The Skyscraper Museum is devoted to the study of high-rise building, past, present, and future. The Museum explores tall buildings as objects of design, products of technology, sites of construction, investments in real estate, and places of work and residence. This site will look better in a browser that supports web standards, but it is accessible to any browser or Internet device.

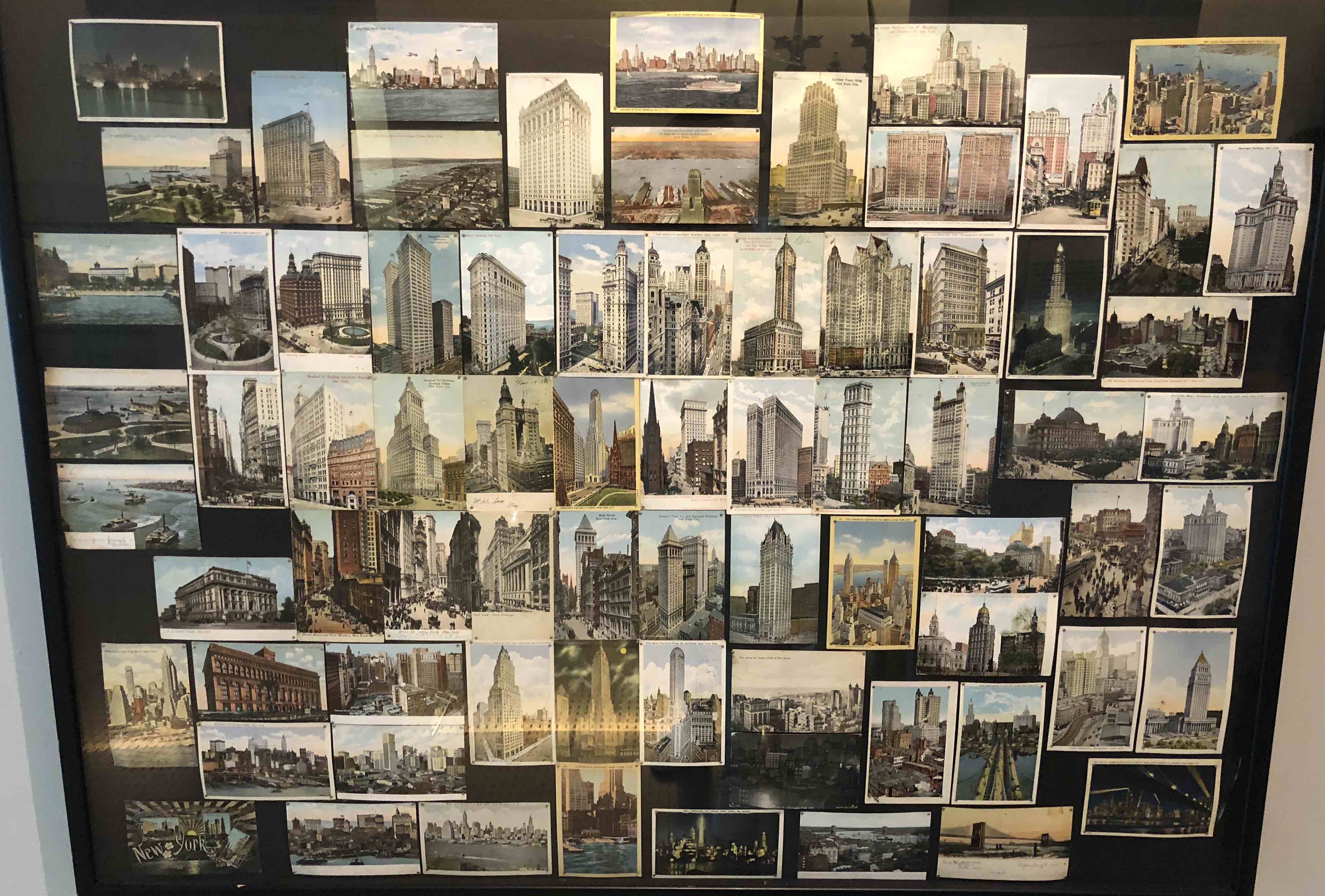

SKYSCRAPER POSTCARDS

Click here to view the SKYLINE postcards

Click here to view the SKYLINE postcards

The cultural phenomenon of picture postcards is captured in an example from 1901 in the frame above the screen, where more images of the New York skyline can be viewed. A father writes to his son: “You want to get a scrap book and save souvenir postals. They make a dandy collection and you can get them from all parts of the world. When anyone goes away get them to send you a postal.” Postcards were inexpensive souvenirs – simple records to remember a place visited, or a way to share an experience with friends or relatives. As other cards reveal in their messages, they were also a means to send a quick note of news, cheaper than a telegram, but almost as timely, given the efficient postal service of those days.

Postcard collecting was popular in Europe before it was introduced to America at the 1893 World Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Before May 19, 1898, only the U.S. Post Office could print postcards, but after Congress passed the Private Mailing Card Act, private publishers and printers expanded the market. By 1904, the Post Office was delivering 700 million postcards in a single year: at the peak of the craze in 1913, the number was 968 million, when the entire population of the U.S. was only 97 million.

Skyscrapers and city views were popular subjects for cards. They evoked a strong sense of place and scenes that were unique to New York. Skyline views were often produced in multi-fold cards to encompass a panorama, especially from the rivers. Many postcards featured single buildings, almost portrait-like, and these images preserve both a particular moment in time and provide an important historical record. In addition to the popular colored picture postcards, many of which around the turn of the century were lithographs printed in Germany, real-photo postcards reproduced from negatives directly to special photographic paper appeared first in 1899. With the invention of high-speed photo printers in 1910, real-photo postcards became more common and affordable. Many of the greatest images of the skyline were taken by commercial photographers for postcard views.

The postcards date from c.1900 through the 1930s and were collected by Carol Willis. Arranged based on their geographic location in Lower Manhattan, postcards depicting The Hudson River are along the top, New York Harbor is on the left, and the East River is along the bottom.

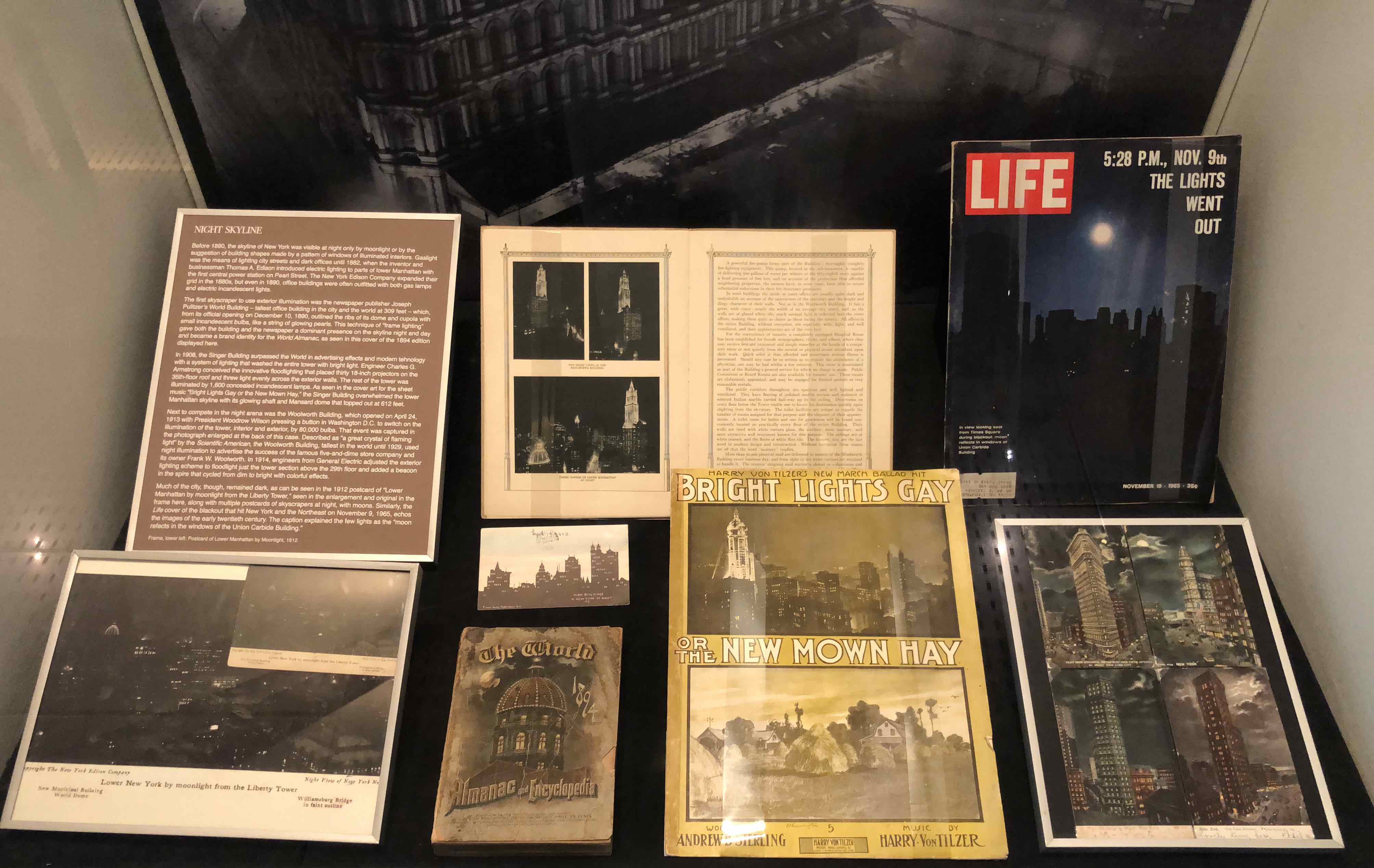

NIGHT SKYLINE

Before 1890, the skyline of New York was visible at night only by moonlight or by the suggestion of building shapes made by a pattern of windows of illuminated interiors. Gaslight was the means of lighting city streets and dark offices until 1882, when the inventor and businessman Thomas A. Edison introduced electric lighting to parts of lower Manhattan with the first central power station on Pearl Street. The New York Edison Company expanded their grid in the 1880s, but even in 1890, office buildings were often outfitted with both gas lamps and electric incandescent lights.

The first skyscraper to use exterior illumination was the newspaper publisher Joseph Pulitzer’s World Building – tallest office building in the city and the world at 309 feet – which, from its official opening on December 10, 1890, outlined the ribs of its dome and cupola with small incandescent bulbs, like a string of glowing pearls. This technique of “frame lighting” gave both the building and the newspaper a dominant presence on the skyline night and day and became a brand identity for the World Almanac, as seen in this cover of the 1894 edition displayed here.

Woolworth Building, 1913. Library of Congress

In 1908, the Singer Building surpassed the World in advertising effects and modern tehnology with a system of lighting that washed the entire tower with bright light. EngineerCharles G. Armstrong conceived the innovative floodlighting that placed thirty 18-inch projectors on the 35th-floor roof and threw light evenly across the exterior walls. The rest of the tower was illuminated by 1,600 concealed incandescent lamps. As seen in the cover art for the sheet music “Bright Lights Gay or the New Mown Hay,” the Singer Building overwhelmed the lower Manhattan skyline with its glowing shaft and Mansard dome that topped out at 612 feet.

Next to compete in the night arena was the Woolworth Building, which opened on April 24, 1913 with President Woodrow Wilson pressing a button in Washington D.C. to switch on the illumination of the tower, interior and exterior, by 80,000 bulbs. That event was captured in the photograph enlarged at the back of this case. Described as “a great crystal of flaming light” by the Scientific American, the Woolworth Building, tallest in the world until 1929, used night illumination to advertise the success of the famous five-and-dime store company and its owner Frank W. Woolworth. In 1914, engineers from General Electric adjusted the exterior lighting scheme to floodlight just the tower section above the 29th floor and added a beacon in the spire that cycled from dim to bright with colorful effects.

Much of the city, though, remained dark, as can be seen in the 1912 postcard of “Lower Manhattan by moonlight from the Liberty Tower,” seen in the enlargement and original in the frame here, along with multiple postcards of skyscrapers at night, with moons. Similarly, the Life cover of the blackout that hit New York and the Northeast on November 9, 1965, echos the images of the early twentieth century. The caption explained the few lights as the “moon refects in the windows of the Union Carbide Building.

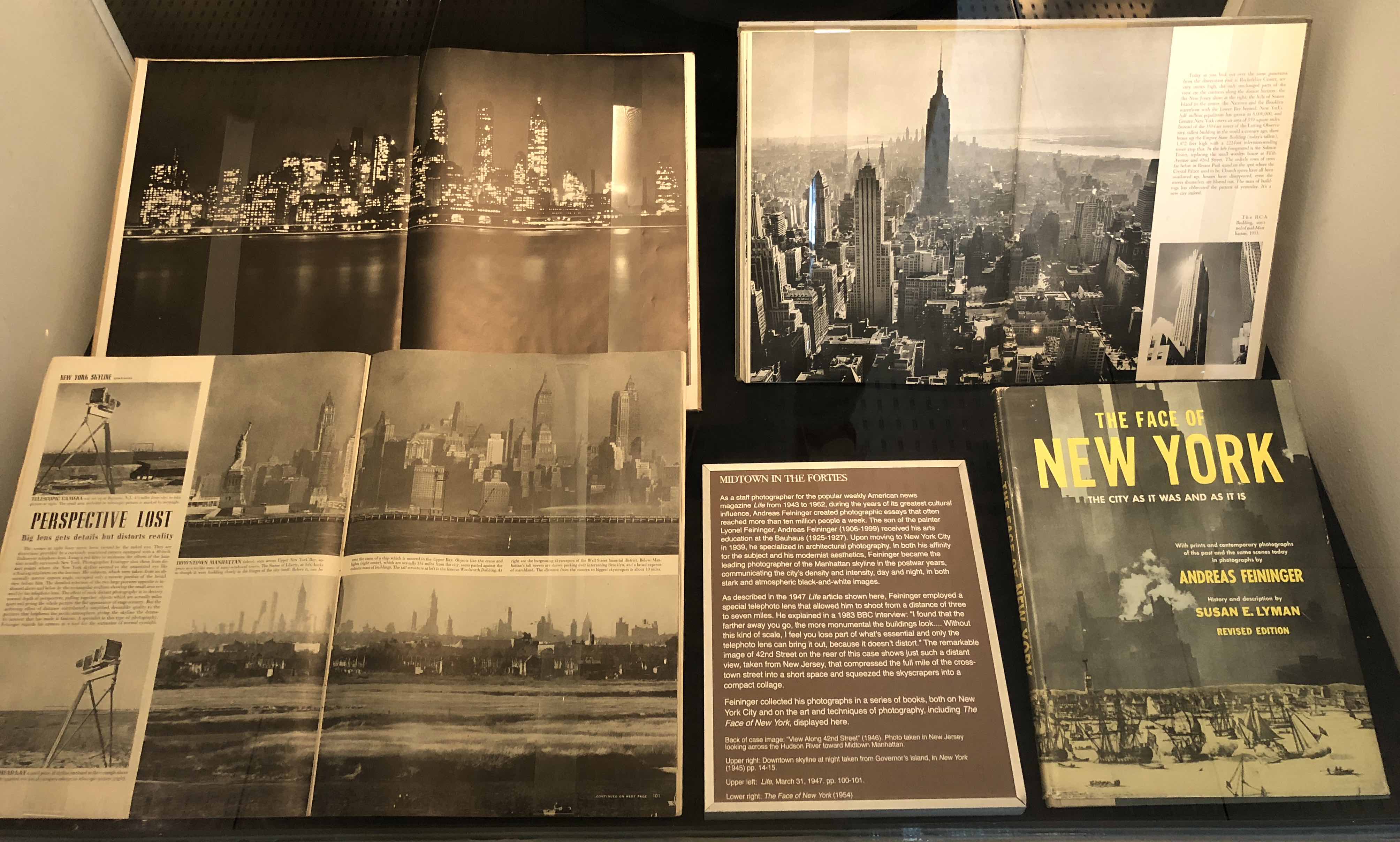

MIDTOWN IN THE FORTIES

Back of case image: “View Along 42nd Street” (1946). Photo taken in New Jersey looking across the Hudson River toward Midtown Manhattan. Upper right: Downtown skyline at night taken from Governor’s Island, in New York (1945) pp. 14-15. Upper left: Life, March 31, 1947. pp. 100-101. Lower right: The Face of New York (1954)

Back of case image: “View Along 42nd Street” (1946). Photo taken in New Jersey looking across the Hudson River toward Midtown Manhattan. Upper right: Downtown skyline at night taken from Governor’s Island, in New York (1945) pp. 14-15. Upper left: Life, March 31, 1947. pp. 100-101. Lower right: The Face of New York (1954)

As a staff photographer for the popular weekly American news magazine Life from 1943 to 1962, during the years of its greatest cultural influence, Andreas Feininger created photographic essays that often reached more than ten million people a week. The son of the painter Lyonel Feininger, Andreas Feininger (1906-1999) received his arts education at the Bauhaus (1925-1927). Upon moving to New York City in 1939, he specialized in architectural photography. In both his affinity for the subject and his modernist aesthetics, Feininger became the leading photographer of the Manhattan skyline in the postwar years, communicating the city’s density and intensity, day and night, in both stark and atmospheric black-and-white images.

As described in the 1947 Life article shown here, Feininger employed a special telephoto lens that allowed him to shoot from a distance of three to seven miles. He explained in a 1983 BBC interview: “I found that the farther away you go, the more monumental the buildings look.... Without this kind of scale, I feel you lose part of what’s essential and only the telephoto lens can bring it out, because it doesn’t distort.” The remarkable image of 42nd Street on the rear of this case shows just such a distant view, taken from New Jersey, that compressed the full mile of the cross-town street into a short space and squeezed the skyscrapers into a compact collage. Feininger collected his photographs in a series of books, both on New York City and on the art and techniques of photography, including The Face of New York, displayed here.NEXT: SKYLINE 2018+