The Skyscraper Museum is devoted to the study of high-rise building, past, present, and future. The Museum explores tall buildings as objects of design, products of technology, sites of construction, investments in real estate, and places of work and residence. This site will look better in a browser that supports web standards, but it is accessible to any browser or Internet device.

HERITAGE TRAILS NEW YORK

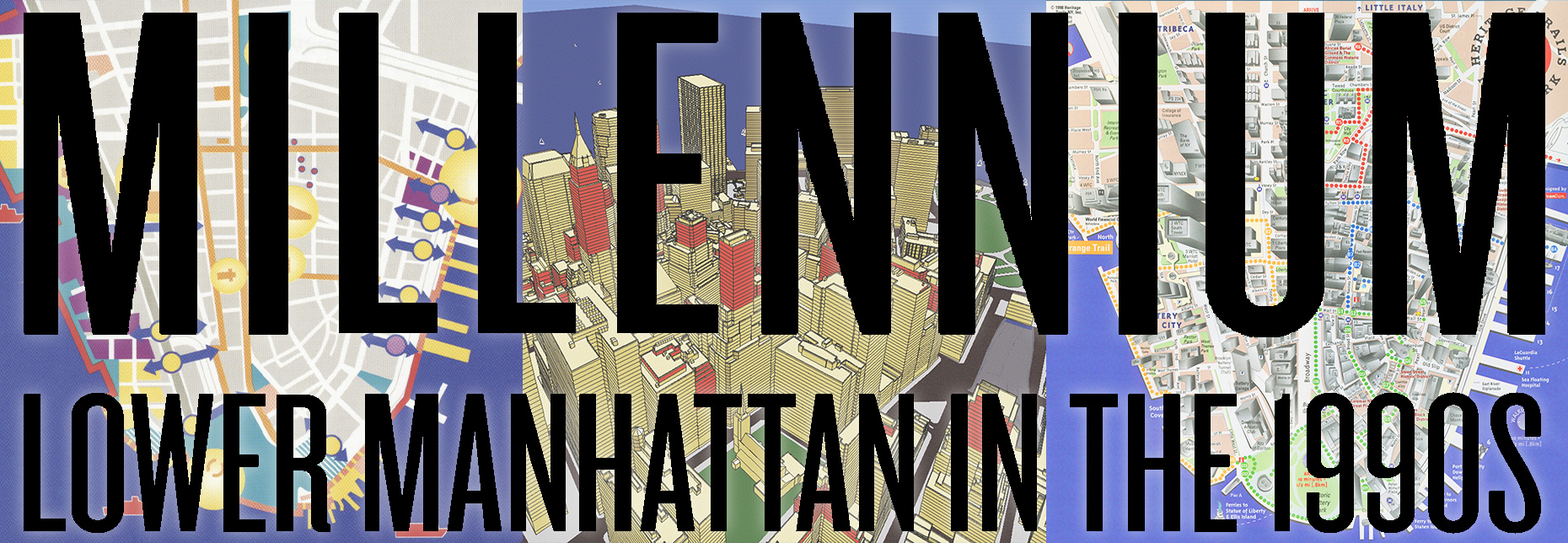

Heritage Trails New York (HTNY) was a landmark public history project of the mid-1990s focused on lower Manhattan – principally the square mile at the tip of the island, south of City Hall Park – the area that encompasses the historic core of the colonial city and the power center of the Financial District.

In 1998, when the project was largely complete, Heritage Trails comprised 40 site markers – stanchions and panels with images, interpretive texts, and a innovative 3D Downtown map. These were keyed to four trails, denoted by the colors Green, Blue, Red, and Orange, which tourists could follow with a free map pamphlet that

could be acquired at multiple information centers. Today, only 22 of

the original cast-iron stanchions survive on the streets and on those, both the text panels and map have been redesigned.

Heritage Trails New York was surprisingly short-lived. Without the cataclysmic disruption of September 11, 2001, perhaps HTNY would have become as much a fixture of Downtown’s identity as the Freedom Trail in Boston. But timing mattered: conceived in 1994 and completed five years later, Heritage Trails did not survive as a “brand” after 9/11.

The Skyscraper Museum undertook to retrieve the lost history of Heritage Trails and to commemorate the role of its driving force, Richard D. Kaplan, who died in 2016. Our project, which was to create a digital version of HTNY, had two main parts: to reconstruct the original marker panels from digital design files and to add a new panel that for each site addressed the twenty years from 1997 to 2017. The digital HTNY, which is keyed to a map and is interactive, can be viewed in the gallery on a touchscreen, as well as on our website. In the installation, a selection of the 1997 markers and 2017 updates were paired in frames, so visitors could read the "then-and-now" versions together. For this online presentation, the order has been reversed, with the 2017 panel placed first and the original marker's text placed second and distinguished as gray text.

World Trade Center

World Trade Center (2017)

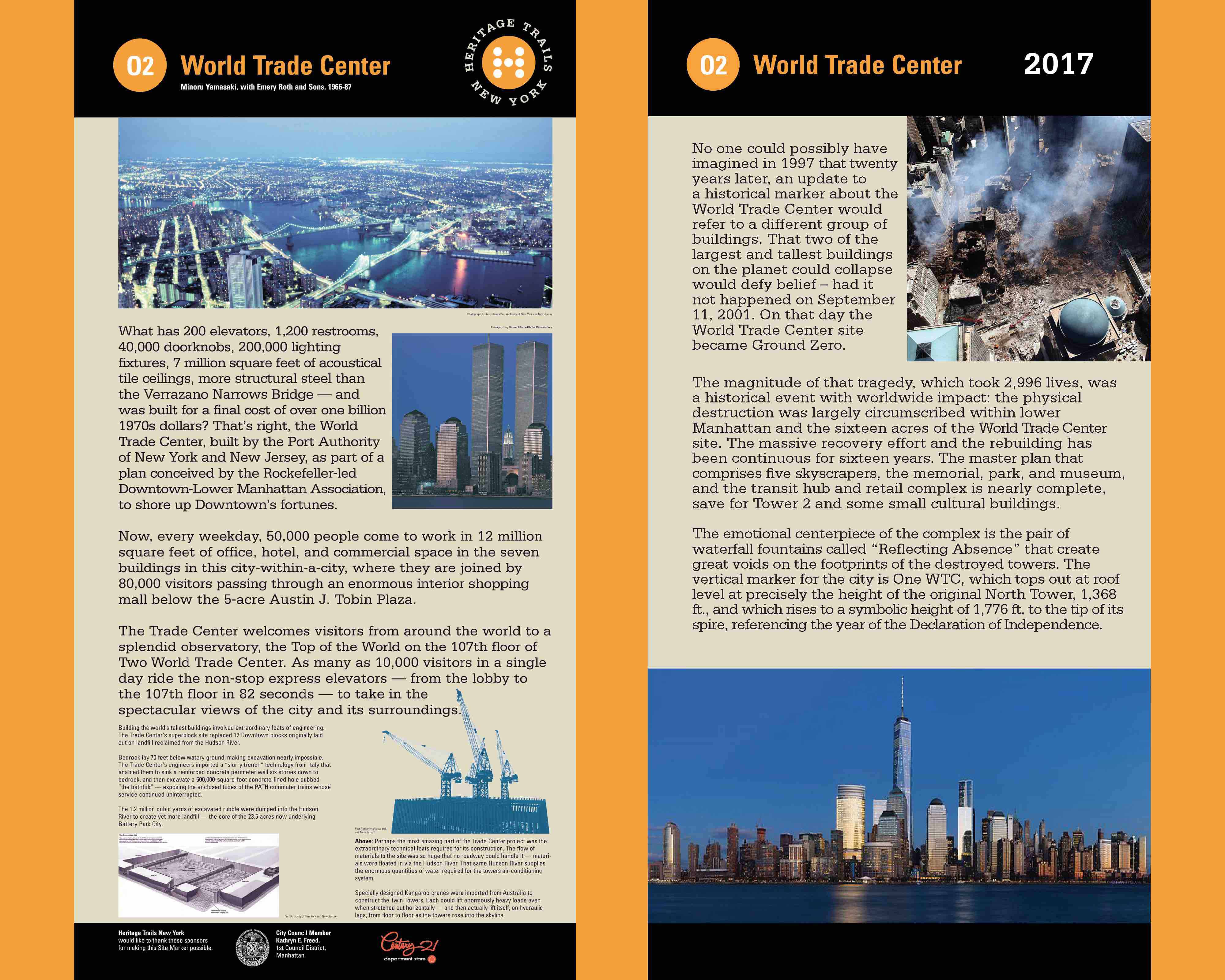

No one could possibly have imagined in 1997 that twenty years later, an update to a historical marker about the World Trade Center would refer to a different group of buildings. That two of the largest and tallest buildings on the planet could collapse would defy belief – had it not happened on September 11, 2001. On that day the World Trade Center site became Ground Zero. The magnitude of that tragedy, which took 2,996 lives, was a historical event with worldwide impact: the physical destruction was largely circumscribed within lower Manhattan and the sixteen acres of the World Trade Center site. The massive recovery effort and the rebuilding has been continuous for sixteen years. The master plan that comprises five skyscrapers, the memorial, park, and museum, and the transit hub and retail complex is nearly complete, save for Tower 2 and some small cultural buildings.

The emotional centerpiece of the complex is the pair of waterfall fountains called “Reflecting Absence” that create great voids on the footprints of the destroyed towers. The vertical marker for the city is One WTC, which tops out at roof level at precisely the height of the original North Tower, 1,368 ft., and which rises to a symbolic height of 1,776 ft. to the tip of its spire, referencing the year of the Declaration of Independence.

World Trade Center (1997)

What has 200 elevators, 1,200 restrooms, 40,000 doorknobs, 200,000 lighting fixtures, 7 million square feet of acoustical tile ceilings, more structural steel than the Verrazano Narrows Bridge — and was built for a final cost of over one billion 1970s dollars? That’s right, the World Trade Center, built by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, as part of a plan conceived by the Rockefeller-led Downtown-Lower Manhattan Association, to shore up Downtown’s fortunes.

Now, every weekday, 50,000 people come to work in 12 million square feet of office, hotel, and commercial space in the seven buildings in this city-within-a-city, where they are joined by 80,000 visitors passing through an enormous interior shopping mall below the 5-acre Austin J. Tobin Plaza.

The Trade Center welcomes visitors from around the world to a splendid observatory, the Top of the World on the 107th floor of Two World Trade Center. As many as 10,000 visitors in a single day ride the non-stop express elevators — from the lobby to the 107th floor in 82 seconds — to take in the spectacular views of the city and its surroundings.

Battery Park City

Battery Park City (2017)

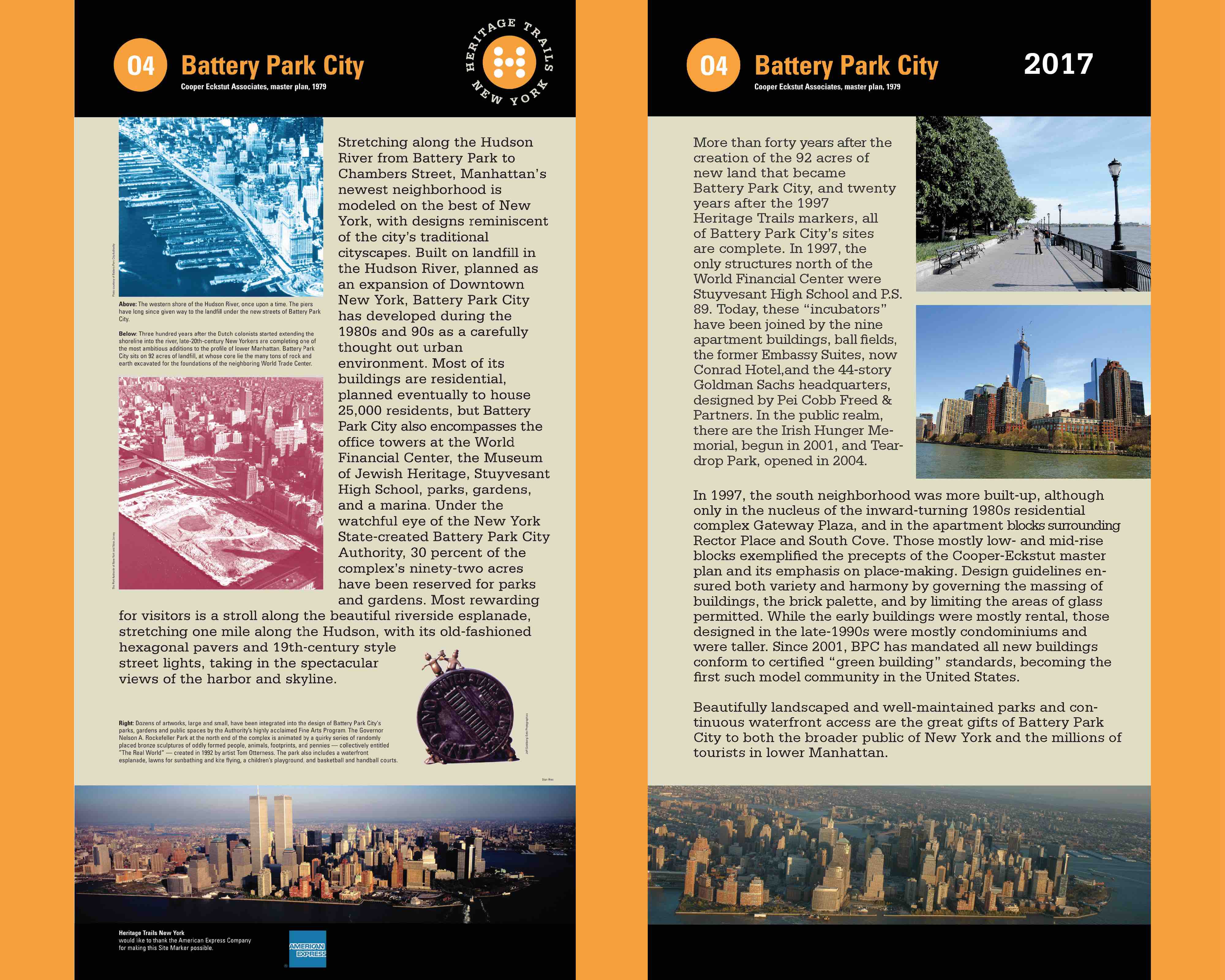

More than forty years after the creation of the 92 acres of new land that became Battery Park City, and twenty years after the 1997 Heritage Trails markers, all of Battery Park City’s sites are complete. In 1997, the only structures north of the World Financial Center were Stuyvesant High School and P.S. 89. Today, these “incubators” have been joined by the nine apartment buildings, ball fields, the former Embassy Suites, now Conrad Hotel, and the 44-story Goldman Sachs headquarters, designed by Pei Cobb Freed & Partners. In the public realm, there are the Irish Hunger Memorial, begun in 2001, and Teardrop Park, opened in 2004.

In 1997, the south neighborhood was more built-up, although only in the nucleus of the inward-turning 1980s residential complex Gateway Plaza, and in the apartment blocks surrounding Rector Place and South Cove. Those mostly low- and mid-rise blocks exemplified the precepts of the Cooper-Eckstut master plan and its emphasis on placemaking. Design guidelines ensured both variety and harmony by governing the massing of buildings, the brick palette, and by limiting the areas of glass permitted. While the early buildings were mostly rental, those designed in the late-1990s were mostly condominiums and were taller. Since 2001, BPC has mandated all new buildings conform to certified “green building” standards, becoming the first such model community in the United States.

Beautifully landscaped and well-maintained parks and continuous waterfront access are the great gifts of Battery Park City to both the broader public of New York and the millions of tourists in lower Manhattan.

Battery Park City (1997)

Stretching along the Hudson River from Battery Park to Chambers Street, Manhattan’s newest neighborhood is modeled on the best of New York, with designs reminiscent of the city’s traditional cityscapes. Built on landfill in the Hudson River, planned as an expansion of Downtown New York, Battery Park City has developed during the 1980s and 90s as a carefully thought out urban environment. Most of its buildings are residential, planned eventually to house 25,000 residents, but Battery Park City also encompasses the office towers at the World Financial Center, the Museum of Jewish Heritage, Stuyvesant High School, parks, gardens, and a marina. Under the watchful eye of the New York State-created Battery Park City Authority, 30 percent of the complex’s ninety-two acres have been reserved for parks and gardens. Most rewarding for visitors is a stroll along the beautiful riverside esplanade, stretching one mile along the Hudson, with its old-fashioned hexagonal pavers and 19th-century style street lights, taking in the spectacular views of the harbor and skyline.

World Financial Center

Brookfield Place (2017)

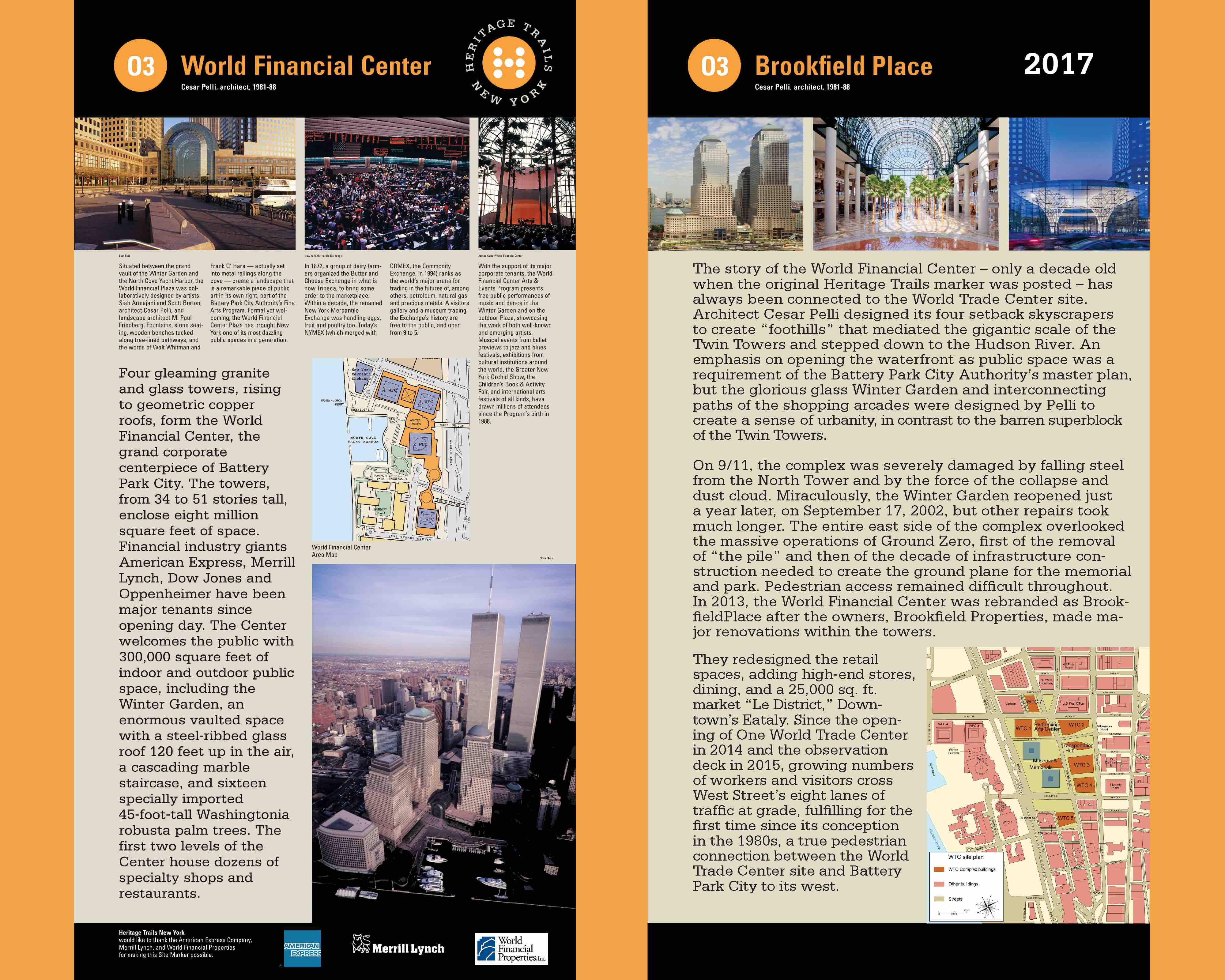

The story of the World Financial Center – only a decade old when the original Heritage Trails marker was posted – has always been connected to the World Trade Center site. Architect Cesar Pelli designed its four setback skyscrapers to create “foothills” that mediated the gigantic scale of the Twin Towers and stepped down to the Hudson River. An emphasis on opening the waterfront as public space was a requirement of the Battery Park City Authority’s master plan, but the glorious glass Winter Garden and interconnecting paths of the shopping arcades were designed by Pelli to create a sense of urbanity, in contrast to the barren superblock of the Twin Towers.

On 9/11, the complex was severely damaged by falling steel from the North Tower and by the force of the collapse and dust cloud. Miraculously, the Winter Garden reopened just a year later, on September 17, 2002, but other repairs took much longer. The entire east side of the complex overlooked the massive operations of Ground Zero, first of the removal of “the pile” and then of the decade of infrastructure construction needed to create the ground plane for the memorial and park. Pedestrian access remained difficult throughout.

In 2013, the World Financial Center was rebranded as Brookfield Place after the owners, Brookfield Properties, made major renovations within the towers. They redesigned the retail spaces, adding high-end stores, dining, and a 25,000 sq. ft. market “Le District,” Downtown’s Eataly. Since the opening of One World Trade Center in 2014 and the observation deck in 2015, growing numbers of workers and visitors cross West Street’s eight lanes of traffic at grade, fulfilling for the first time since its conception in the 1980s, a true pedestrian connection between the World Trade Center site and Battery Park City to its west.

World Financial Center (1997)

Four gleaming granite and glass towers, rising to geometric copper roofs, form the World Financial Center, the grand corporate centerpiece of Battery Park City. The towers, from 34 to 51 stories tall, enclose eight million square feet of space. Financial industry giants American Express, Merrill Lynch, Dow Jones and Oppenheimer have been major tenants since opening day. The Center welcomes the public with 300,000 square feet of indoor and outdoor public space, including the Winter Garden, an enormous vaulted space with a steel-ribbed glass roof 120 feet up in the air, a cascading marble staircase, and sixteen specially imported 45-foot-tall Washingtonia robusta palm trees. The first two levels of the Center house dozens of specialty shops and restaurants.

New York Stock Exchange

New York Stock Exchange (2017)

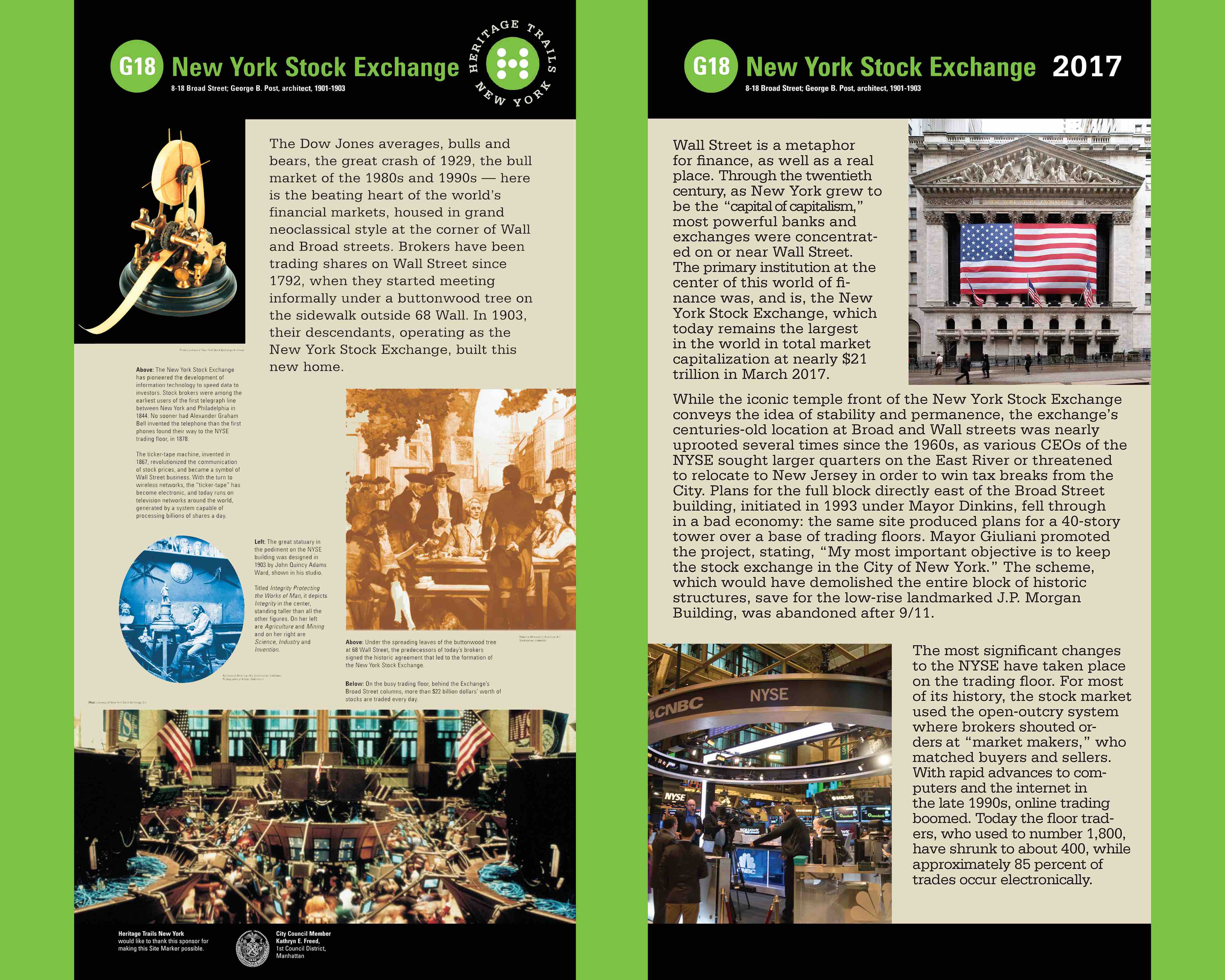

Wall Street is a metaphor for finance, as well as a real place. Through the twentieth century, as New York grew to be the “capital of capitalism,” most powerful banks and exchanges were concentrated on or near Wall Street. The primary institution at the center of this world of finance was, and is, the New York Stock Exchange, which today remains the largest in the world in total market capitalization at nearly $21 trillion in March 2017.

While the iconic temple front of the New York Stock Exchange conveys the idea of stability and permanence, the exchange’s centuries-old location at Broad and Wall streets was nearly uprooted several times since the 1960s, as various CEOs of the NYSE sought larger quarters on the East River or threatened to relocate to New Jersey in order to win tax breaks from the City. Plans for the full block directly east of the Broad Street building, initiated in 1993 under Mayor Dinkins, fell through in a bad economy: the same site produced plans for a 40-story tower over a base of trading floors. Mayor Giuliani promoted the project, stating, “My most important objective is to keep the stock exchange in the City of New York.” The scheme, which would have demolished the entire block of historic structures, save for the low-rise landmarked J.P. Morgan Building, was abandoned after 9/11.

The most significant changes to the NYSE have taken place on the trading floor. For most of its history, the stock market used the open-outcry system where brokers shouted orders at “market makers,” who matched buyers and sellers. With rapid advances to com-puters and the internet in the late 1990s, online trading boomed. Today the floor traders, who used to number 1,800, have shrunk to about 400, while approximately 85 percent of trades occur electronically.

New York Stock Exchange (1997)

The Dow Jones averages, bulls and bears, the great crash of 1929, the bull market of the 1980s and 1990s — here is the beating heart of the world’s financial markets, housed in grand neoclassical style at the corner of Wall and Broad streets. Brokers have been trading shares on Wall Street since 1792, when they started meeting informally under a buttonwood tree on the sidewalk outside 68 Wall. In 1903, their descendants, operating as the New York Stock Exchange, built this new home.

Federal Hall National Memorial

Federal Hall National Memorial (2017)

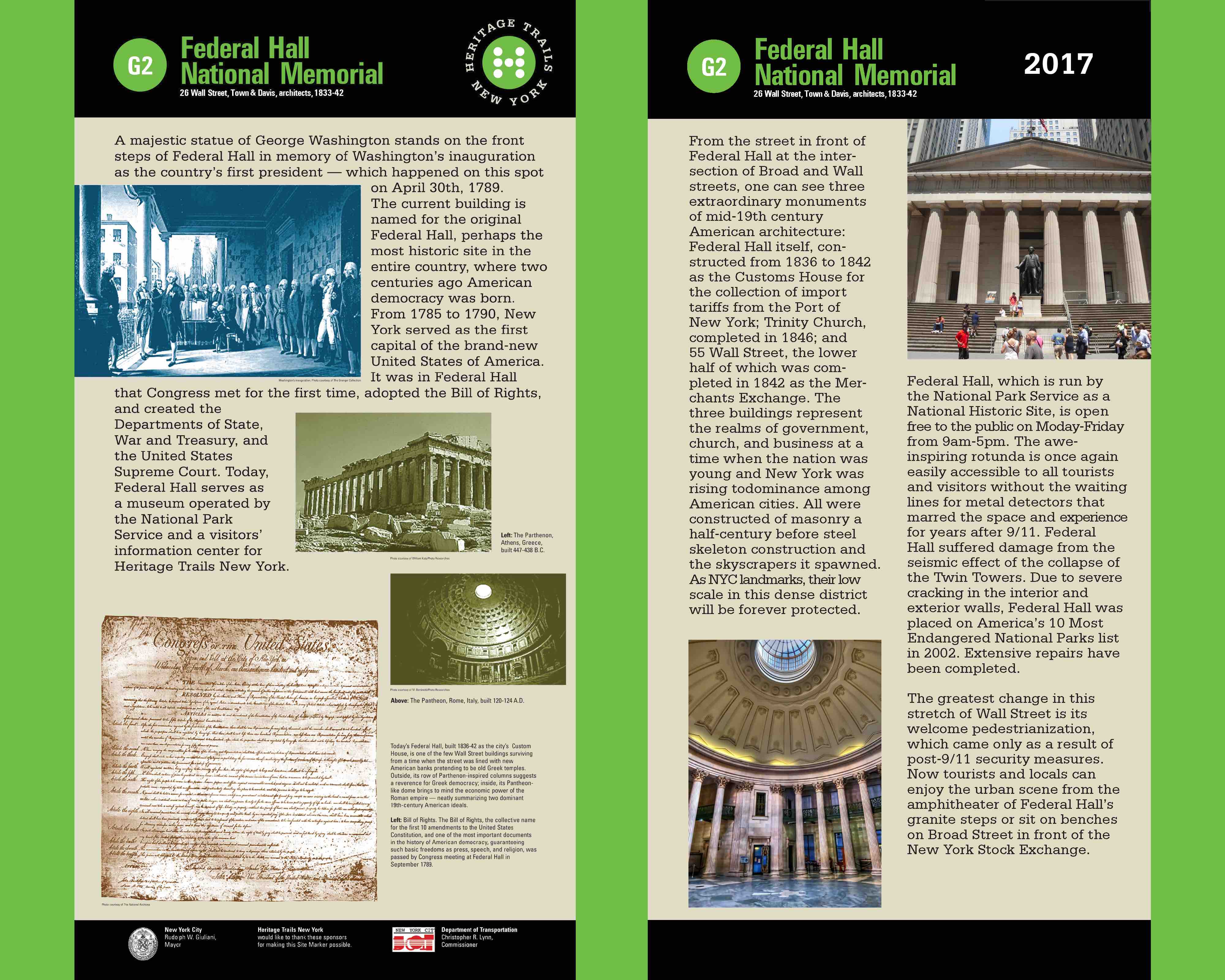

From the street in front of Federal Hall at the intersection of Broad and Wall streets, one can see three extraordinary monuments of mid-19th century American architecture: Federal Hall itself, constructed from 1836 to 1842 as the Customs House for the collection of import tariffs from the Port of New York; Trinity Church, completed in 1846; and 55 Wall Street, the lower half of which was completed in 1842 as the Merchants Exchange. The three buildings represent the realms of government, church, and business at a time when the nation was young and New York was rising to dominance among American cities. All were constructed of masonry a half-century before steel skeleton construction and the skyscrapers it spawned. As NYC landmarks, their low scale in this dense district will be forever protected.

Federal Hall, which is run by the National Park Service as a National Historic Site, is open free to the public on Monday-Friday from 9am-5pm. The awe-inspiring rotunda is once again easily accessible to all tourists and visitors without the waiting lines for metal detectors that marred the space and experience for years after 9/11. Federal Hall suffered damage from the seismic effect of the collapse of the Twin Towers. Due to severe cracking in the interior and exterior walls, Federal Hall was placed on America’s 10 Most Endangered National Parks list in 2002. Extensive repairs have been completed.

Federal Hall National Memorial (1997)

A majestic statue of George Washington stands on the front steps of Federal Hall in memory of Washington’s inauguration as the country’s first president — which happened on this spot on April 30th, 1789. The current building is named for the original Federal Hall, perhaps the most historic site in the entire country, where two centuries ago American democracy was born. From 1785 to 1790, New York served as the first capital of the brand-new United States of America. It was in Federal Hall that Congress met for the first time, adopted the Bill of Rights, and created the Departments of State, War and Treasury, and the United States Supreme Court. Today, Federal Hall serves as a museum operated by the National Park Service and a visitors’ information center for Heritage Trails New York.

14 Wall Street

14 Wall Street (2017)

In the 1990s, Wall Street– both the actual street and the financial service industry – was undergoing major changes. Banks were aggressively merging into national mega-banks, and when they did, they often left an empty tower down the block. Such was the case in 1988 when the Bank of New York left its 1929 tower at 48 Wall to merge with Irving Trust and consolidate in the sublime Art Deco headquarters at 1 Wall Street.

Designated a NYC landmark in 2001, the skyscraper remained a bank headquarters after the merger that created BNY Mellon in 2007. In 2014, the bank moved to the World Financial Center in Battery Park City, now renamed Brookfield Place.

The Art Deco landmark tower, along with its 1965 southern addition, was sold to a venture led by Macklowe Properties which has begun the conversion to luxury condominiums, joining the trend started in the mid-1990s of adapting historic office buildings to residential use. Nearly every high-rise on the south side of Wall Street from Broadway to Water Street has been converted into apartments. Plans by Robert A. M. Stern Architects for high-end condominiums will barely change the 1930 Ralph Walker tower, but several extra floors are being added to the roof of the 1965 addition.

14 Wall Street (1997)

On the world’s most expensive corners — 1 Wall Street and Broadway — architect Ralph Walker conceived his zig-zag Art Deco skyscraper for the Irving Trust Company as a “curtain wall” — not the typical sheet of glass hanging from a steel cage, but a limestone wall rippling like a curtain descending on a Broadway stage.

Because of the curves in the wall, the bank doesn’t completely occupy its full building lot, and by law unoccupied and unmarked land reverts to the public — not too many square inches are left unused here, but each one is worth gold. So a slender metal line in the sidewalk, with a small plaque at the corner, makes clear who owns what. Today it is the headquarters of the Bank of New York, which acquired Irving Trust in 1988.

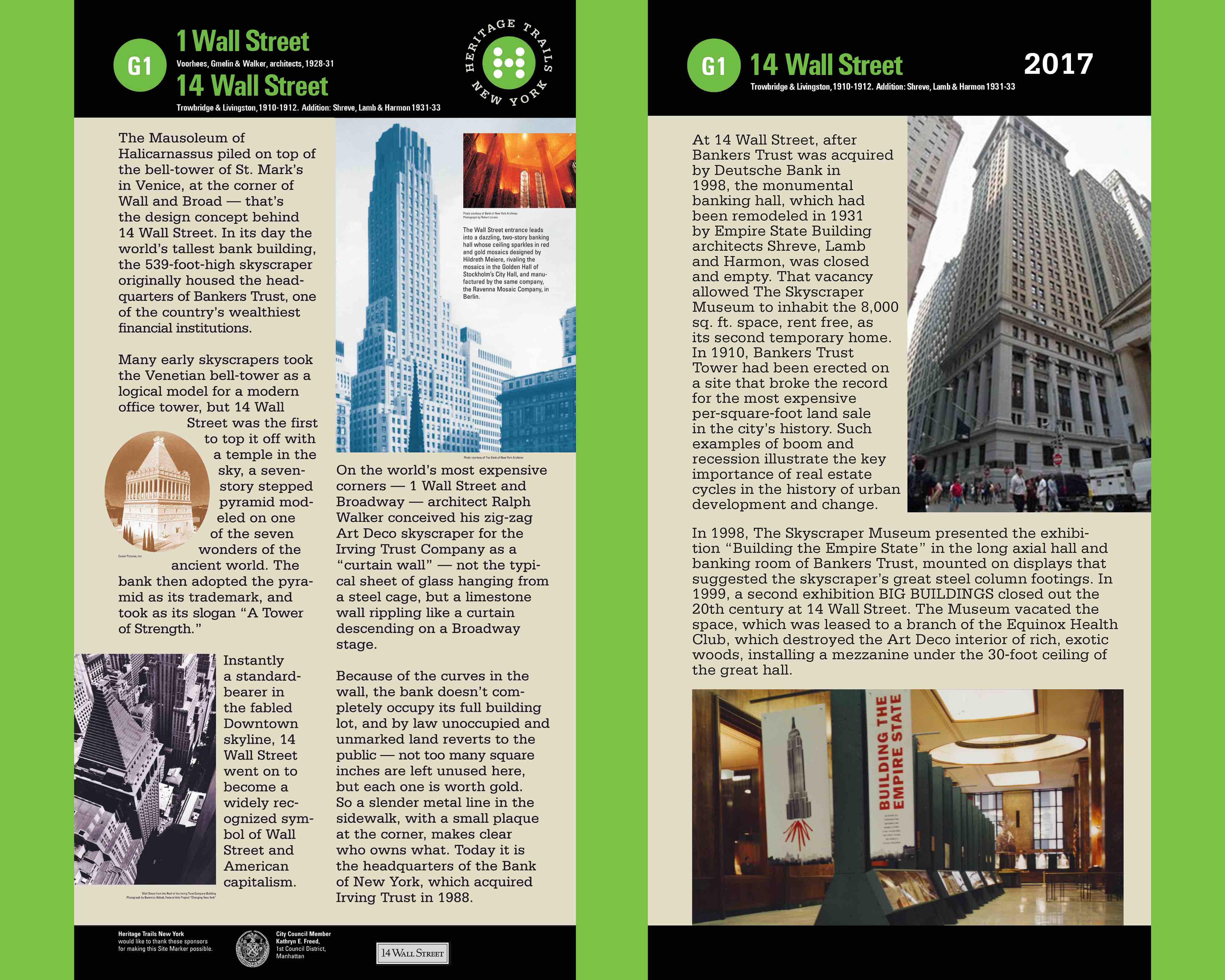

The Mausoleum of Halicarnassus piled on top of the bell-tower of St. Mark’s in Venice, at the corner of Wall and Broad — that’s the design concept behind 14 Wall Street. In its day the world’s tallest bank building, the 539-foot-high skyscraper originally housed the headquarters of Bankers Trust, one of the country’s wealthiest financial institutions.

Many early skyscrapers took the Venetian bell-tower as a logical model for a modern office tower, but 14 Wall Street was the first to top it off with a temple in the sky, a seven story stepped pyramid modeled on one of the seven wonders of the ancient world. The bank then adopted the pyramid as its trademark, and took as its slogan “A Tower of Strength.”

Instantly a standard bearer in the fabled Downtown skyline, 14 Wall Street went on to become a widely recognized symbol of Wall Street and American capitalism.

40 Wall Street & 48 Wall Street

40 Wall Street & 48 Wall Street (2017)

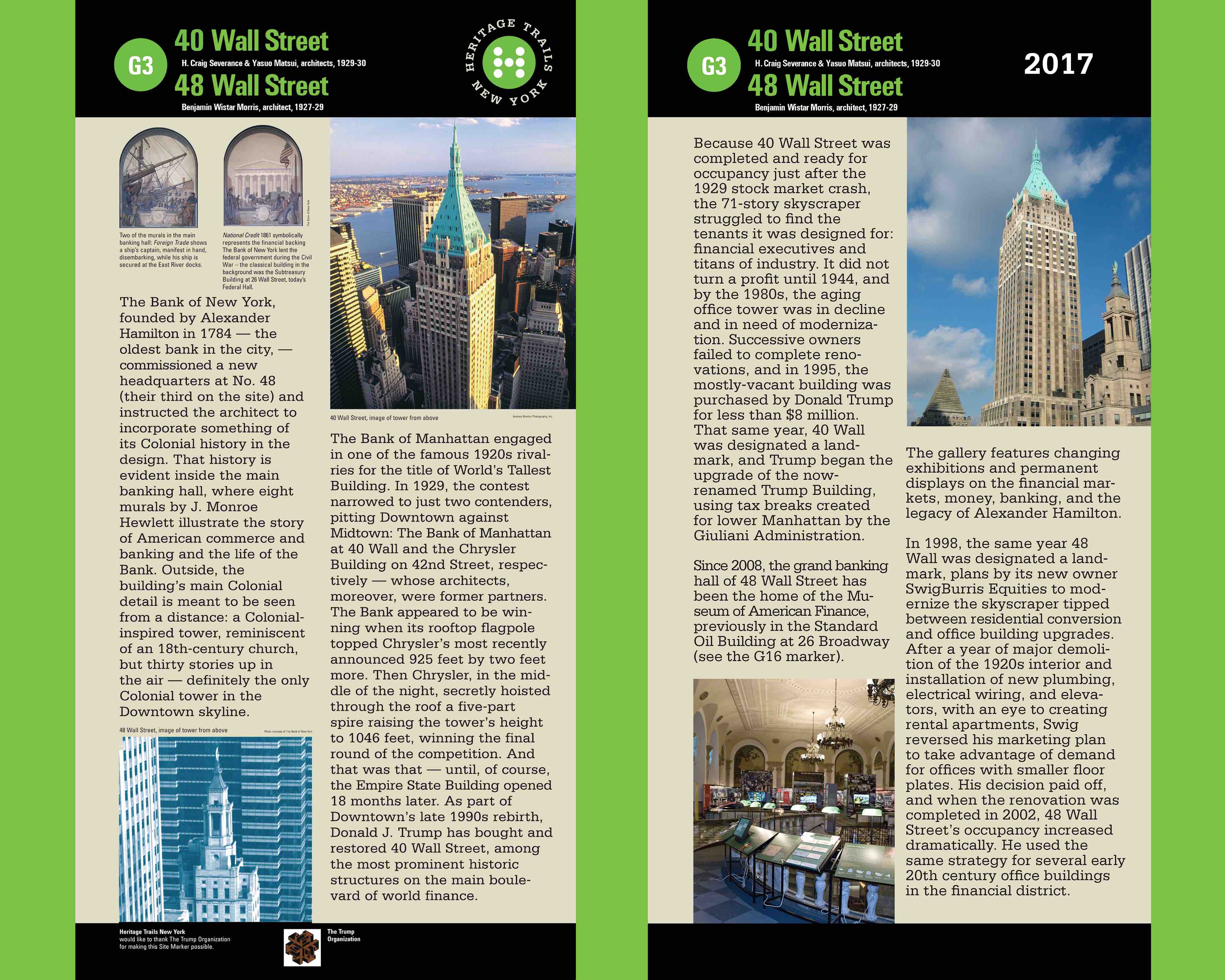

Because 40 Wall Street was completed and ready for occupancy just after the 1929 stock market crash, the 71-story skyscraper struggled to find the tenants it was designed for: financial executives and titans of industry. It did not turn a profit until 1944, and by the 1980s, the aging office tower was in decline and in need of modernization. Successive owners failed to complete renovations, and in 1995, the mostly-vacant building was purchased by Donald Trump for less than $8 million. That same year, 40 Wall was designated a landmark, and Trump began the upgrade of the now-renamed Trump Building, using tax breaks created for lower Manhattan by the Giuliani Administration.

Since 2008, the grand banking hall of 48 Wall Street has been the home of the Museum of American Finance, previously in the Standard Oil Building at 26 Broadway (see the G16 marker).

The gallery features changing exhibitions and permanent displays on the financial markets, money, banking, and the legacy of Alexander Hamilton.

In 1998, the same year 48 Wall was designated a landmark, plans by its new owner SwigBurris Equities to modernize the skyscraper tipped between residential conversion and office building upgrades. After a year of major demolition of the 1920s interior and installation of new plumbing, electrical wiring, and elevators, with an eye to creating rental apartments, Swig reversed his marketing plan to take advantage of demand for offices with smaller floor plates. His decision paid off, and when the renovation was completed in 2002, 48 Wall Street’s occupancy increased dramatically. He used the same strategy for several early 20th century office buildings in the financial district.

40 Wall Street & 48 Wall Street (1997) The Bank of New York, founded by Alexander Hamilton in 1784 — the oldest bank in the city, — commissioned a new headquarters at No. 48 (their third on the site) and instructed the architect to incorporate something of its Colonial history in the design. That history is evident inside the main banking hall, where eight murals by J. Monroe Hewlett illustrate the story of American commerce and banking and the life of the Bank. Outside, the building’s main Colonial detail is meant to be seen from a distance: a Colonial- inspired tower, reminiscent of an 18th-century church, but thirty stories up in the air — definitely the only Colonial tower in the Downtown skyline.

The Bank of Manhattan engaged in one of the famous 1920s rivalries for the title of World’s Tallest Building. In 1929, the contest narrowed to just two contenders, pitting Downtown against Midtown: The Bank of Manhattan at 40 Wall and the Chrysler Building on 42nd Street, respectively — whose architects, moreover, were former partners. The Bank appeared to be winning when its rooftop flagpole topped Chrysler’s most recently announced 925 feet by two feet more. Then Chrysler, in the middle of the night, secretly hoisted through the roof a five-part spire raising the tower’s height to 1046 feet, winning the final round of the competition. And that was that — until, of course, the Empire State Building opened 18 months later. As part of Downtown’s late 1990s rebirth, Donald J. Trump has bought and restored 40 Wall Street, among the most prominent historic structures on the main boulevard of world finance.

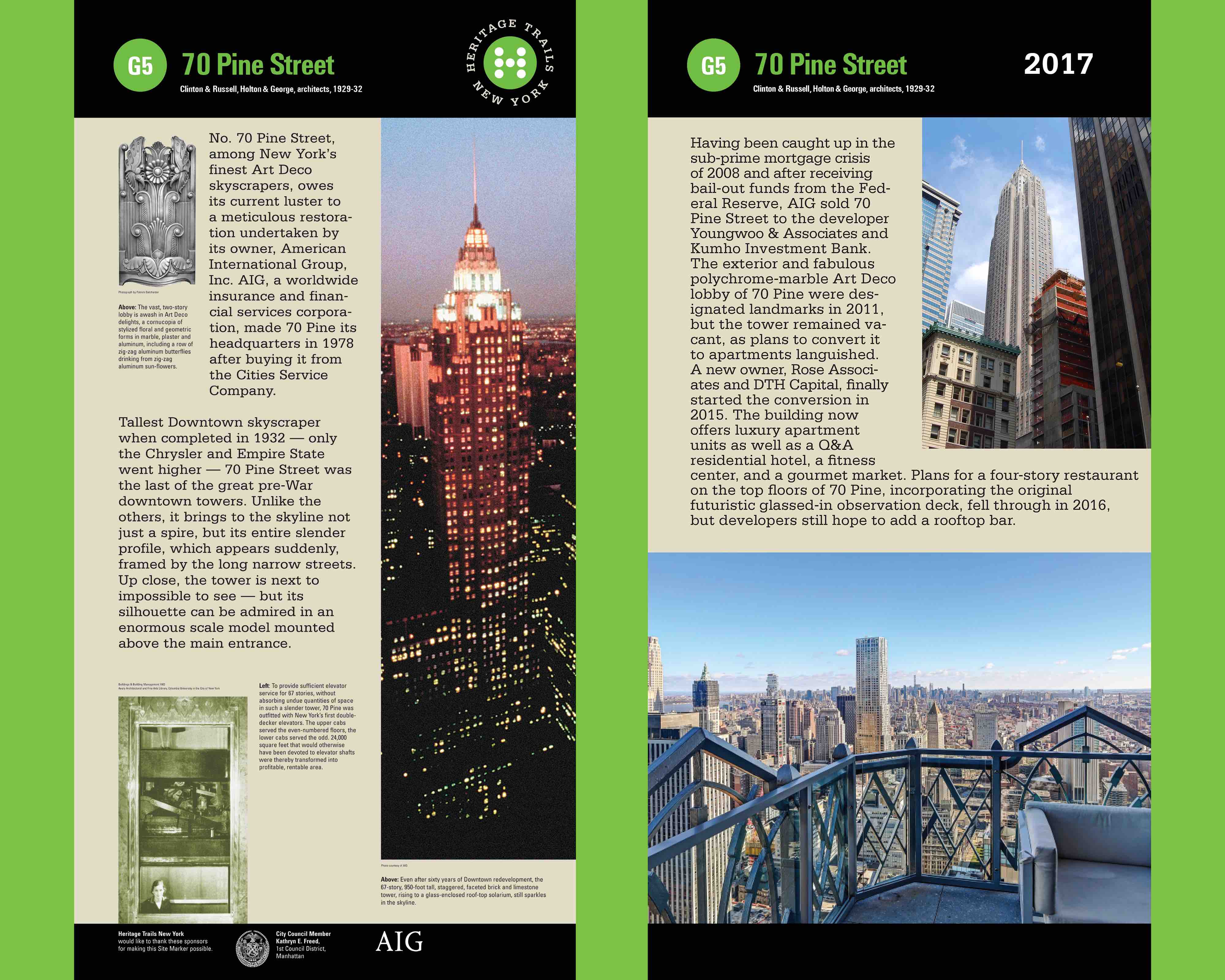

70 Pine Street

70 Pine Street 2017

Having been caught up in the sub-prime mortgage crisis of 2008 and after receiving bail-out funds from the Federal Reserve, AIG sold 70 Pine Street to the developer Youngwoo & Associates and Kumho Investment Bank. The exterior and fabulous polychrome-marble Art Deco lobby of 70 Pine were designated landmarks in 2011, but the tower remained vacant, as plans to convert it to apartments languished.

A new owner, Rose Associates and DTH Capital, finally started the conversion in 2015. The building now offers luxury apartment units as well as a Q&A residential hotel, a fitness center, and a gourmet market. Plans for a four-story restaurant on the top floors of 70 Pine, incorporating the original futuristic glassed-in observation deck, fell through in 2016, but developers still hope to add a rooftop bar.

70 Pine Street (1997)

No. 70 Pine Street, among New York’s finest Art Deco skyscrapers, owes its current luster to a meticulous restoration undertaken by its owner, American International Group, Inc. AIG, a worldwide insurance and financial services corporation, made 70 Pine its headquarters in 1978 after buying it from the Cities Service Company.

Tallest Downtown skyscraper when completed in 1932 — only the Chrysler and Empire State went higher — 70 Pine Street was the last of the great pre-War downtown towers. Unlike the others, it brings to the skyline not just a spire, but its entire slender profile, which appears suddenly, framed by the long narrow streets. Up close, the tower is next to impossible to see — but its silhouette can be admired in an enormous scale model mounted above the main entrance.

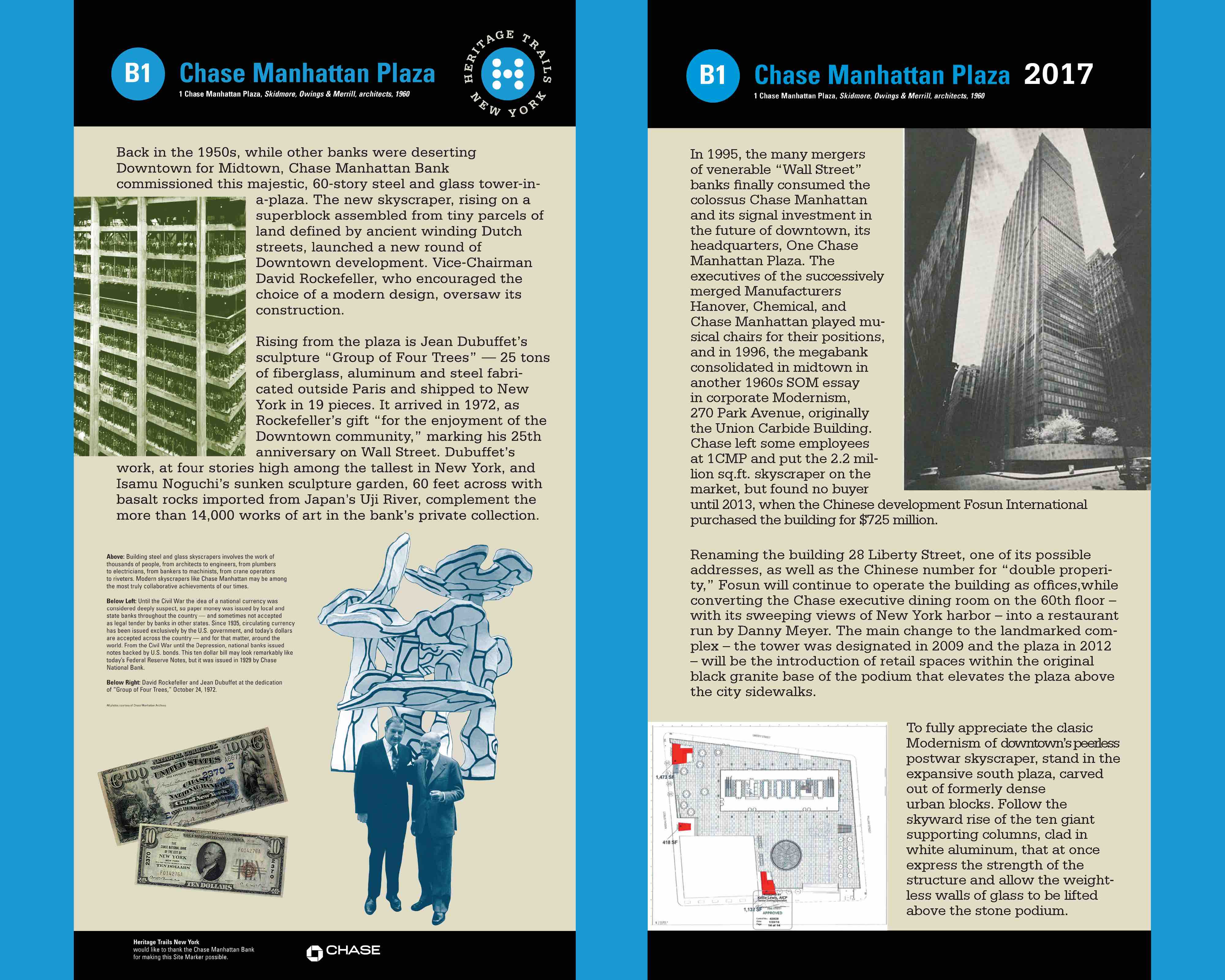

Chase Manhattan Plaza

Chase Manhattan Plaza (2017)

In 1995, the many mergers of venerable “Wall Street” banks finally consumed the colossus Chase Manhattan and its signal investment in the future of downtown, its headquarters, One Chase Manhattan Plaza. The executives of the successively merged Manufacturers Hanover, Chemical, and Chase Manhattan played musical chairs for their positions, and in 1996, the megabank consolidated in midtown in another 1960s SOM essay in corporate Modernism, 270 Park Avenue, originally the Union Carbide Building. Chase left some employees at 1 CMP and put the 2.2 million sq.ft. skyscraper on the market, but found no buyer until 2013, when the Chinese development company Fosun International purchased the building for $725 million.

Renaming the building 28 Liberty Street, one of its possible addresses, as well as the Chinese number for “double prosperity,” Fosun will continue to operate the building as offices, while converting the Chase executive dining room on the 60th floor – with its sweeping views of New York harbor – into a restaurant run by Danny Meyer. The main change to the landmarked complex – the tower was designated in 2009 and the plaza in 2012 – will be the introduction of retail spaces within the original black granite base of the podium that elevates the plaza above the city sidewalks.

To fully appreciate the classic Modernism of downtown’s peerless postwar skyscraper, stand in the expansive south plaza, carved out of formerly dense urban blocks. Follow the skyward rise of the ten giant supporting columns, clad in white aluminum, that at once express the strength of the structure and allow the weightless walls of glass to be lifted above the stone podium.

Chase Manhattan Plaza (1997) Back in the 1950s, while other banks were deserting Downtown for Midtown, Chase Manhattan Bank commissioned this majestic, 60-story steel and glass tower-in-a-plaza. The new skyscraper, rising on a superblock assembled from tiny parcels of land defined by ancient winding Dutch streets, launched a new round of Downtown development. Vice-Chairman David Rockefeller, who encouraged the choice of a modern design, oversaw its construction.

Rising from the plaza is Jean Dubuffet’s sculpture “Group of Four Trees” — 25 tons of fiberglass, aluminum and steel fabricated outside Paris and shipped to New York in 19 pieces. It arrived in 1972, as Rockefeller’s gift “for the enjoyment of the Downtown community,” marking his 25th anniversary on Wall Street. Dubuffet’s work, at four stories high among the tallest in New York, and Isamu Noguchi’s sunken sculpture garden, 60 feet across with basalt rocks imported from Japan’s Uji River, complement the more than 14,000 works of art in the bank’s private collection.

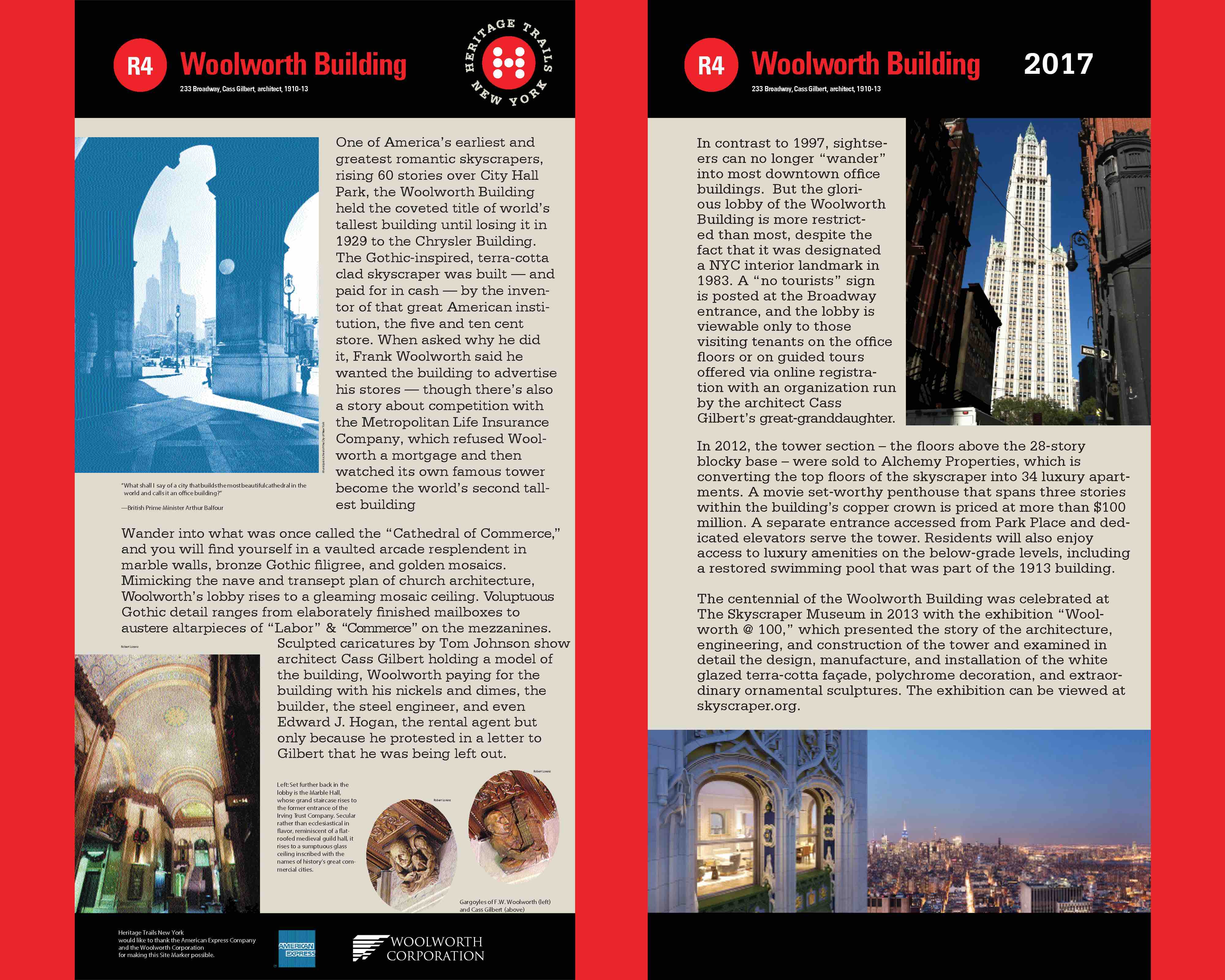

Woolworth Building

Woolworth Building (2017)

In contrast, to 1997, sightseers can no longer “wander” into most downtown office buildings. But the glorious lobby of the Woolworth Building is more restricted than most, despite the fact that it was designated a NYC interior landmark in 1983. A “no tourists” sign is posted at the Broadway entrance, and the lobby is viewable only to those visiting tenants on the office floors or on guided tours offered via online registration with an organization run by the architect Cass Gilbert’s great-granddaughter.

In 2012, the tower section – the floors above the 28-story blocky base – were sold to Alchemy Properties, which is converting the top floors of the skyscraper into 34 luxury apartments. A movie set-worthy penthouse that spans three stories within the building’s copper crown is priced at more than $100 million. A separate entrance accessed from Park Place and dedicated elevators serve the tower. Residents will also enjoy access to luxury amenities on the below-grade levels, including a restored swimming pool that was part of the 1913 building.

The centennial of the Woolworth Building was celebrated at The Skyscraper Museum in 2013 with the exhibition “Woolworth @ 100,” which presented the story of the architecture, engineering, and construction of the tower and examined in detail the design, manufacture, and installation of the white glazed terra-cotta façade, polychrome decoration, and extraordinary ornamental sculptures. The exhibition can be viewed at skyscraper.org.

Woolworth Building (1997)

One of America’s earliest and greatest romantic skyscrapers, rising 60 stories over City Hall Park, the Woolworth Building held the coveted title of world’s tallest building until losing it in 1929 to the Chrysler Building. The Gothic-inspired, terra-cotta clad skyscraper was built — and paid for in cash — by the inventor of that great American institution, the five and ten cent store. When asked why he did it, Frank Woolworth said he wanted the building to advertise his stores — though there’s also a story about competition with the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company, which refused Woolworth a mortgage and then watched its own famous tower become the world‘s second tallest building.

Wander into what was once called the “ Cathedral of Commerce, ” and you will find yourself in a vaulted arcade resplendent in marble walls, bronze Gothic filigree, and golden mosaics. Mimicking the nave and transept plan of church architecture, Woolworth’s lobby rises to a gleaming mosaic ceiling. Voluptuous Gothic detail ranges from elaborately finished mailboxes to austere altarpieces of “Labor” and “Commerce” on the mezzanines. Sculpted caricatures by Tom Johnson show architect Cass Gilbert holding a model of the building, Woolworth paying for the building with his nickels and dimes, the builder, the steel engineer, and even Edward J Hogan, the rental agent-but only because he protested in a letter to Gilbert that he was being left out.

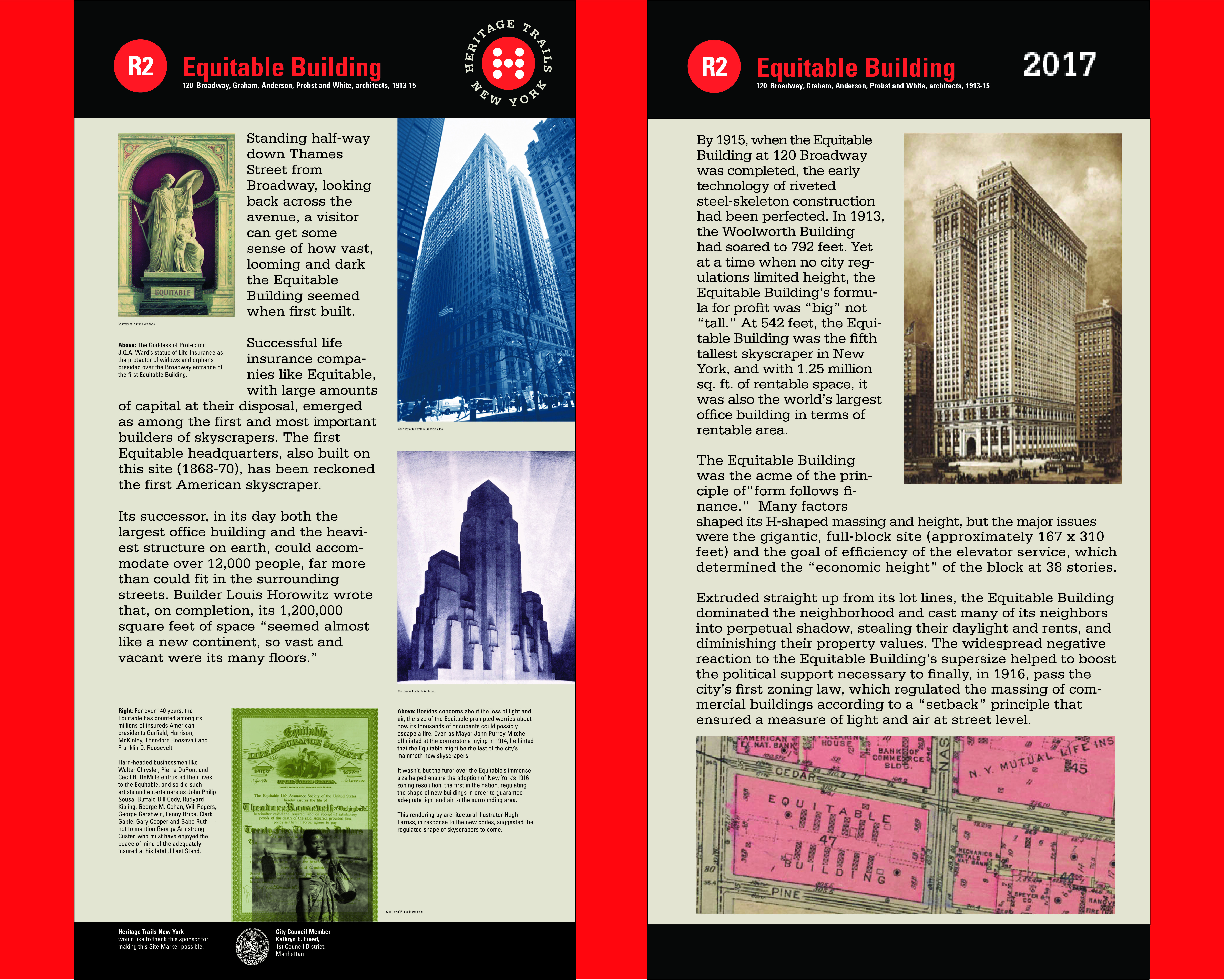

Equitable Building

Equitable Building (2017)

By 1915, when the Equitable Building at 120 Broadway was completed, the early technology of riveted steel-skeleton construction had been perfected. In 1913, the Woolworth Building had soared to 792 feet. Yet at a time when no city regulations limited height, the Equitable Building’s formula for profit was “big” not “tall.” At 542 feet, the Equitable Building was the fifth tallest skyscraper in New York, and with 1.25 million sq. ft. of rentable space, it was also the world’s largest office building in terms of rentable area.

The Equitable Building was the acme of the principle of “form follows finance.” Many factors shaped its H-shaped massing and height, but the major issues were the gigantic, full-block site (approximately 167 x 310 feet) and the goal of efficiency of the elevator service, which determined the “economic height” of the block at 38 stories.

Extruded straight up from its lot lines, the Equitable Building dominated the neighborhood and cast many of its neighbors into perpetual shadow, stealing their daylight and rents, and diminishing their property values. The widespread negative reaction to the Equitable Building’s supersize helped to boost the political support necessary to finally, in 1916, pass the city’s first zoning law, which regulated the massing of commercial buildings according to a “setback” principle that ensured a measure of light and air at street level.

Equitable Building (1997)

Standing half-way down Thames Street from Broadway, looking back across the avenue, a visitor can get some sense of how vast, looming and dark the Equitable Building seemed when first built.

Successful life insurance companies like Equitable, with large amounts of capital at their disposal, emerged as among the first and most important builders of skyscrapers. The first Equitable headquarters, also built on this site (1868-70), has been reckoned the first American skyscraper.

Its successor, in its day both the largest office building and the heaviest structure on earth, could accommodate over 12,000 people, far more than could fit in the surrounding streets. Builder Louis Horowitz wrote that, on completion, its 1,200,000 square feet of space “seemed almost like a new continent, so vast and vacant were its many floors.”

Pier 17, Fulton Fish Market

Pier 17, Fulton Fish Market (2017)

After 180 years of operation in lower Manhattan, the historic Fulton Fish Market closed on November 11, 2005 after a long government campaign to break the hold of organized crime that had ruled the market for decades. The location on South Street at the East River end of Fulton Street had been the home to a succession of markets and buildings since 1822. With its location right on the wharves, Fulton Market was ideal for unloading boats and selling fresh fish. A wood market hall erected in 1869 was replaced in 1907 by the “Tin Building.” That landmarked structure is being restored as part of the Howard Hughes Corp. redevelopment of the Seaport and will be adaptively reused as restaurants and retail.

Racketeering plagued the market throughout the twentieth century, but was largely ignored by authorities. Prominent gangster Joseph “Socks” Lanza famously ruled over Fulton Fish Market from the 1920s until his death in 1968. In 1985, as the U.S. District Attorney, Rudolph Giuliani led his first campaign to rid the market of the Mob, and he continued in 1995 as mayor. A first-come, first-serve system for unloading trucks was instituted, and resisted; in 1995, the Tin Building was nearly destroyed by arsonists. The clean-up was ultimately successful, and in 1999, The New York Times declared,“organized crime rackets appear to have been eliminated.”

Still, the Fulton Fish Market moved from Lower Manhattan to Hunts Point in the Bronx in 2005, joining the produce market in modern facilities with refrigeration and ample room for trucks.

Pier 17, Fulton Fish Market (1997)

From South Street Seaport, the pungent odor of fish leads into another world, the ramshackle collection of buildings housing New York’s famous Fulton Fish Market, founded in the early 19th century. In the early hours of the morning, emissaries from restaurants throughout the city arrive in search of the day’s fresh catch.

Tucked between the Market stalls and the Seaport’s historic ships, Pier 17 stretches well out into the East River, where the Market’s fishy smell disappears.

The three-story glass and steel pavilion on a newly built pier forms part of The Rouse Company’s South Street Seaport. The urban marketplace houses shops and restaurants of every description.

In nice weather, visitors can walk up the outside staircases to the upper level, stretch out on a deck chair, and feel like they’ve landed a berth on an ocean liner — enjoying Downtown’s famous silhouette, views of the bridges up river, the Brooklyn port down river, and Brooklyn Heights beckoning on the opposite shore.

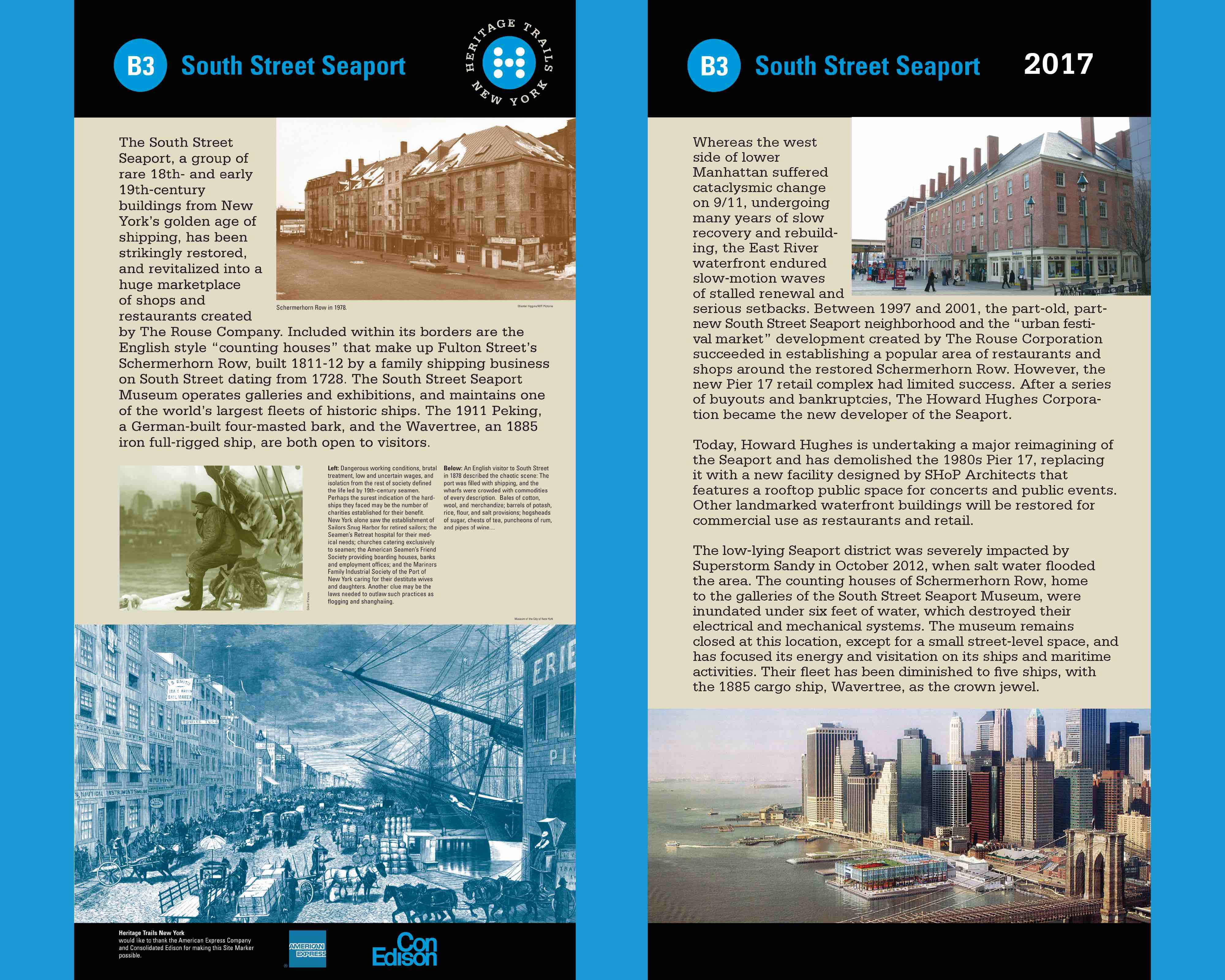

South Street Seaport

South Street Seaport (2017)

Whereas the west side of lower Manhattan suffered cataclysmic change on 9/11, undergoing many years of slow recovery and rebuilding, the East River waterfront endured slow-motion waves of stalled renewal and serious setbacks. Between 1997 and 2001, the part-old, part-new South Street Seaport neighborhood and the “urban festival market” development created by The Rouse Corporation succeeded in establishing a popular area of restaurants and shops around the restored Schermerhorn Row. However, the new Pier 17 retail complex had limited success. After a series of buyouts and bankruptcies, The Howard Hughes Corporation became the new developer of the Seaport.

Today, Howard Hughes is undertaking a major reimagining of the Seaport and has demolished the 1980s Pier 17, replacing it with a new facility designed by SHoP Architects that features a rooftop public space for concerts and public events. Other landmarked waterfront buildings will be restored for commercial use as restaurants and retail.

The low-lying Seaport district was severely impacted by Superstorm Sandy in October 2012, when salt water flooded the area. The counting houses of Schermerhorn Row, home to the galleries of the South Street Seaport Museum, were inundated under six feet of water, which destroyed their electrical and mechanical systems. The museum remains closed at this location, except for a small street-level space, and has focused its energy and visitation on its ships and maritime activities. Their fleet has been diminished to five ships, with the 1885 cargo ship, Wavertree, as the crown jewel.

South Street Seaport (1997)

The South Street Seaport, a group of rare 18th- and early 19th-century buildings from New York’s golden age of shipping, has been strikingly restored, and revitalized into a huge marketplace of shops and restaurants created by The Rouse Company. Included within its borders are the English style “counting houses” that make up Fulton Street’s Schermerhorn Row, built 1811-12 by a family shipping business on South Street dating from 1728. The South Street Seaport Museum operates galleries and exhibitions, and maintains one of the world’s largest fleets of historic ships. The 1911 Peking, a German-built four-masted bark, and the Wavertree, an 1885 iron full-rigged ship, are both open to visitors.

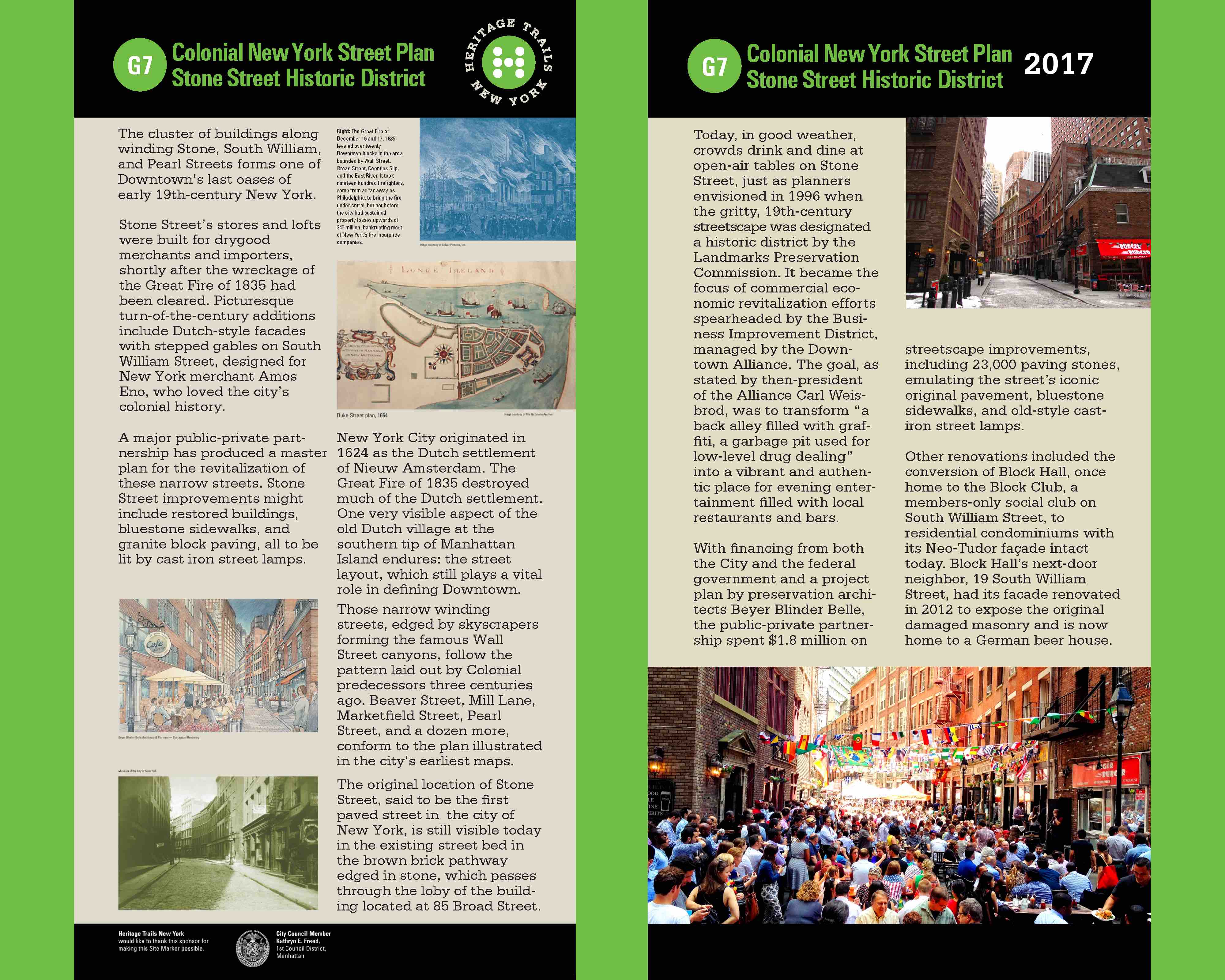

Colonial New York Street Plan, Stone Street Historic District

Colonial New York Street Plan, Stone Street Historic District (2017)

Today, in good weather, crowds drink and dine at open-air tables on Stone Street, just as planners envisioned in 1996 when the gritty, 19th-century streetscape was designated a historic district by the Landmarks Preservation Commission. It became the focus of commercial economic revitalization efforts spearheaded by the Business Improvement District, managed by the Downtown Alliance. The goal, as stated by then-president of the Alliance Carl Weisbrod, was to transform “a back alley filled with graffiti, a garbage pit used for low-level drug dealing” into a vibrant and authentic place for evening entertainment filled with local restaurants and bars.

With financing from both the City and the federal government and a project plan by preservation architects Beyer Blinder Belle, the public-private partnership spent $1.8 million on streetscape improvements, including 23,000 paving stones, emulating the street’s iconic original pavement, bluestone sidewalks, and old-style cast- iron street lamps.

Other renovations included the conversion of Block Hall, once home to the Block Club, a members-only social club on South William Street, to residential condominiums with its Neo-Tudor façade intact today. Block Hall’s next-door neighbor, 19 South William Street, had its facade renovated in 2012 to expose the original damaged masonry and is now home to a German beer house.

Colonial New York Street Plan, Stone Street Historic District (1997)

New York City originated in 1624 as the Dutch settlement of Nieuw Amsterdam. The Great Fire of 1835 destroyed much of the Dutch settlement. One very visible aspect of the old Dutch village at the southern tip of Manhattan Island endures: the street layout, which still plays a vital role in defining Downtown.

Those narrow, winding streets, edged by skyscrapers forming the famous Wall Street canyons, follow the pattern laid out by Colonial predecessors three centuries ago. Beaver Street, Mill Lane, Marketfield Street, Pearl Street, and a dozen more, conform to the plan illustrated in the city’s earliest maps.

The original location of Stone Street, said to be the first paved street in the city of New York, is still visible today in the existing street bed and in the brown brick pathway, edged in stone, which passes through the lobby of the building located at 85 Broad Street.

The cluster of buildings along winding Stone, South William and Pearl Streets forms one of Downtown’s last oases of early 19th-century New York.

Stone Street’s stores and lofts were built for dry good merchants and importers, shortly after the wreckage of the Great Fire of 1835 had been cleared. Picturesque turn-of- the-century additions include Dutch-style facades with stepped gables on South William Street, designed for New York merchant Amos Eno, who loved the city’s colonial history.

A major public-private partnership has produced a master plan for the revitalization of these narrow streets. Stone Street improvements might include restored buildings, bluestone sidewalks, and granite block paving, all to be lit by cast-iron street lamps.

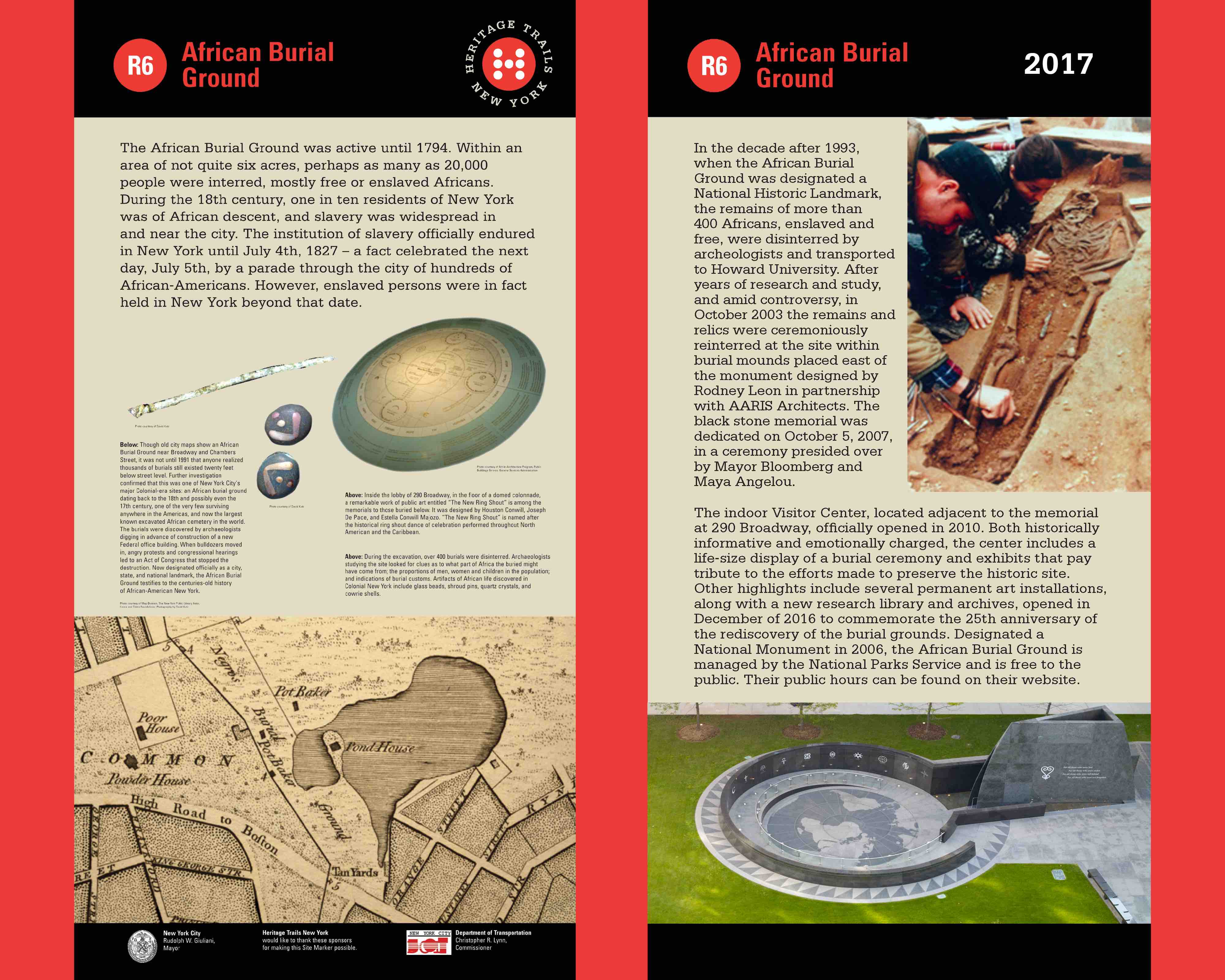

African Burial Ground

African Burial Ground (2017)

In the decade after 1993, when the African Burial Ground was designated a National Historic Landmark, the remains of more than 400 Africans, enslaved and free, were disinterred by archeologists and transported to Howard University. After years of research and study, and amid controversy, in October 2003 the remains and relics were ceremoniously reinterred at the site within burial mounds placed east of the monument designed by Rodney Leon in partnership with AARIS Architects. The black stone memorial was dedicated on October 5, 2007, in a ceremony presided over by Mayor Bloomberg and Maya Angelou.

The indoor Visitor Center, located adjacent to the memorial at 290 Broadway, officially opened in 2010. Both historically informative and emotionally charged, the center includes a life-size display of a burial ceremony and exhibits that pay tribute to the efforts made to preserve the historic site. Other highlights include several permanent art installations, along with a new research library and archives, opened in December of 2016 to commemorate the 25th anniversary of the rediscovery of the burial grounds. Designated a National Monument in 2006, the African Burial Ground is managed by the National Parks Service and is free to the public. Their public hours can be found on their website.

African Burial Ground (1997)

The African Burial Ground was active until 1794. Within an area of not quite six acres, perhaps as many as 20,000 people were interred, mostly free or enslaved Africans. During the 18th century, one in ten residents of New York was of African descent, and slavery was widespread in and near the city. The institution of slavery officially endured in New York until July 4th, 1827 – a fact celebrated the next day, July 5th, by a parade through the city of hundreds of African- Americans. However, enslaved persons were in fact held in New York beyond that date.

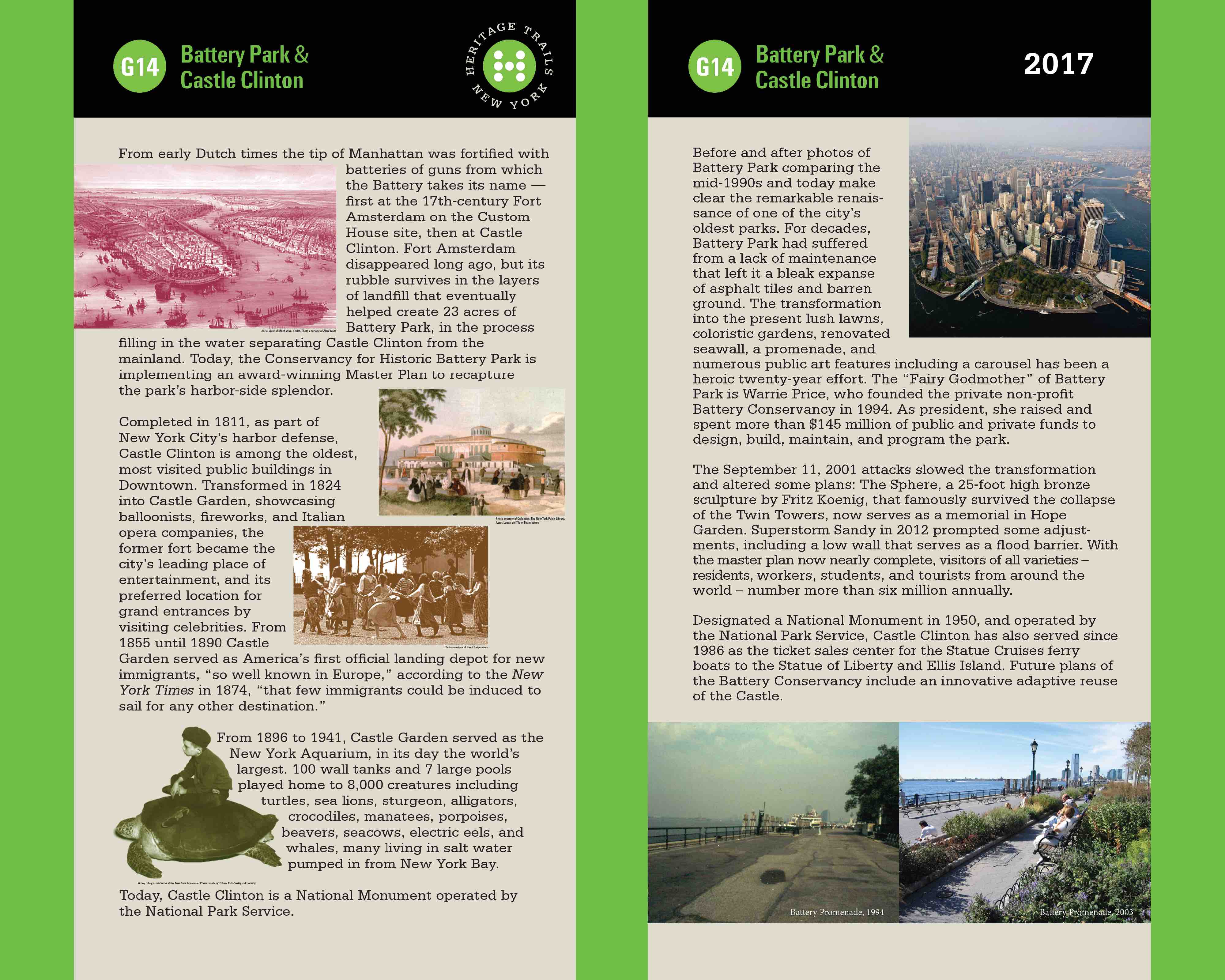

Historic Battery Park & Castle Clinton

Historic Battery Park & Castle Clinton (2017)

Before and after photos of Battery Park comparing the mid-1990s and today make clear the remarkable renaissance of one of the city’s oldest parks. For decades, Battery Park had suffered from a lack of maintenance that left it a bleak expanse of asphalt tiles and barren ground. The transformation into the present lush lawns, coloristic gardens, renovated seawall, a promenade, and numerous public art features including a carousel has been a heroic twenty-year effort. The “Fairy Godmother” of Battery Park is Warrie Price, who founded the private nonprofit Battery Conservancy in 1994. As president, she raised and spent more than $145 million of public and private funds to design, build, maintain, and program the park.

The September 11, 2001 attacks slowed the transformation and altered some plans: The Sphere, a 25-foot high bronze sculpture by Fritz Koenig, that famously survived the collapse of the Twin Towers, now serves as a memorial in Hope Garden. Superstorm Sandy in 2012 prompted some adjustments, including a low wall that serves as a flood barrier. With the master plan now nearly complete, visitors of all varieties – residents, workers, students, and tourists from around the world – number more than six million annually.

Designated a National Monument in 1950, and operated by the National Park Service, Castle Clinton has also served since 1986 as the ticket sales center for the Statue Cruises ferry boats to the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island. Future plans of the Battery Conservancy include an innovative adaptive reuse of the Castle.

Battery Park & Castle Clinton (1997)

From early Dutch times the tip of Manhattan was fortified with batteries of guns from which the Battery takes its name — first at the 17th-century Fort Amsterdam on the Custom House site, then at Castle Clinton. Fort Amsterdam disappeared long ago, but its rubble survives in the layers of landfill that eventually helped create 23 acres of Battery Park, in the process filling in the water separating Castle Clinton from the mainland. Today, the Conservancy for Historic Battery Park is implementing an award-winning Master Plan to recapture the park’s harbor-side splendor.

Completed in 1811, as part of New York City’s harbor defense, Castle Clinton is among the oldest, most visited public buildings in Downtown. Transformed in 1824 into Castle Garden, showcasing balloonists, fireworks, and Italian opera companies, the for mer fort became the city’s leading place of entertainment, and its preferred location for grand entrances by visiting celebrities. From 1855 until 1890 Castle Garden served as America’s first official landing depot for new immigrants, “so well known in Europe,” according to the New York Times in 1874, “that few immigrants could be induced to sail for any other destination.”

From 1896 to 1941, Castle Garden served as the New York Aquarium, in its day the world’s largest. 100 wall tanks and 7 large pools played home to 8,000 creatures including turtles, sea lions, sturgeon, alligators, crocodiles, manatees, porpoises, beavers, seacows, electric eels, and whales, many living in salt water pumped in from New York Bay.

Today, Castle Clinton is a National Monument operated by the National Park Service.

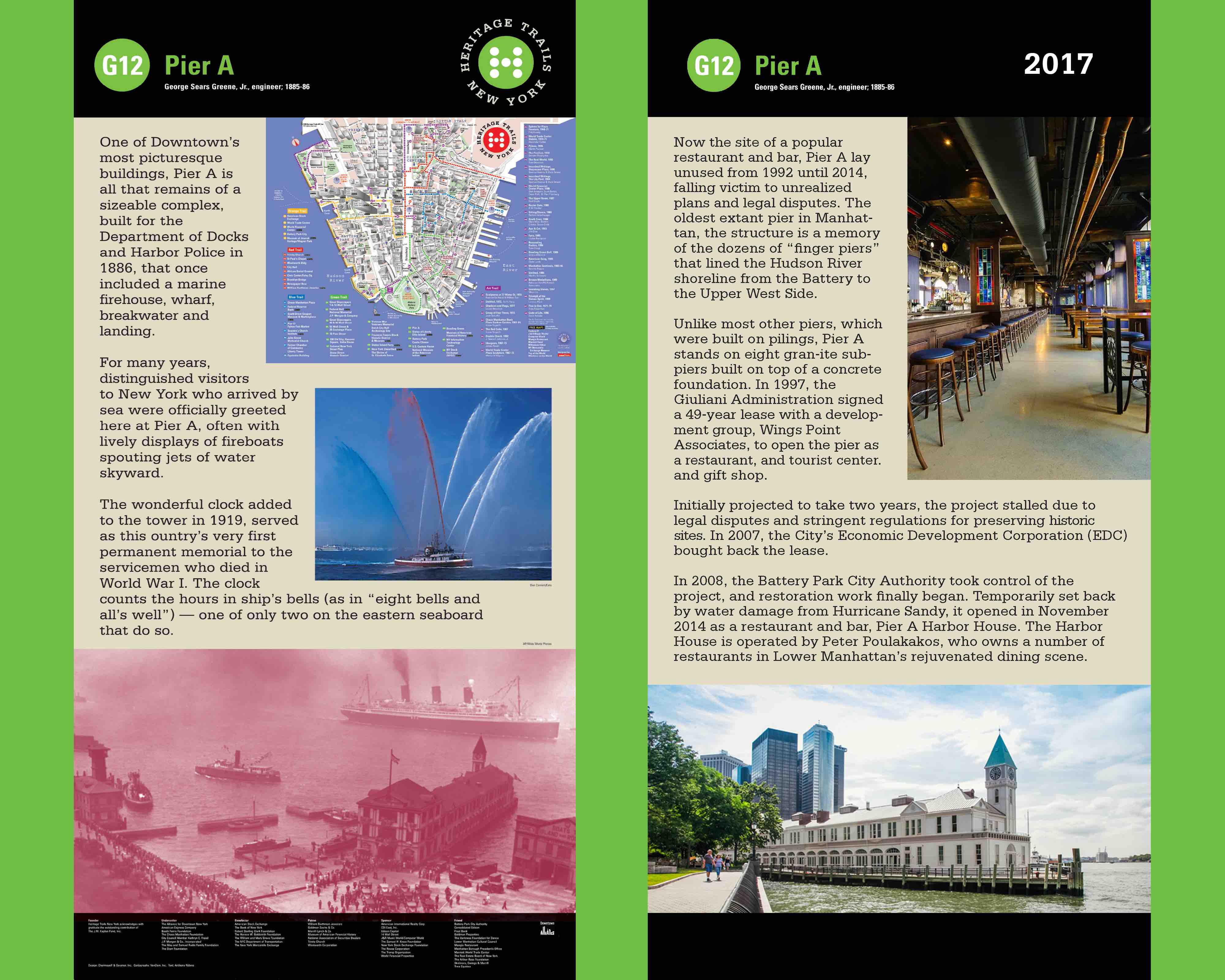

Pier A

Pier A (2017)

Now the site of a popular restaurant and bar, Pier A lay unused from 1992 until 2014, falling victim to unrealized plans and legal disputes. The oldest extant pier in Manhattan, the structure is a memory of the dozens of “finger piers” that lined the Hudson River shoreline from the Battery to the Upper West Side.

Unlike most other piers, which were built on pilings, Pier A stands on eight granite sub-piers built on top of a concrete foundation. In 1997, the Giuliani Administration signed a 49-year lease with a development group, Wings Point Associates, to open the pier as a restaurant, and tourist center. Projected to take two years, the project stalled due to legal disputes and stringent regulations for preserving historic sites. In 2007, the City’s Economic Development Corporation (EDC) bought back the lease.

In 2008, the Battery Park City Authority took control of the project, and restoration work finally began. Temporarily set back by water damage from Hurricane Sandy, it opened in November 2014 as a restaurant and bar, Pier A Harbor House. The Harbor House is operated by Peter Poulakakos, who owns a number of restaurants in Lower Manhattan’s rejuvenated dining scene.

Pier A (1997)

One of Downtown’s most picturesque buildings, Pier A is all that remains of a sizeable complex, built for the Department of Docks and Harbor Police in 1886, that once included a marine firehouse, wharf, breakwater and landing.

For many years, distinguished visitors to New York who arrived by sea were officially greeted here at Pier A, often with lively displays of fireboats spouting jets of water skyward.

The wonderful clock added to the tower in 1919, served as this country’s very first permanent memorial to the servicemen who died in World War I. The clock counts the hours in ship’s bells (as in “eight bells and all’s well”) — one of only two on the eastern seaboard that do so.

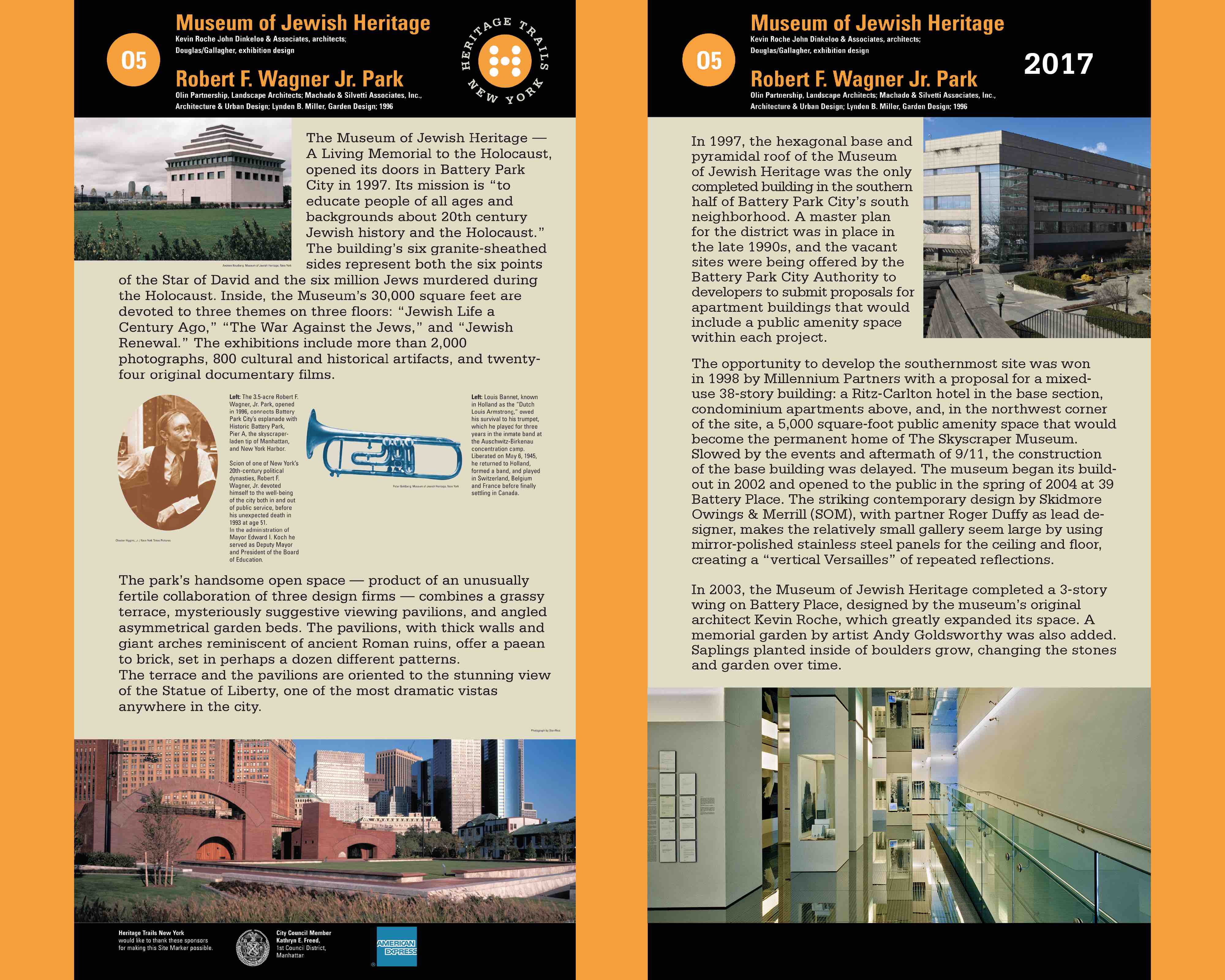

Museum of Jewish Heritage, Robert F. Wagner Jr. Park, The Skyscraper Museum

Museum of Jewish Heritage, Robert F. Wagner Jr. Park (2017)

In 1997, the hexagonal base and pyramidal roof of the Museum of Jewish Heritage was the only completed building in the southern half of Battery Park City’s south neighborhood. A master plan for the district was in place in the late 1990s, and the vacant sites were being offered by the Battery Park City Authority to developers to submit proposals for apartment buildings that would include a public amenity space within each project.

The opportunity to develop the southernmost site was won in 1998 by Millennium Partners with a proposal for a mixed-use 38-story building: a Ritz-Carlton hotel in the base section, condominium apartments above, and, in the northwest corner of the site, a 5,000 square-foot public amenity space that would become the permanent home of The Skyscraper Museum. Slowed by the events and aftermath of 9/11, the construction of the base building was delayed. The museum began its build-out in 2002 and opened to the public in the spring of 2004 at 39 Battery Place. The striking contemporary design by Skidmore Owings & Merrill (SOM), with partner Roger Duffy as lead designer, makes the relatively small gallery seem large by using mirror-polished stainless steel panels for the ceiling and floor, creating a “vertical Versailles” of repeated reflections.

In 2003, the Museum of Jewish Heritage completed a 3-story wing on Battery Place, designed by the museum’s original architect Kevin Roche, which greatly expanded its space. A memorial garden by artist Andy Goldsworthy was also added. Saplings planted inside of boulders grow, changing the stones and garden over time.

Museum of Jewish Heritage, Robert F. Wagner Jr. Park (1997)

The Museum of Jewish Heritage — A Living Memorial to the Holocaust, opened its doors in Battery Park City in 1997. Its mission is “to educate people of all ages and backgrounds about 20th century Jewish history and the Holocaust.” The building’s six granite-sheathed sides represent both the six points of the Star of David and the six million Jews murdered during the Holocaust. Inside, the Museum’s 30,000 square feet are devoted to three themes on three floors: “Jewish Life a Century Ago,” “The War Against the Jews,” and “Jewish Renewal.” The exhibitions include more than 2,000 photographs, 800 cultural and historical artifacts, and twenty- four original documentary films.

The park’s handsome open space — product of an unusually fertile collaboration of three design firms — combines a grassy terrace, mysteriously suggestive viewing pavilions, and angled asymmetrical garden beds. The pavilions, with thick walls and giant arches reminiscent of ancient Roman ruins, offer a paean to brick, set in perhaps a dozen different patterns. The terrace and the pavilions are oriented to the stunning view of the Statue of Liberty, one of the most dramatic vistas anywhere in the city.