The Skyscraper Museum is devoted to the study of high-rise building, past, present, and future. The Museum explores tall buildings as objects of design, products of technology, sites of construction, investments in real estate, and places of work and residence. This site will look better in a browser that supports web standards, but it is accessible to any browser or Internet device.

Skyline, 1900 - 1916

By the turn of the century, as the 1902 panorama by the commercial photographer Irving Underhill shows, the lower Manhattan skyline had filled in considerably and grown much taller. The majority of high-rise construction began after 1890, when the World Building topped out at 309 feet, and accelerated in the years after 1893 with a spate of new towers. The boom related to advances in building technologies, including steel-skeleton construction, caisson foundations, and more efficient elevators, and it continued even in the wake of the Panic of 1893, a worldwide financial crisis. The skyline changed most dramatically in the last three years of the century: an 1896 photograph by William W. Silver in an oval pictures an earlier silhouette with towers widely spaced, like charms on a beginner’s bracelet. By 1900, the Park Row Building with its twin cupolas stretching to 391 feet, anchored a cluster of skyscrapers around City Hall, and skyscrapers crowded lower Broadway.

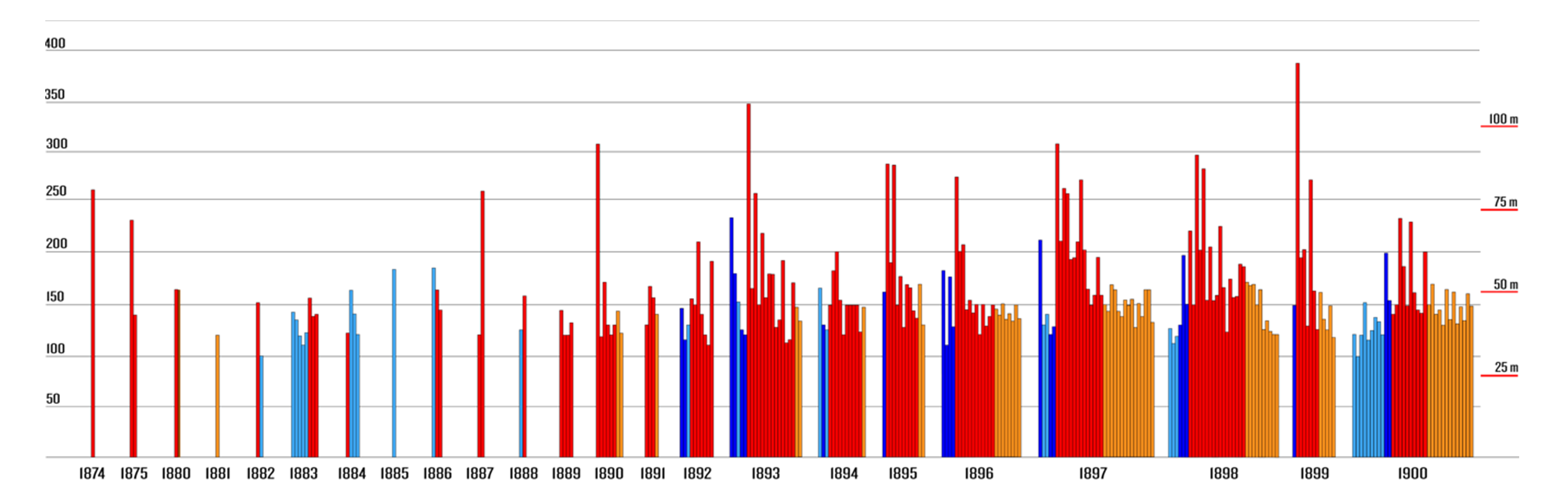

According to a survey of building permits, from 1874 to 1900, there were a total of 252 structures erected in Manhattan that were ten stories or taller. The Museum charted them all in a timeline seen above: each colored bar represents a building by date, height, and use: red for office buildings, blue for residential and hotels, and orange for lofts. While these structures spread across the island, the greatest concentration was office buildings in lower Manhattan. The ten tallest buildings in New York in 1900 were all located south of Chambers Street.

Park Row Building, 1899 – 391 ft.Manhattan Life Insurance, 1893 – 348 ft.

St. Paul Building, 1897 – 315 ft.

American Surety, 1895 – 312 ft.

World Building, 1890 – 309 ft.

Commercial Cable Building, 1897 – 304 ft.

American Tract Society, 1895 – 291 ft.

Empire Building, 1898 – 287 ft.

Standard Oil Building, expanded, 1899 – 280 ft.

Gillender Building, 1897 – 273 ft.

Most of these can be seen in the 1902 Underhill photograph. The mix of rooflines, flat-topped and jagged, illustrate the eclecticism of New York architecture in the last years of the nineteenth century when the skyline was the arena of stylistic battles between picturesque profiles and classical cornices. The attachment to historical precedents lasted through the 1910s, as is clear in the panorama on the right, dominated by the neo-Gothic 1913 Woolworth Building, the ‘Cathedral of Commerce.’

What forces drove this vertical climb in the mid-1890s? Broadly, the rapid expansion of both population and businesses. In 1880, the city’s population was about 1.2 million: by 1900, it was more than 3.4 million. This growth fueled a wave of work and investment in buildings across the city, and especially in lower Manhattan where local, national, and international companies competed for space for their workers and headquarters. In an early article on the dynamic of rising land prices, The Lofty Buildings of New York City,” in October 1896, Scientific American noted “an appreciation in the value of land for which no parallel can be found in any city of the world.” Citing the concentration of vast commercial interests within a restricted area and the prevalence of steel-frame construction, which had “quadrupled the size of building…formerly possible to erect upon a given area,” the anonymous author observed: “in regard to the relation of land values to the height of buildings, the effect has, in some measure, become the cause.”

NEXT: SKYLINE THROUGH 1916