The Skyscraper Museum is devoted to the study of high-rise building, past, present, and future. The Museum explores tall buildings as objects of design, products of technology, sites of construction, investments in real estate, and places of work and residence. This site will look better in a browser that supports web standards, but it is accessible to any browser or Internet device.

Skyline, 1930 - The Third Period

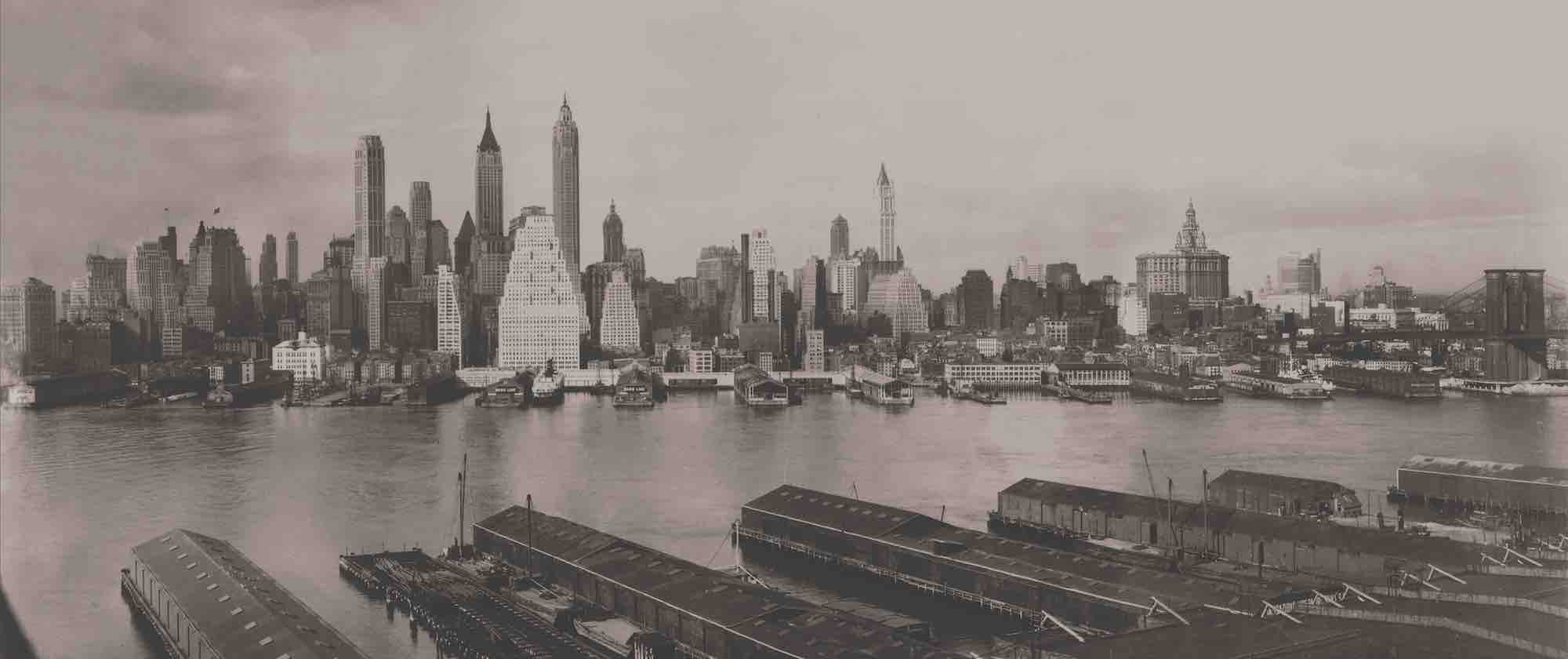

Top: Lower Manhattan from Jersey City, 1932. Irving Underhill. Courtesy of the Woolworth Building.

Below: Lower Manhattan from Brooklyn, ,1931. Iring Underhill, Library of Congress.

Two Irving Underhill perspectives of lower Manhattan in the early 1930s, seen from across the Hudson (top) and from Brooklyn, show the characteristic setbacks and slender towers that shaped the downtown skyline after 1916 and until the early 1960s. There was a new scale of the tallest towers, which rose to between 50 and 71 stories and crowded on and near Wall Street, representing the peaks of land values in that area.

It was government regulation -– New York’s first zoning law, passed in 1916 – that sculpted these skyscrapers into ziggurats and pyramidal bases with slender tower shafts. Rather than the blocky, straight-up sides of the high-rises of the previous decades, these buildings followed rules that, after a certain height above the sidewalk, required the mass to step back as it rose. This setback formula was designed to preserve a measure of light and air for the streets below and better access to light for the workers on upper floors. In addition, a tower of unlimited height was allowed over one quarter of the area of the lot – thus producing the spindly shafts of the Wall Street cluster. The details of the zoning formula are illustrated in a model case in the gallery.

Bottom: Royal Insurance Building, 150 William Street, and Bank of America Building at 44 Wall Street, Irving Underhill, 1927. Collection of The Skyscraper Museum.

Far right: 40 Wall Street illustration. Plate from Starrett Brothers and Eken, Inc., Builders, A portfolio of photographs of office buildings, hospitals, university buildings, industrial plants, financial houses, housing projects, apartment houses, department stores, insurance company home offices, 1925 – 1931. Gift of HRH Construction, Collection of The Skyscraper Museum.

The impact of the zoning law was delayed initially by a lag in construction during World War I and the long postwar recovery. Activity resumed around 1923, and one of the first major projects designed under the new regulations was the New York Telephone Building, which filled the block between Barclay and Vesey streets and fronted on West Street (at far left of the top photo). This mountain-like pile combined offices in the tower section and acres of mechanical operations in the deep base, so its unusually massive size and distance from the Financial District were logical. The design by architect Ralph Walker was heralded by critics as one of the first “modern” skyscrapers of the new era.

In the East River view, a trio of white buildings illustrates the ziggurat form prescribed by the zoning law and adapted to different size lots. The largest is the 33-story 120 Wall Street, completed in 1930 and notable for its “wedding cake” shape and wide façade on South Street. Its slightly asymmetric profile and abundant dormer sections followed the zoning template precisely and squeezed every cubic foot of rentable space allowed by the code.

These views of 1931 and 1932 capture the downtown skyline after it peaked as a result of the surging stock market of the “Roaring Twenties” and after the crash in October 1929. Most high-rise projects continued after Black Tuesday and well into 1930, but as the recession deepened into the Great Depression by 1932, no new skyscrapers were started in lower Manhattan until the 1950s.

NEXT: IMPACT OF 1916 ZONING