The Skyscraper Museum is devoted to the study of high-rise building, past, present, and future. The Museum explores tall buildings as objects of design, products of technology, sites of construction, investments in real estate, and places of work and residence. This site will look better in a browser that supports web standards, but it is accessible to any browser or Internet device.

ROBERT F. WAGNER, JR. PARK

Model of early design for Wagner Park and Pavilion, 1993.

Machado Silvetti, collection of Battery Park City Authority.

Model of early design for Wagner Park and Pavilion, 1993.

Machado Silvetti, collection of Battery Park City Authority.

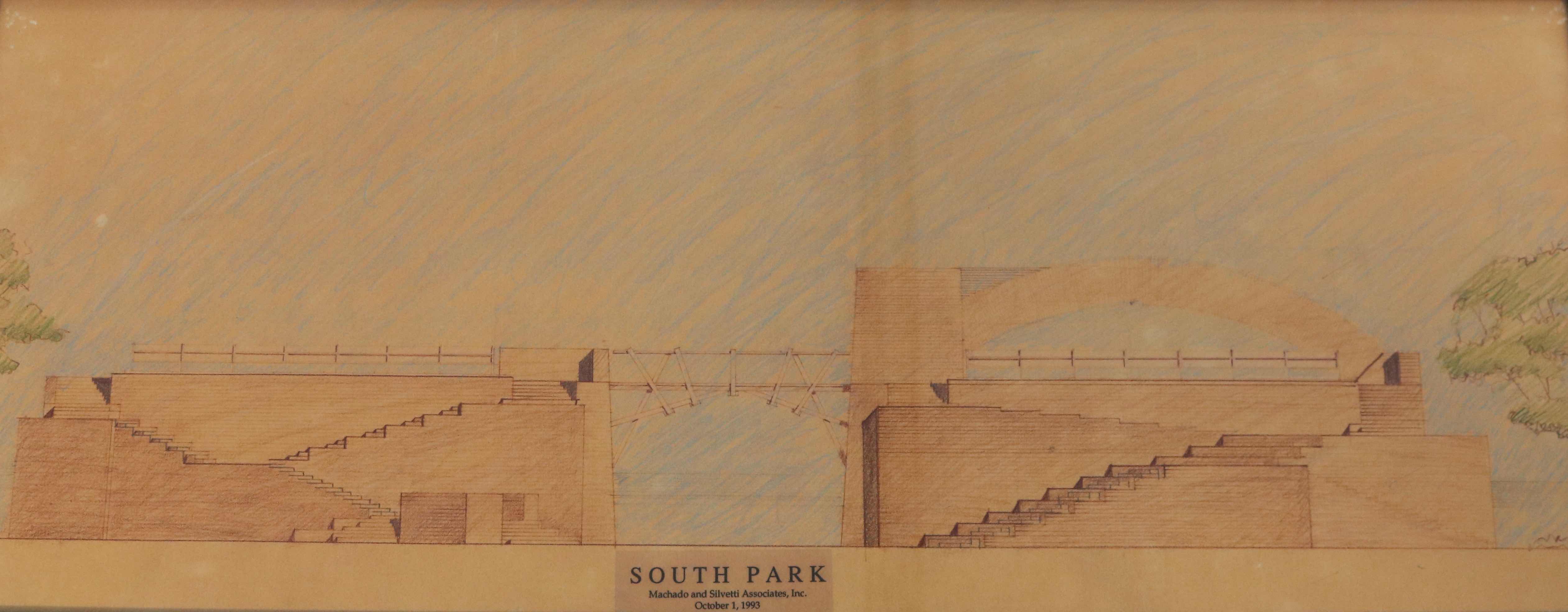

The model and framed drawing and in the case to the right are early schemes for the Robert F. Wagner Jr. Park and Pavilion, designed by the Boston-based firm Machado Silvetti. The park, directly across the street from The Skyscraper Museum, opened in 1996. The ensemble of architecture and landscape design, by Hanna/ Olin and garden designer Lynden B. Miller, features a grassy plane sloping down to the harbor and framed by two brick of pavilions joined by a wooden bridge. Rodolfo Machado describes the design in the statement below.

Watercolor drawing of Wagner Park Pavilion, October 1, 1993.

Machado Silvetti, collection of Battery Park City Authority.

Watercolor drawing of Wagner Park Pavilion, October 1, 1993.

Machado Silvetti, collection of Battery Park City Authority.

Robert F. Wagner, Jr. Park: An Urban Waterfront Park

Battery Park City, New York

Wagner Park Pavilion at Sunset, c. 1996 ©Machado Silvetti

The Robert F. Wagner, Jr. Park occupies a unique site characterized by its spectacular views of the Statue of Liberty and its relatively small area located at the center of colossal surroundings. The main function of this public place - the reason for its existence - is to provide a privileged viewing of the Statue of Liberty and the New York Harbor from a unique "point" along the New York waterfront.

The design of the park rests on three main components: a pair of allées that bring pedestrians from existing city sidewalks toward the main park entrance; a pair of pavilions connected by a bridge, constituting the main building; and a grass lawn framed by a continuous path and benches. This "Y" shaped architectural ensemble is the backbone of the park, resting in gardens that connect it to the Battery Park City Esplanade to the North and to Battery Park to the South.

The building is conceived as a large, over-scaled, massive masonry wall split in the center, framing (on approach) the view to the Statue. On the wall’s surfaces, a variety of brick patterns are displayed following a precise figurative symbolic strategy: the representation of a watchful, colossal, half-emerging face. This massive formation crumbles toward the city side to form a pair of large public steps that seemingly prolong the allées and bring the public up to a pair of balconies overlooking the lawn and harbor. From the center of the bridge connecting the two balconies, the viewer’s position relative to the Statue of Liberty is "face to face," direct.

This perspective drawing of the Plaza records an important moment along the design process, when we were freely playing with the Statue's attributes as material for the design of the space. Thus, the book-like paved ground represents the book in Liberty's hand, its pages becoming steps, etc.

The pavilions had, at some point, a pergola like canopy, such as the ones used in the excavation of ruins to protect them from the sun. We had a profound and rewarding dialogue with David Emil, then CEO of BPCA, and with Laurie Olin, our Landscape Architect, friend and Harvard colleague at that time. Often the late Mickey Friedman, Art Advisor, and Herbert Muschamp, the New York Times Architecture Critic, were part of the conversation as well. It was a splendid design process, of the kind rarely experienced today in designing significant public places.

Rodolpho Machado