The Skyscraper Museum is devoted to the study of high-rise building, past, present, and future. The Museum explores tall buildings as objects of design, products of technology, sites of construction, investments in real estate, and places of work and residence. This site will look better in a browser that supports web standards, but it is accessible to any browser or Internet device.

1900

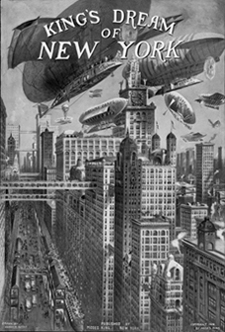

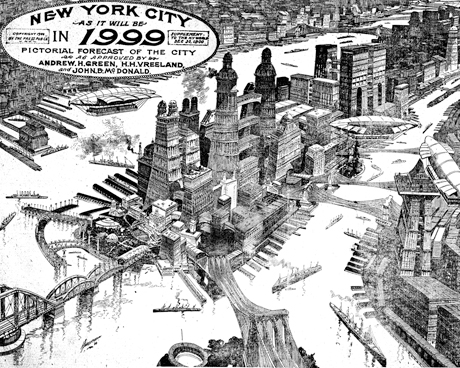

Images in magazines and the lavish editions of the popular souvenir books King's Views of New York typify prophecies of the urban future in the early twentieth century. Commercial artists and cartoonists imagined a metropolis of giant crowding towers-chaotic, congested, and teeming with new technologies of elevated trains and flying machines.

Left: "King's Dream of New York," from King's Views of New York, 1908-1909. Delineator: Harry Pettit; Published by Moses King, 1908. Right: King's Views of New York. 1911-1912, Cover Plate. Delineator: Richard Rummell; Published by Moses King, 1911.

At a time when no zoning laws limited heights or lot coverage, these predictions simply enlarged the trends and problems of the contemporary city. Traffic congestion was an obsession. The drawing from the 1908 King's Views envisioned a vista up Broadway as a canyon of motley office blocks with bridges springing from one rooftop to the next or tunneling through upper floors. The top of the Singer Tower, then the world's tallest skyscraper at 612 feet, is visible at the far left, but overtopped by the giants of the future.

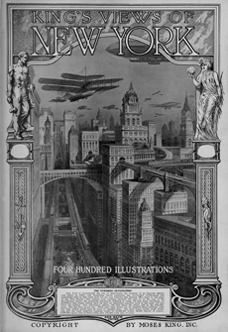

"New York City as it Will be in 1999," The New York World, December 30, 1900, supplement foldout. Illustrator: Louis Biedermann

Joseph Pulitzer's New York World was one of the most widely read newspapers of its day. The Sunday edition, which could sell as many as half a million or more copies around the United States, was filled with colorful artwork, cartoons, and cultural commentary. At the turn of the twentieth century, one of the World's most popular illustrators, Louis Biedermann, speculated on the future New York in 1999 in a lavish two-page spread that pictured Manhattan solidly packed with skyscrapers, including behemoth towers at least a hundred-stories tall, sporting landing platforms of airships.

At a time when there were no controls on high-rise development, Biedermann's illustration exaggerated present trends and technologies and reflected both the fascination and fears of unconstrained growth.

Both Life and Cosmopolitan Magazine began publishing in the 1880s. Life, a weekly magazine focused on issues of general interest and humor and regularly featured illustrations, jokes and social commentary. Cosmopolitan began as a family publication and was taken over by William Randolph Hearst in 1905.

Left: "Wireless," Life Magazine, August 17, 1911, 263. Center: "New York To Boston in Forty Minutes," Life Magazine, May 29, 1913, 1083. Right: "Man's Machine-Made Millennium," Hudson Maxim, Cosmopolitan Magazine, November 1908, 569-577.

These three images from Life, illustrated by R.G. Russom, appeared in separate issues published during the early 1910s, each present futuristic visions for mass transportation�a vision that saw cars, trains and flying machines sharing the sky. With elevators bringing people up from street level to the elevated rail lines, roadways and walkways, these new and reinvented forms of transport were to alleviate the overcrowded city streets. These images juxtaposed people catching the express car to Boston and boarding the 20 Hour Flier to California with an arena for recreation, advertisement and public gatherings.

In his article for Cosmopolitan, Hudson Maxim declared that in the coming millennium, �the great city of the future will be as one enormous edifice.� In the accompanying illustration of New York City, William R. Leigh also included flying machines, elevated walkways and roadways.

High-above the city below, Life and Cosmopolitan offered to its readers, and more notably to American popular culture, a vision for the future with a completely transformed public realm.