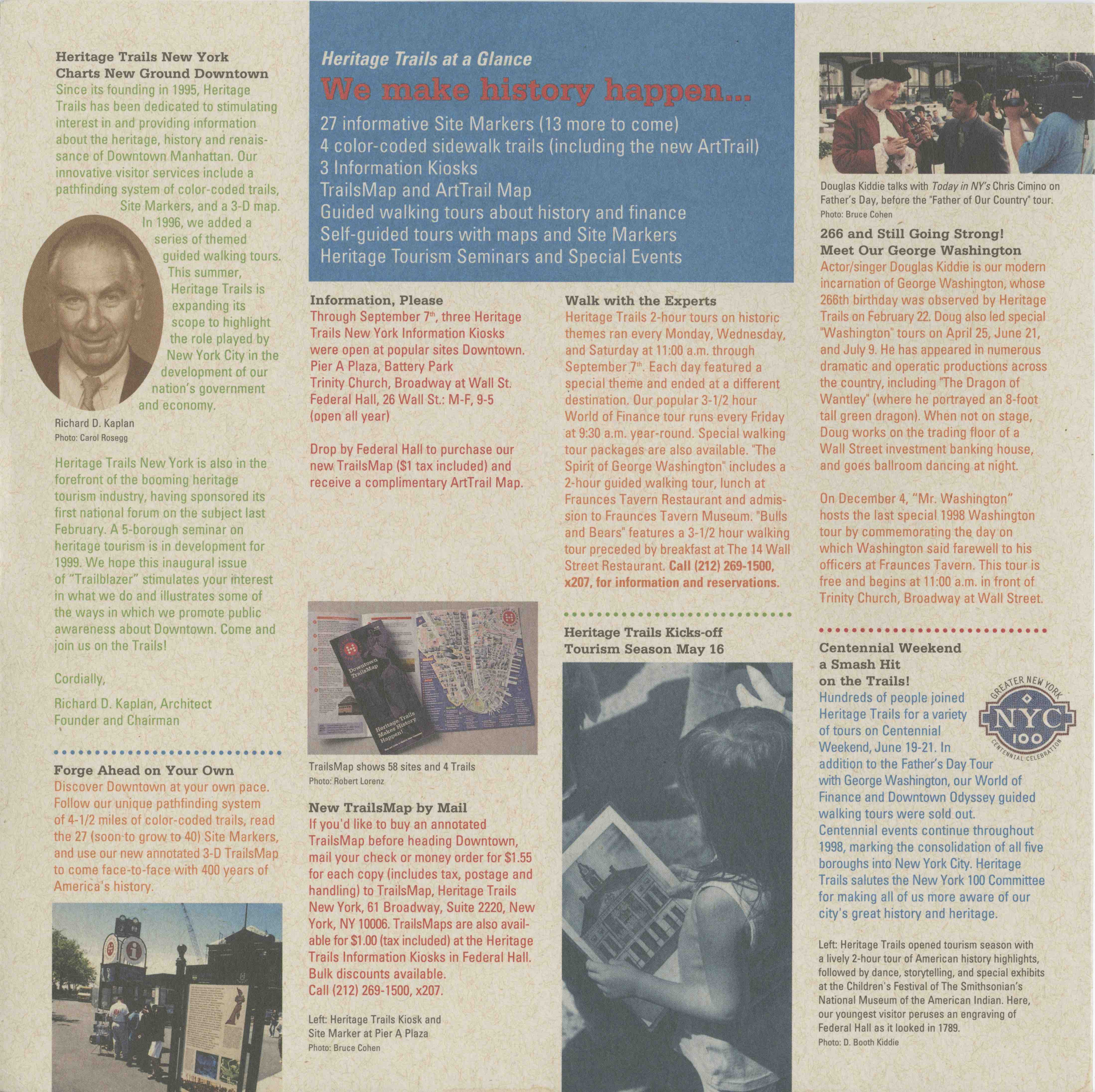

HTNY Newsletter, Vol, 1, Autumn 1998.

A newsletter, designed by Chermayeff & Geismar and published in autumn 1998, highlighted the accomplishments to date: the site markers; the four color-coded trails’ plus a new ArtTrail; the three information kiosks at Pier A Plaza, Battery Park, and Trinity Church; the TrailsMap and ArtTrail map; guided walking tours; self-guided tours; as well as a Heritage Tourism Seminar and Special Events.

By May 1999, Heritage Trails had installed most of the site markers. Alexia Lalli wrote to Deborah Bershad of the Art Commission on May 11, 1999: “We have nearly completed our Site Marker Program – 40 are in the ground and the remaining two are in the works.” (Art Commission Exhibition File 5789 E)

Implementation and expansion of HTNY

The sheer amount of work and the ambitious scope of the HTNY project as they pursued the implementation of the trails markers and the goal of a permanent visitors hub required a considerable amount of administration and fund-raising. In July 1996, Alexia Lalli was hired as the Executive Director of HTNY. Lex, as she was known, brought her experience in marketing and communications to the job. There were both long-range planning and day-to-day details to keep under control and to promote. The HTNY office, now located downtown at 61 Broadway, had to keep track of seven full-time staff members, four to seven consultants, and six paid college interns.

The HNTY non-profit organization had a small working board of eight trustees, led by Richard Kaplan, who included: Laurie Beckelman, former LPC Chair; Adrienne Bernard, Esq.; Rachelle Friedman, downtown booster and co-owner of J&R Music and Computer World; Eliot P. Green, Esq.; Stephen D. Lemson; H. Claude Shostal, President of the RPA; and Carl Weisbrod, head of the Alliance for Downtown.

Tours were a major part of the activities of HTNY in this period. The number of guided tours had grown steadily, from 266 paid tours in 1996 to approximately 3,000 by September 1997. Tour themes in 1997 included: a Pirate’s Day Tour, offered together with New York Waterways; World of Finance; George Washington Walked Here; American Roots in Historic Down Town, about the area’s ethnic heritage, Historic Wall Street: Where the World Makes Money about finance; Downtown’s Skyscraper Canyons about architecture; The New Downtown, about contemporary and future Downtown; and 1624-2001: A Downtown Odyssey, about the history of lower Manhattan.

Paid tours, however, represented a commercial component that diverged from the basic concept of HTNY as a self-guided system with 24/ 7 access. Tours required paid guides, appointment times, marketing, and accounting. They would have been a good complement to the trail maps and markers if the Heritage Hub had been implemented as a visitors and education center, and they worked to build an interim identity for HTNY while the markers were created, but in their commercial aspect, they competed against some existing businesses such as the big operators like Grayline Tours or niche markets like Big Onion Walking Tours. While Chicago can boast of its more than 45-year old Chicago Architecture Foundation, which presents a regular and varied repertoire of tours led by volunteer guides, New York has never had a successful model of non-profit educational tourism.

As Lex Lalli reflected on the role of tours and the necessity of marketing in her essay on the work of HTNY:

General marketing to the local and larger communities and tourism outlets would establish Heritage Trails as a major tourist attraction. To succeed, Heritage Trails had to develop and maintain good relations with all the downtown attractions and institutions. We interacted closely with the Alliance for Downtown, the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council, the New York Convention and Visitors Bureau, Battery Park City Authority, the Battery Park Conservancy, the National Park Service, the South Street Seaport, among others. Various New York City departments – the Department of Transportation, the Landmarks Commission, and the Mayor’s Office among others – were to be informed and made our partners in the endeavor if we were to succeed.

Paying for the markers and expanding the staff and activities of Heritage Trails required fund-raising. As Lex Lalli explained:

While the J.M.Kaplan Fund had been very generous, funds had to be raised to accomplish the goals. It was essential to find and apply to appropriate Foundations, and inform local banks and businesses about our mission and ask for help.

A grant from the Robert Sterling Clark Foundation enabled Heritage Trails to hire a consulting firm that established a firm business foundation for the organization.

A roster of the many corporations, organizations, agencies, and others that donated to Heritage Trails appeared on the back cover of the 1999 Heritage Trails map. They included as Underwriters: The Alliance for Downtown New York; American Express Company; Booth Ferris Foundation; The Chase Manhattan Foundation; City Council Member Kathryn E. Freed; J.P Morgan & Co., Incorporated; The May and Samuel Rudin Foundation; and The Starr Foundation. Benefactor-level support came from: American Stock Exchange; The Bank of New York; Robert Sterling Clark Foundation; The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation; The William and Mary Greve Foundation; The NYC Department of Transportation; and The New York Mercantile Exchange.

More than thirty other businesses, foundations, or government agencies were listed under the Patron, Sponsor, and Friend categories.

Some sponsors, including private, corporate, and government sources, contributed funds for the markers and were noted in the credits at the bottom of specific panels.

One aspect of the broad goals of HTNY proved too costly to implement: the visitors center, originally envisioned as the Heritage Hub and later called the Downtown Tour and Information Center. As Lex Lalli summarized the considerable effort in the years from 1996:

Much research was done and plans developed for the establishment of a Downtown Tour and Information Center. Many locations were proposed, and partners were sought to make this a reality. The American History Workshop presented a concept for the Center. This was an unfinished part of the Heritage Trails efforts. In the long run, several sites, such as Pier A and a partnership with the Museum of the City of New York, which was to move to the Tweed Courthouse, fell through and a suitable site within the range of what Heritage Trails could afford was never found. Richard Kaplan was especially disappointed that this was not accomplished.

Nadine Peyser also noted the difficulties of securing space for a permanent hub: “Richard was always on the real estate hunt, like where else can we locate.” But finding an ideal space that would be a permanent home and education center – beyond the kiosks serving tourists to dispense maps and offer tours – was beyond the budget of the non-profit.

Efforts to create a business model that would generate revenue to sustain the HTNY operations also fell short. Consultants were hired, but the results were disappointing. HTNY initially raised money through grants and individuals, foundations, and corporate sponsorships, but as Peyser noted:

The hope was that there were other revenue-producing elements that we could produce that would help us to put money back into the trails. And there wasn’t. We shot high, hoping we were also going to create something that was technologically advanced, that was modern, to answer your question the sense of the 3D buildings. We were trying to create a trail that was also going to reflect the spirit of New York. The Freedom Trail is really very basic in Boston, but it works. Going back to basics.

…

So we were trying to figure out – why can’t we have every kid in New York walk the historical Bicentennial Tour of New York. We were talking to the Board of Education, we were talking to Gray Line, the gamut.

But Peyser also reflected:

I think there was a naiveté though, in understanding how this needed to be marketed and promoted and trying to build ourselves into the existing tourism network in New York and really thinking about Gray Line Tours and all these walking tours, and Big Onions tours and trying to align ourselves and the trails to maximize visitors and exposure. But we…were definitely hitting grounders, trying to get the trails exposed. We were thinking about multiple languages, we were thinking about acoustic-guide wands, which at the time museums were using for multiple languages, so we were trying to find ways to appeal to a diverse group of visitors, languages, and New Yorkers.

(c) 1999 Van Dam Map

(c) 1999 Van Dam Map

Then, as now, the streets of Downtown below Canal Street retain the elements of the colonial city, and it is difficult to find a destination or even wander without confusion. Although many subway and bus lines serve the area, once you are there, the best way to get around is still to walk, but with no clear east-west corridor or sufficient street information to find your way.

Directional signage was almost non-existent, or at best difficult to interpret. Tourism was pretty much limited to the Statue of Liberty/Ellis Island, the New York Stock Exchange, South Street Seaport, and Windows on the World. Residential buildings were mostly in Battery Park City. Workers poured into the area every morning and exited every night leaving the streets deserted on evenings and weekends.

It is worth emphasizing that during the conceptual stages of Heritage Trails, the Alliance for Downtown New York, founded in January 1995, was brand new. The focus of the Alliance was multifold, but given the context of the persistent real estate recession in the mid-1990s and the exodus of many companies in the financial service industry from the historic core of Wall Street, economic development took immediate precedence. This included boosting both the retail and tourism sectors, but the key long-view agenda was transforming Downtown into a “24/7” neighborhood that included residents and well as workers.

Once the Alliance gained its own branded identity, created by the graphic design firm Pentagram, the BID took over the role of organizing consistent wayfinding signage throughout the district. The specter of “mixed messages” of conflicting maps was a concern: indeed, after the Alliance assumed responsibility for the HTNY project in 2000, the Van Dam map on the stanchions began to be replaced by the Alliance’s 2D map, which featured a different set of attractions and information.

The contractual hand-over to the Alliance on April 7, 2000 in fact prefigured the end of the road for Heritage Trails. By October 30, 2000 HTNY had started to remove the trail dots from the sidewalks and streets of downtown.

The End of the Trails

By the end of 1999 HTNY’s original mission was nearly complete: of the 42 site markers that HTNY had permission from the City to install, 37 were in the ground. The placement of the three markers that had been in City Hall Park – City Hall, the Woolworth Building, and Printers Row – were still in negotiation due to the restoration of the Park. Two markers that were suggested for Cunard/Police Museum and First Synagogue/ French Huguenots were never installed.

With the workload lessened and funding tight, Kaplan, Lalli, and Peyser were, according to a memo to the HTNY board, “no longer intimately involved in a day-to-day manner.” A report to the J. M. Kaplan Fund Inc. summarized the status of the HTNY activities:

In 1999, as HTNY began to scale down its operations, JMK funds again went toward operations which included rent, salaries and benefits, office equipment and supplies, and general office expenses. HTNY moved into more modest quarters and reduced its staff to three people.

The discussion before the respective boards of both HTNY and its principal source of funding, the JM Kaplan Fund, therefore turned to the question: “What is to be the shape of the future for Heritage Trails?”

Earlier that fall, HTNY had begun discussions with the both the Alliance for Downtown and the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council (LMCC) to explore partnerships. For the October 7, 1999 HTNY Board Meeting, Lalli and Peyser reported that the Alliance had taken over the maintenance of the markers, except for those outside their official geographic area due to insurance problems. The Board was also informed that the Alliance had agreed to assume responsibility for much of the remaining assets and programs of Heritage Trails, including the insurance of site markers; offering the “Destination Downtown” tour; distribution of the HTNY “TrailsMap”; and use of Heritage Trails copyrighted map as “THE map for Downtown.”

On January 4, 2000, the Alliance and HTNY signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU). A joint press release issued on April 7, 2000 announced the merger and noted that HTNY had been “instrumental in boosting the Downtown tourist population to 7.2 million visitors annually and increasing Downtown’s hotel occupancy rates by approximately 15 percent.” The statement promised that the merger with the Alliance would make the HTNY project a vital part of a larger Downtown plan:

The marriage of the Downtown Alliance and Heritage Trails combines Downtown’s tourism and initiatives of the Downtown New York Streetscape Plan, which recently received an award for excellence in design by the New York City Art Commission. The historic site markers and revised three-dimensional map will be added components of the Downtown Alliance’s new wayfinding system. Visitors will be provided with attractive, directional signage that will not only guide them from one site to the next, but will also help foster awareness of the area’s historic treasures. The new map will also be produced as a hand-held guide and distributed to 500,000 people.

HTNY and the Alliance held a celebratory dinner on May 2, 2000. In his speech Richard Kaplan identified the key contributors to the project: Nadine Peyser and Lex Lalli; the J. M. Kaplan Fund and particularly his sister Joan K. Davidson and his nephew Peter Davidson; the Heritage Trails Board; the Heritage Trails creative team of designer Keith Helmetag and map-maker Stephan Van Dam; former Deputy Mayor Fran Reiter; Councilmember Kathryn Freed; and Landmarks Chair Jennifer Raab.

From the outset, the fixed idea of Richard Kaplan and Nadine Peyser had been to create physical trails on Downtown’s streets and sidewalks for visitors to follow as paths of discovery. The colored dots were in fact the only trails for the two years before the site markers were installed, and they survived for a couple more years to guide folks from one stanchion to the next. So, the question arises: Were there still Trails without the dots?

During the negotiations with the Alliance to assume the assets of HTNY, the BID made it clear that it was unwilling to maintain, and especially to carry the insurance required for, the Heritage Trails dots. A memo of December 2, 1999 stated: “HTNY Dots on the ground need to be removed. Art Commission to be informed by HTNY. Nadine will provide cost estimate and recommend vendors for removal.”

Implementation was slow, but by autumn 2000, HTNY had started to remove the colored trail dots.

Indeed, it is hard to imagine that the Scotchprint dots would have lasted long on New York’s incessantly dug-up and patched-over pavements. The perennial and elusive goal of decades of planners to pedestrianize Downtown streets might have helped HTNY’s chances of maintaining a permanent path. But the idea of closing streets to cars and trucks met with strong resistance and was realized on Wall Street and elsewhere only after 9/11, and then entirely for security reasons.

It seems likely that the dots would have disappeared with time, long or short, but there can be no doubt that 9/11 speeded the process. New maps were needed for the site markers, and some panels needed to be removed or rewritten. The path of the Orange Trail through the World Trade Center to the World Financial Center (now Brookfield Place) was inaccessible for fifteen years, and even after the urban connection has been reopened, the site markers are lost. Indeed, today the only original history panel is the one that World Trade Center survives in the 9/11 Memorial and Museum.

In the end, Heritage Trails was an exemplary idea, creative in concept and designed by people with talent, energy, and resources. But, as Frank Sinatra sang, New York can be a tough town to “make it.” Smaller cities have managed to create both an enduring tourist attraction and a community identity based on a focused history. Boston and Philadelphia have forged identities as colonial and Revolutionary War-era cities celebrating Freedom and Independence at related historic sites. Chicago promotes its great architectural heritage and has an organization that mounts exhibitions, marshals hundreds of trained volunteer docents to lead tourists on ticketed tours, and that also reaches kids in public schools with educational resources. New York has never had a single, signature trail or a comparable civic organization.

That many of the markers have vanished, and none survive in their original state, speaks to the cycle of “urban oblivion” that Richard Kaplan had evoked to describe the lost 1976 Bicentennial panels. Now, another twenty years later, The Skyscraper Museum is pleased to have reconstructed and revived Heritage Trails, not just in the history recorded here, but in a “digital footprint” that visitors can experience anywhere online, as well as, again, on the streets of lower Manhattan.

Text by Carol Willis & Mary Beth Betts

CLICK ON THE MAP TO LAUNCH THE DIGITAL HERITAGE TRAILS, 1997/ 2017