The Skyscraper Museum is devoted to the study of high-rise building, past, present, and future. The Museum explores tall buildings as objects of design, products of technology, sites of construction, investments in real estate, and places of work and residence. This site will look better in a browser that supports web standards, but it is accessible to any browser or Internet device.

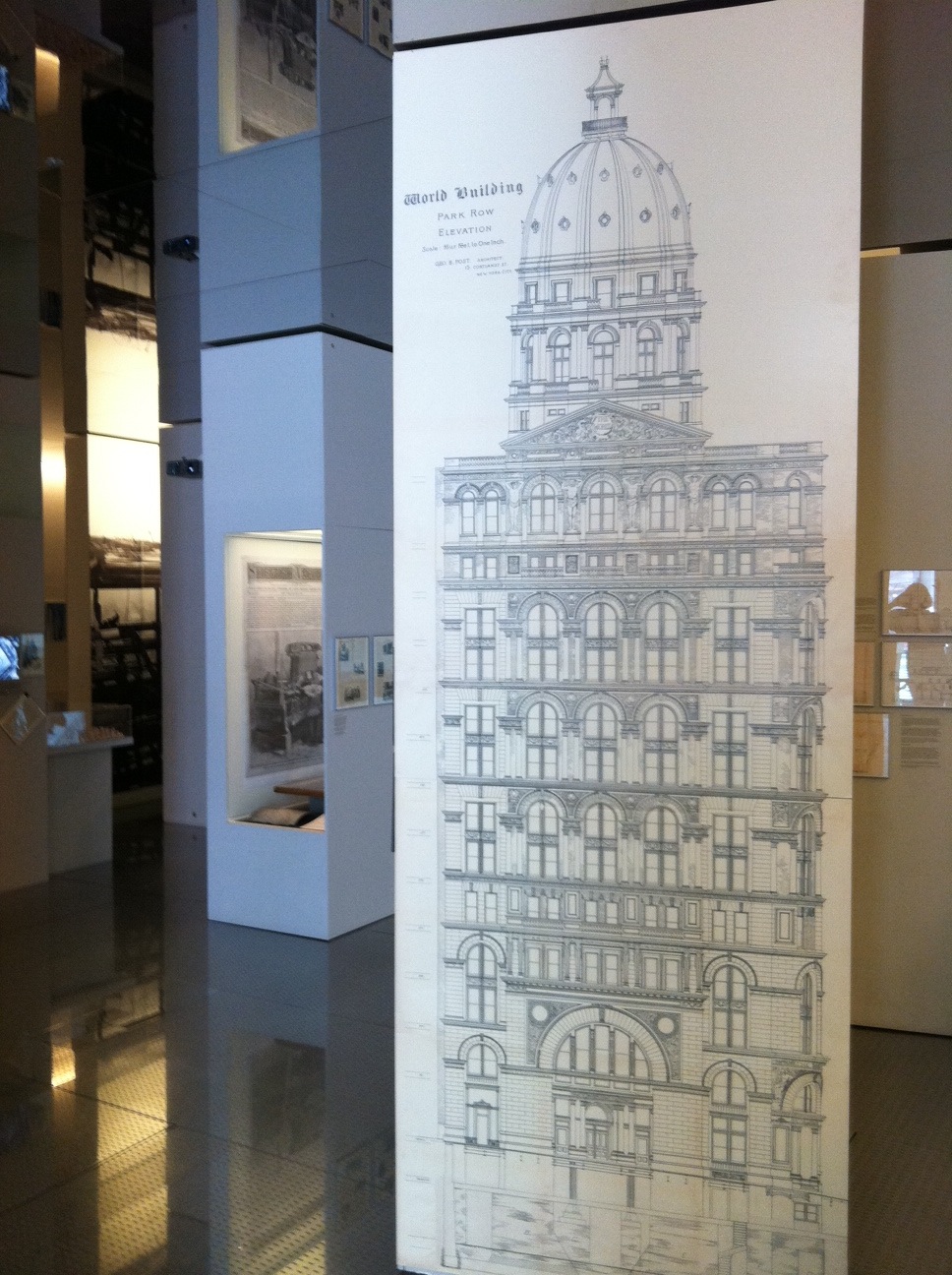

PULITZER'S WORLD BUILDING

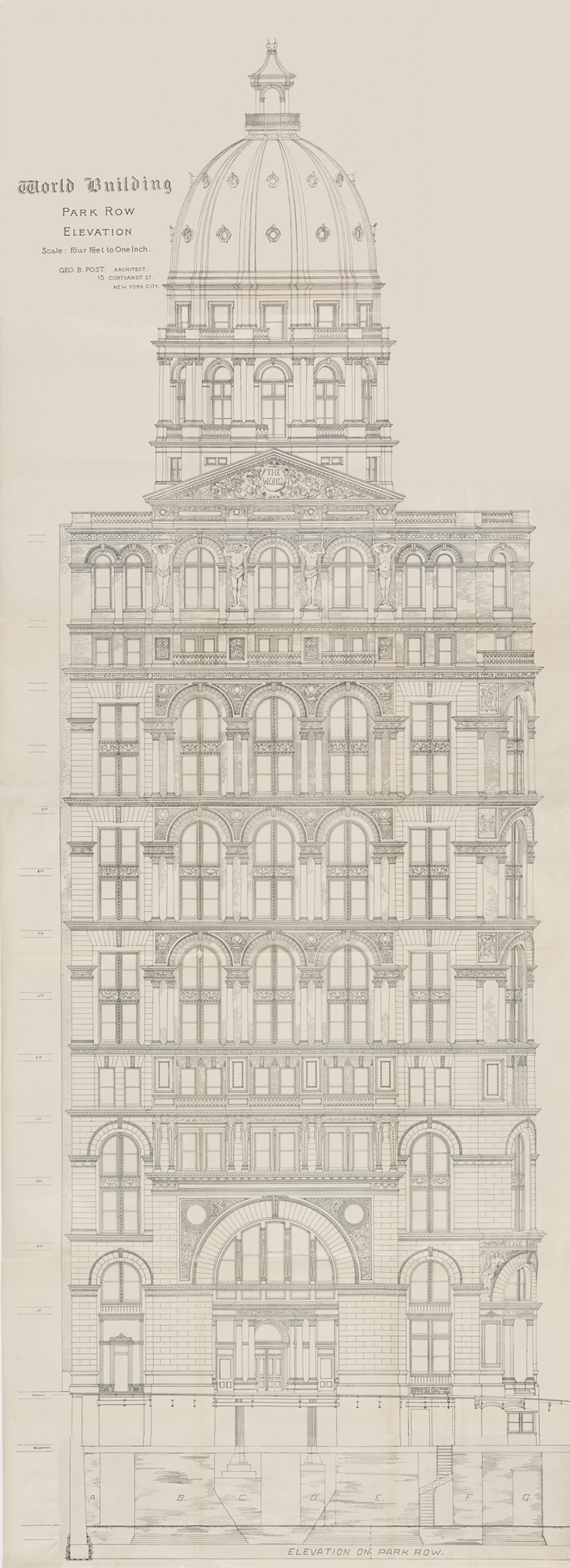

Completed in December 1890, the World Building, officially called the Pulitzer Building, was an expression of the ambitions and business genius of its publisher Joseph Pulitzer. At a height of 309 feet to the top of the dome, the World's new home became the highest building in the city and the tallest office building in the world.

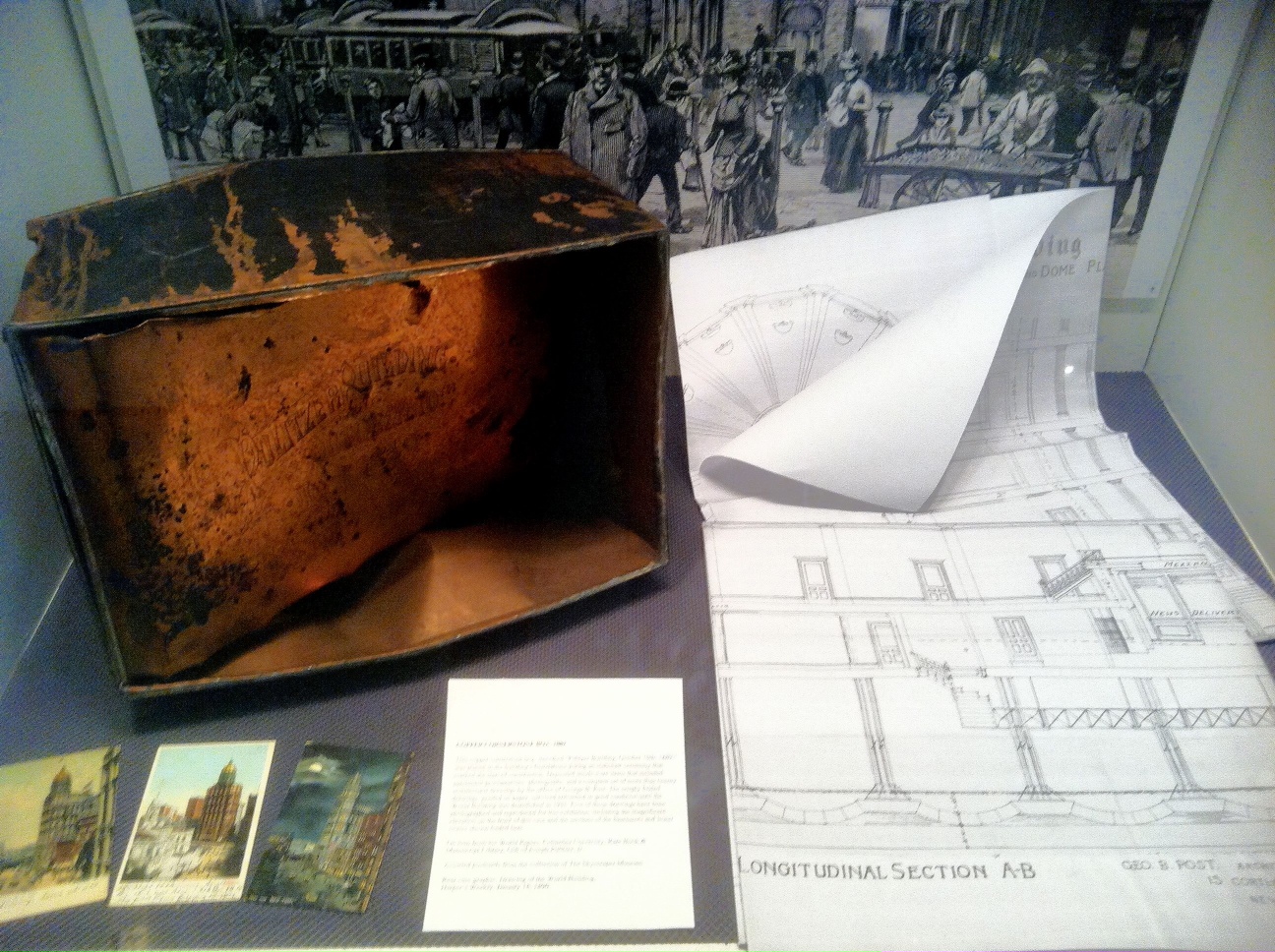

This copper cornerstone box, inscribed "Pulitzer Building, October 10th, 1889," was placed in the building's foundations during an elaborate ceremony that marked the start of construction. Deposited inside were items that included parchment proclamations, photographs, and a complete set of more than twenty architectural drawings by the office of George B. Post. The crisply folded drawings, printed on paper, survived entombed in good condition until the World Building was demolished in 1955. Five of those drawings have been photographed and reproduced for this exhibition, including the magnificent elevation on the front of this case and the sections of the basements and lower stories shown folded here.

On loan from the World Papers, Columbia University, Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Gift of Joseph Pulitzer, Jr.

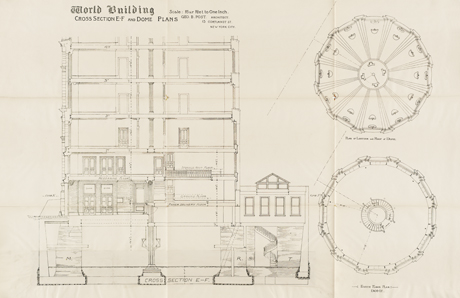

CROSS SECTION E-F

Pictured above is a cross-sectional drawing of the World Building that illustrates the iron structure and thickness of the exterior walls. These walls were not designed for stress but were the prescribed thicknesses in the New York City building code (Sections 476-477 in 1887). The progression of wall thickness down the building (including sub-grade levels) is masked at the street facade by the presence of ornamental masonry.

On the right is a 4th floor plan drawing of the dome that illustrates the ring of steel I-beams that curve to form the dome's structure.

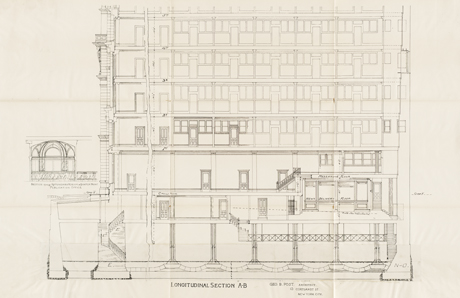

LONGITUDINAL SECTION A-B

Pictured above is the rear fa�ade (the wall above the foundation pier labeled N-O) illustrating the wall thicknesses required by the New York City building code. The walls have "strip footings" consisting of large stones (probably granite) with brick above. The interior cast-iron columns have inverted-arch masonry foundations, which were popular in the 2nd half of the 19th century but were not the most stable since masonry arches deform and can fail under unbalanced loading. This type of foundation was abandoned in large buildings before 1900.

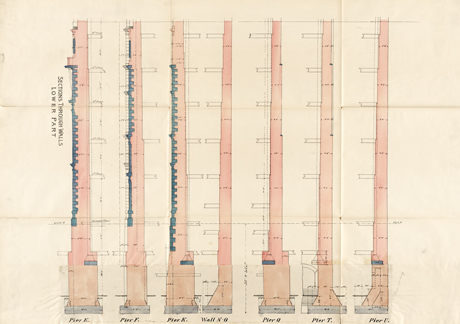

WALL SECTIONS AND CELLAR PLAN

The wall section drawings pictured depict the wall thicknesses required by NYC building code. The World Building was a "cage frame" building, which means that the iron structure carried all of the floor loads and had self-supporting exterior walls. The spandrel columns were buried within the wall at the basement floor but became visible on higher floors as the walls became thinner.

The blue rectangles at piers E, K, Q, and U located at the basement floor level are the granite foundation blocks for the columns. The truncated triangles above the column foundations are the cast-iron base plates (the sloped portions are vertically-oriented stiffener plates), and the columns are dashed above. At Pier U, the column would be completely invisible - buried in brick - at the first floor, whereas at the others, it is partly exposed.

In order for the cage frame to be stable, the interior floors had to be connected to the exterior walls, which provided all of the lateral-load strength. Note that at the 5th floor of Piers K and T the floor beams extend past the spandrel columns to tie to the walls.

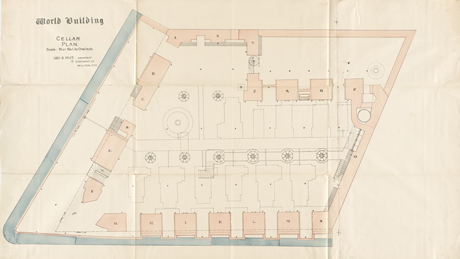

The image below illustrates different wall thicknesses. The exterior wall piers are so big in part because they are isolated piers rather than a continuous wall. By code, the plan section area of wall had to remain constant, so if a wall was broken up into piers, the piers had to be thicker than the original wall. Their difference in thickness can be seen when comparing the street-side piers to the rear-lot continuous walls. The spoked wheels are the cast-iron column base plates with stiffeners. The lines connecting those are the inverted arches. The sidewalk vault is the only column-free space.

Drawings by George B. Post, reproduced from the World Papers, Columbia University, Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Gift of Joseph Pulitzer, Jr.

Illustration captions prepared by Donald Friedman, PE, a structural engineer who leads Old Structures Engineering, PC.