The Skyscraper Museum is devoted to the study of high-rise building, past, present, and future. The Museum explores tall buildings as objects of design, products of technology, sites of construction, investments in real estate, and places of work and residence. This site will look better in a browser that supports web standards, but it is accessible to any browser or Internet device.

THE HISTORIC CORE

Michael Kwartler and the New School’s Environmental Simulation Center

Michael Kwartler and the New School’s Environmental Simulation Center

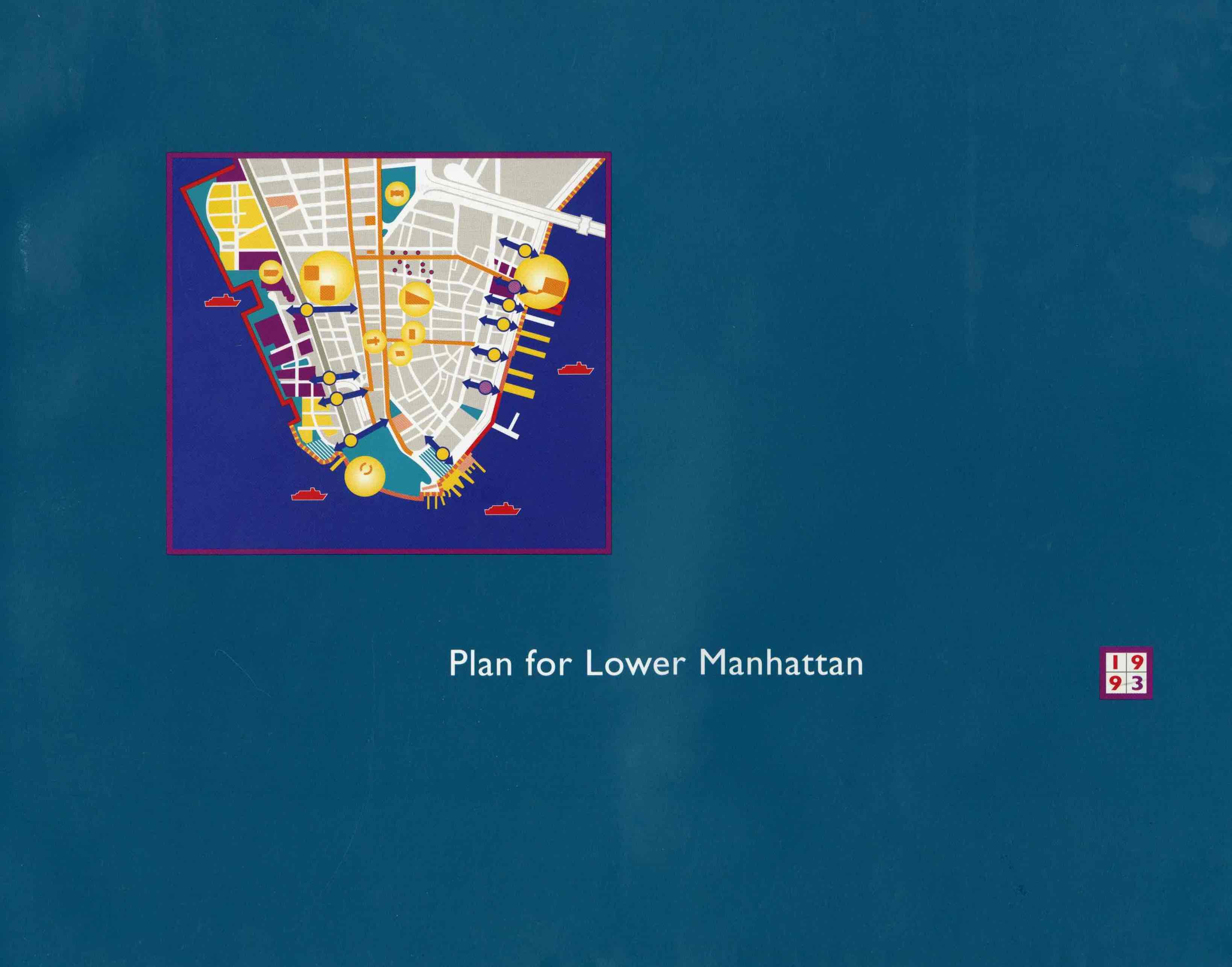

Plan for Lower Manhattan, 1993.

The City tried to address these problems with public policy initiatives. In 1993, the Dinkins Administration and the Department of City Planning issued its Plan for Lower Manhattan, shown below with its blue cover and an interior page, which analyzed the assets and challenges of Downtown and called for its reinvention as a more diversified “24/7” neighborhood.

Promoting the conversion of office buildings to residential use was a key concept, but developers were slow to respond. In 1994, the new Giuliani Administration and its Chairman of

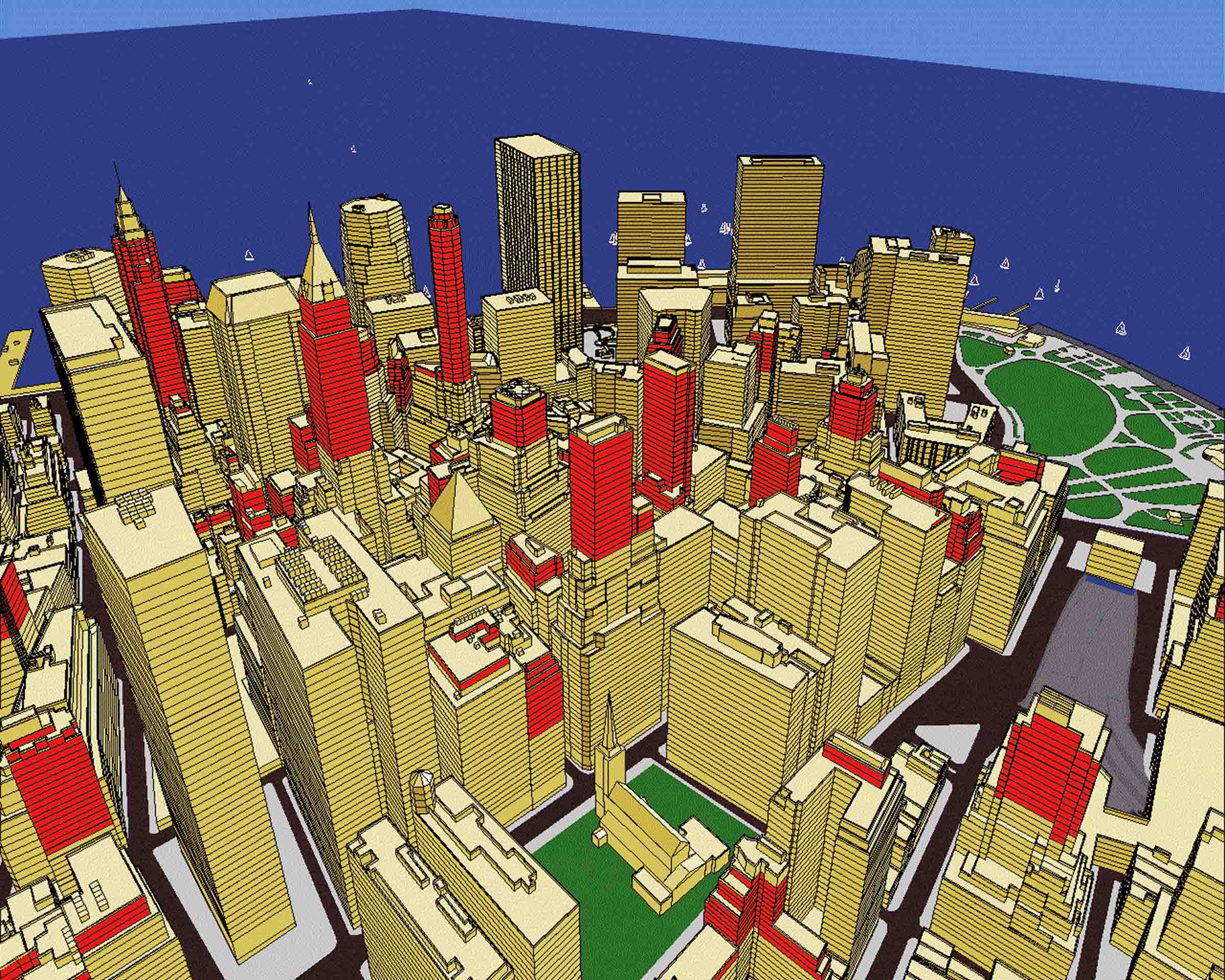

Installation view

The best candidates for residential conversion were not the older low-rise structures of 10 to 20 stories that lined the dense, dark “canyons” of the district, but the taller towers, mostly of the Twenties, that had good light, great views, and smaller floor plates that adapted to apartment floor plans. As illustrated in the image below, a study by Michael Kwartler and the New School’s Environmental Simulation Center, employed the then-new 3D geographic information system (GIS) to visualize statistics about Lower Manhattan and to create an digital model using data related to zoning, census, infrastructure, building construction and age, total floor area, and vacancy rates.

Michael Kwartler and the New School’s Environmental Simulation Center

The top image, which was published in the New York Times in a David Dunlap article, “Bringing Downtown Back Up,” (reproduced below) illustrated the amount of office space in pre-war buildings 150 ft. or more above the street – space that, at that time, was both primarily vacant and highly suitable for apartments. Another feature on the future of residential conversion in the Financial District, “Wall Street Wonderland,” appeared New York Magazine in November 1996.

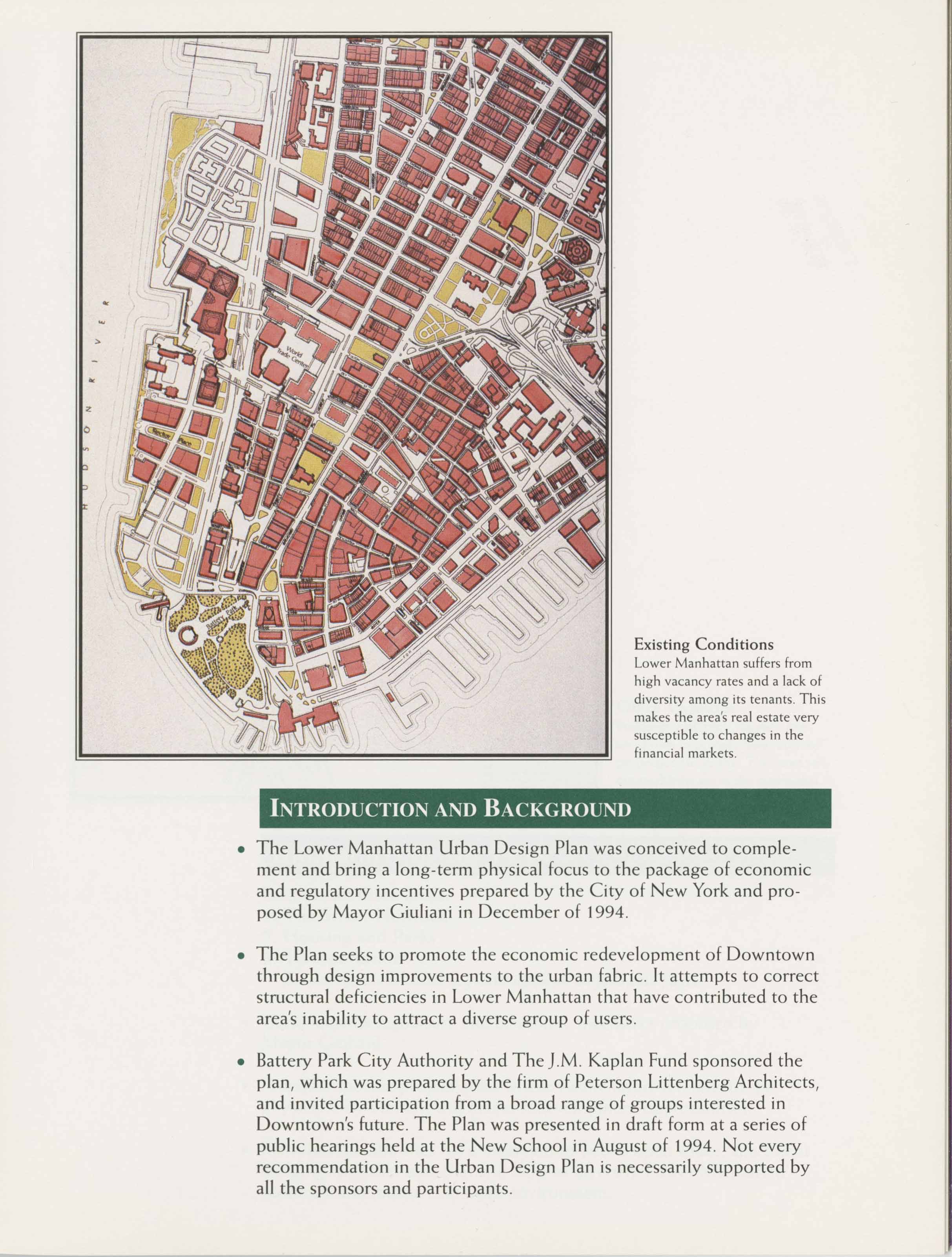

Lower Manhattan Urban Design Plan

Other city agencies, such as the New York City Economic Development Corporation (EDC) and State entities such as the Port Authority and the Battery Park City Authority, as well as professional and civic groups such as the Regional Plan Association and the Landmarks Conservancy, trained attention on transforming the district. One study funded and by the BPCA that received support from the J.M. Kaplan Fund was Peterson Littenberg Architects’ “Lower Manhattan Urban Design Plan” (middle frame) which “sought to promote the economic development of Downtown through design improvements to the urban fabric.” The plan was presented at a series of public hearings at the New School in August 1994.