The Skyscraper Museum is devoted to the study of high-rise building, past, present, and future. The Museum explores tall buildings as objects of design, products of technology, sites of construction, investments in real estate, and places of work and residence. This site will look better in a browser that supports web standards, but it is accessible to any browser or Internet device.

TIMES SQUARE IS NAMED AFTER A SKYSCRAPER

Times Square, 1908. Library of Congress.

In 1904, the New York Times moved from Park Row in lower Manhattan to an area of theaters, hotels, and other entertainments, then known as Longacre Square. Publisher Adolph Ochs selected an exceptionally conspicuous site for his tall and slender tower - a small triangular lot created by the diagonal crossing of Broadway and Seventh Avenue on the block between W. 42nd and 43rd Streets. The tiny footprint of the tower, only 4,000 square feet, was extended under the sidewalk by a large vault where the presses were located and where a direct connection to the new IRT subway platform speeded the distribution of papers.

The slender, wedge-shaped Times Tower faced north and established both the vertical and visual axis of an expansive open space. The great "urban room" created by the crossing of major streets and walled by the bordering buildings was unusual in Manhattan's grid. This intensely urban space was not edged by greenery, as at 23rd Street and Madison Park, or laced through with an elevated rail line, as at Herald Square, but was illuminated and animated by the bright lights of Broadway.

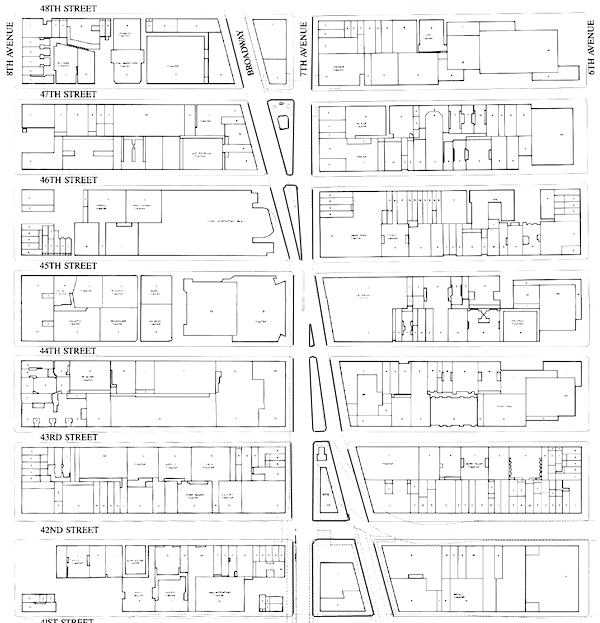

The "bow tie" of open space created by the irregular blocks between 42nd to 47th Streets define Times Square officially on a map, but the perceptual boundaries encompass a much larger district.

Plan of Times Square included in the original Times Tower Site Competition Packet, 1984. On loan from Lance Jay Brown.

NEWS, CROWDS, & NEW YEAR'S EVE

Times Square, D-Day, 1944. Library of Congress.

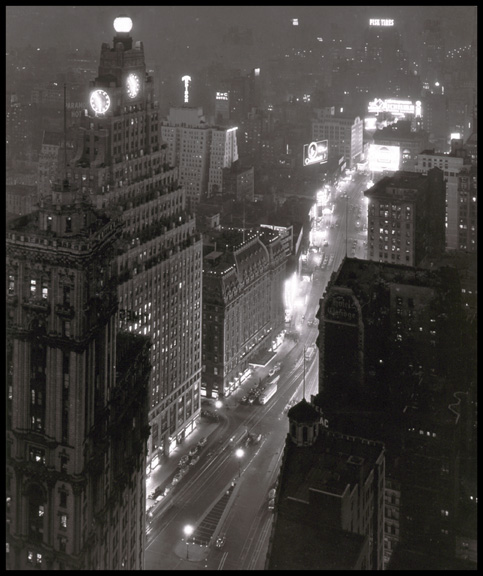

Times Square aerial view, 1932.

Library of Congress.

Crowds have congregated in Times Square for news and collective celebrations since 1904, when a fireworks display inaugurated the Times Tower. The tradition of the lighted ball drop on New Year's eve cheered in Times Square and now watched on TV by millions began in 1907.

The famous electronic "zipper" on the Times Tower, which flashed news headlines in real time from 1928 until 1963, became a fixture of New York life. Formally named the Motograph News Bulletin, the zipper consisted of 14,800 light bulbs in a band 380 ft. long and 5 ft. tall. An operator typed each message and animated the scroll that encircled the wedge-shaped building three stories above the street.

Many iconic photographs of Times Square document the crowds that formed to read the headlines and celebrate events such as the victories of World War II, including the D-Day invasion of June 7, 1944, shown in the photograph above.

The night view of the bow-tie area of Times Square in 1932 shows the northern stretch of the "Great White Way" of Broadway brightly illuminated by the marquees of theaters and large electronic billboard signs called spectaculars. The 1927 Paramount Building with its illuminated clock is notable as the only true skyscraper added to the area in the years between the Times Tower and One Astor Plaza, which would rise one block to its north in 1972.

TIMES TOWER | ONE TIMES SQUARE

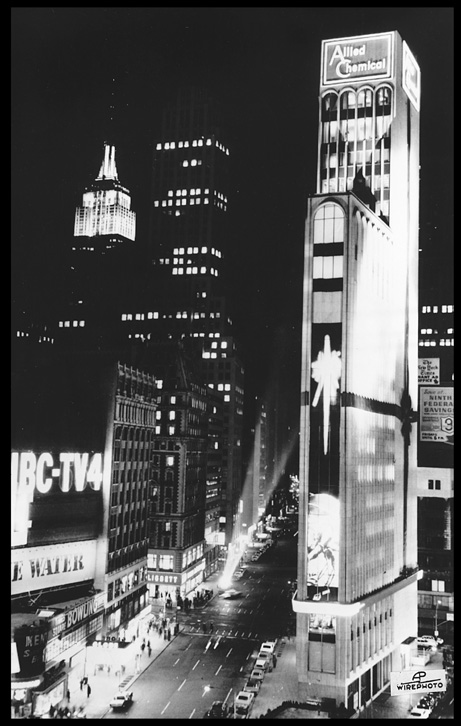

Times Tower facade recladding models, 1963 HLW International.

Allied Chemical Building Collection, 1965 HLW International.

Few people today realize that the

building at the heart of Times Square covered with gigantic LED signs and screens - and the tower from which the New Year's Eve ball drops - is the same structure that architects Cyrus Eidlitz and Andrew McKenzie designed and constructed in 1904. The ornate terra cotta facade was completely stripped off for a modernization in 1963 by the new owner of the tower, Allied Chemical, who hired the Eidlitz-successor firm Smith, Smith, Haines, Lundberg & Waehler (now HLW International) to update the building. They stripped bare the steel frame and replaced the walls, windows, and identity of the tower with smooth white marble panels. Since the 1990s, the building has served primarily as a superstructure for lucrative signage. The series of three models, shown above, illustrates the stages of the re-cladding process

1905 New York Times moves into new headquarters designed by architects Eidlitz and McKenzie.

1907 New Year's Eve: First ball drops from the tower, starting new tradition.

1913 New York Times outgrows its tower and moves to 229 W. 43 Street.

1928 Nov. 6: the "Zipper," an illuminated bulletin board of news headlines, is placed on Times Tower.

1961 Lighting and sign designer and entrepreneur Douglas Leigh buys the Times Tower, which becomes known as One Times Square, with a plan to turn the building into "a showcase for signs."

1963 Leigh sells the tower to Allied Chemical Corporation which hires architects Haines, Lundberg, Wahler to replace the terra cotta fa�ade with a new exterior of white marble and grey glass. Allied Chemical creates exhibits featuring displays of science, technology, and their products.

1975 Developer Alex Parker buys the Allied Chemical Tower and plans to add four floors and clad it in glass in a design by Gwathmey Siegel.

1981 Parker sells One Times Square to Swiss investors.

1983 October: Times Square Plaza, the design of four matching office towers by Philip Johnson and John Burgee for Park Tower Realty, is unveiled.

1984 March: Municipal Art Society competition for Times Tower site.

URBAN RENEWAL AND URBAN DESIGN

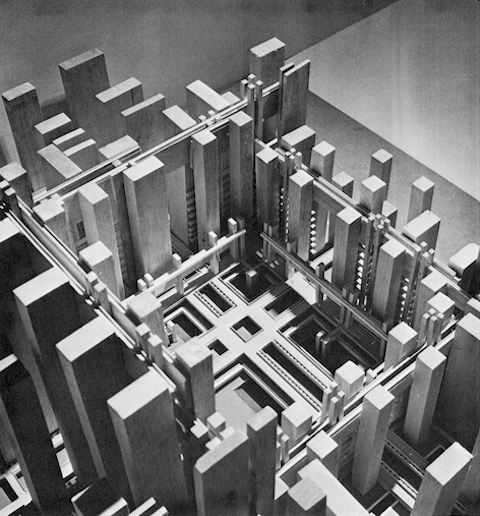

LEFT: "West 42nd Street Office Cluster", Regional Planning Association, 1969. RIGHT: Model of the Portman Hotel. Courtesey of John Portman & Associates

The 1960s and '70s were decades of both urban crisis and planning optimism that rationalist design on a large scale could solve urban problems or defend order against assault.

In this model of a dense new office district on the axis of W. 42nd St. near Times Square, envisioned by the Regional Plan Association in 1969, the emphasis was placed on increased bulk and efficient horizontal and vertical transit and linkages. A grid of closely spaced high-rises would connect the suburban commuter world of Grand Central Terminal to the subway transit hub of Times Square. Multi-level pedestrian flows were more of a priority than the life of the street and sidewalks.

In 1973, with the support of the City, architect John Portman successfully competed to become both the designer and developer of the massive hotel, seen in the images at the right, on the full block of Broadway between 45th and 46th Streets. Like contemporary Portman projects in Atlanta, Los Angeles, and Detroit, his modernist design was both monumental and inwardly oriented around a full-height atrium space. The project was announced with fanfare by Mayor Lindsay in 1973, but various obstacles, including the City's fiscal crisis, stalled progress for a decade. The hotel was completed in 1985 as the Marriott Marquis.

WEST 42ND STREET AND THEATERS

Cover Image from the 42nd Street Development Project Design Guidelines.

Cooper, Robertson & Partners

The broad definition of the Times Square district includes the blocks of W. 42nd St. between Seventh and Eighth Avenues. The concentration of theaters that lined these cross-town blocks from the early 20th century was the economic and social lifeblood of the area. By the 1970s, though, the theaters and movie palaces had moved dramatically downscale, featuring action films, porn, and peep shows. Crime was rampant and intractable: conditions seemed to defeat all attempts at urban renewal.

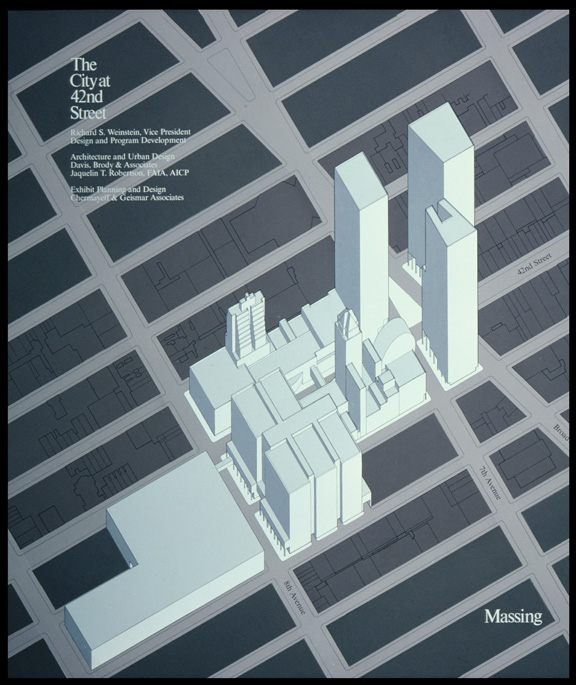

City at 42nd Street Massing Axonometric, 1978. Cooper, Robertson & Partners.

In 1979, the 42nd St. Redevelopment Corp. launched a new plan called "The City at 42nd Street" directed at the blocks between Seventh and Eighth Avenues and an additional block from 40th to 41st St. envisioned as a mammoth Fashion Mart. An impressive list of consultants worked on a detailed proposal funded by a $500,000 grant from the Ford Foundation and corporate support. The stated goal of this private initiative was "to change the character of the 42nd Street/Times Square Area, using a combination of restoration, demolition, and new construction." Returning theaters to 42nd St. was a particular focus, but other popular entertainments were proposed. Indeed, the plan seemed so like a theme park that Mayor Koch vetoed it as "Disneyfication."

One aspect of The City at 42nd Street plan was particularly important for the area's future development and survived in all subsequent plans: the cluster of high-density skyscrapers intended for the corner sites at the intersection of Broadway and Seventh Avenue. These were linked to a funding strategy that would support the acquisition of the historic theaters and subway improvements.

THEATERS AND SKYSCRAPERS

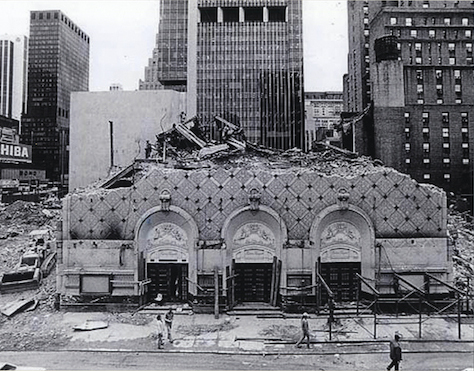

Demolition of the Helen Hayes Theater, 1982. Courtesy of Lee Harris Pomeroy.

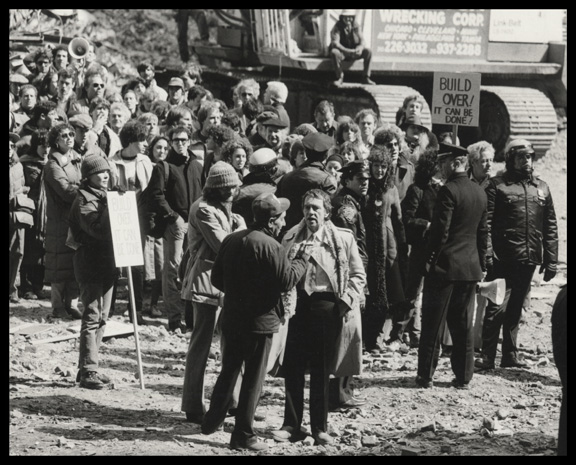

Helen Hayes Theater demolition protest, Joe Papp in center, 1982. Courtesy of Lee Harris Pomeroy.

In the 1980s, there were two distinct districts of theaters in what is and was referred to as Times Square. One, mostly north of 42nd St., was "Broadway" - both the physical place and the economy of the legitimate theaters. The other was the downscale or derelict historic theaters on W. 42nd St. such as the New Amsterdam and Victory (restored as the New Victory). In both venues, many stakeholders asserted conflicting interests and objectives.

For the industry of Broadway and large theater owners and producers such as the Shubert and Nederlander organizations, their physical properties were both businesses and real estate assets. Early twentieth-century theaters were mostly low-rise structures occupying land that had the potential to be developed for a "highest and best use" - to apply the parlance of real estate. This use would be skyscrapers; indeed, with recent zoning law incentives constructing new theaters within towers was encouraged.

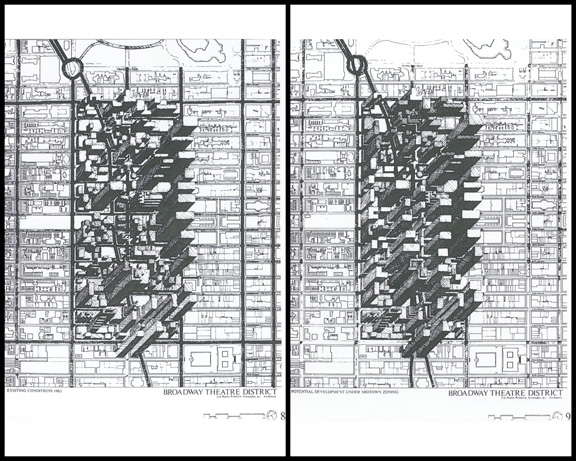

Courtesy of Lee Harris Pomeroy

Many feared that skyscrapers would overwhelm the district with their height and bulk and corporate office buildings and tenants would change its essential character. The drawings (above) by Lee Harris Pomeroy, an architect who led a study by the group "Save the Theatres, Inc.," pictured the contrast between the existing conditions of high-rise development in the theater district with a potential full build out under the Special District Zoning Resolution approved in 1982.

For actors and other theater artists, the survival of Broadway meant jobs, but many also became active in the preservationists' cause to save the historic buildings, which at that time had no landmark protection. The demolition of the Morosco and Helen Hayes theaters in 1982 ignited protests, including the one documented in the photograph of Joseph Papp being interviewed on the site. In 1988, twenty-eight of the district's historic theaters were approved for landmark designation.

POSTMODERN SKYSCRAPERS

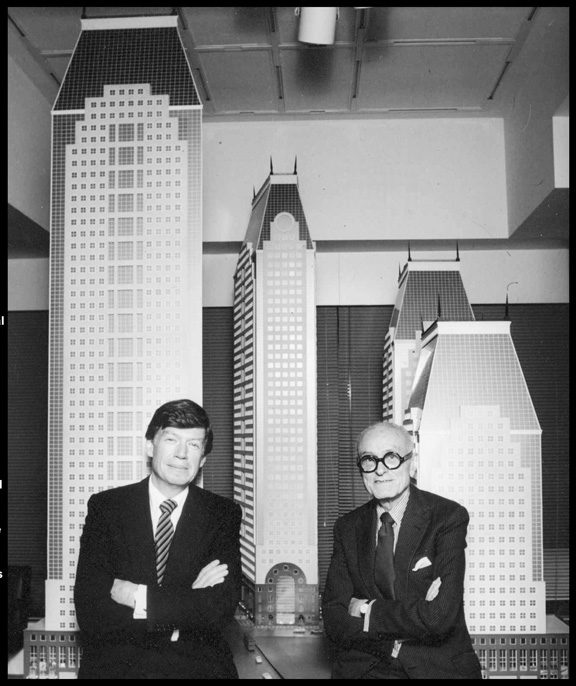

LEFT: John Burgee and Philip Johnson with their model of the proposed 42DP office towers, 1984. Photo: Bernard Godfryd. Courtesy of Lynne Sagalyn.

RIGHT: Times Square Center 1984 Rendering with Skeletal Times Tower, Johnson/Burgee Architects, Courtesy of Alan Ritchie. Rendering by Patrick Lopez.

In 1983, the developer George Klein and his company Park Tower Realty were awarded the development rights for all four skyscraper sites at the corners of Broadway and Seventh Avenue at 42nd Street. The Government - in the guise of the 42nd St. Development Project (42DP) - established the size and sites of the towers, a total of 4.1 million sq. ft. of commercial space.

Klein chose as his architect for all four towers Philip Johnson, who was then in his late seventies and had reigned for a decade as the doyen of American architecture. A few years earlier, Johnson had essentially invented the "Postmodern skyscraper" with his design for the headquarters for AT&T, which featured a masonry curtain wall and sported an ornamental "Chippendale top."

Johnson, seen here in front of an enormous model of their project with his partner John Burgee, treated the commission as an opportunity to reshape Times Square by creating an ensemble of buildings with matching granite bases, a checkerboard of punch windows, and glass mansard roofs. Like Rockefeller Center, "Times Square Center" was intended to create a sense of place through its monumentality and harmony of materials.

Critics of the project from many quarters spoke out against the very premises of the Johnson and Burgee first scheme, which included the demolition and elimination of the original Times Tower. Many variations of the design ensued.

ANOTHER POSTMODERNISM

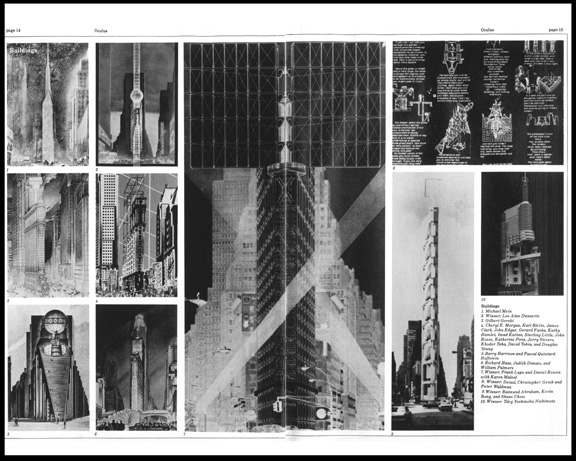

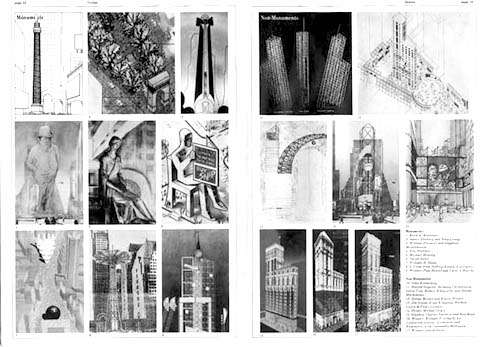

Oculus Magazine, vol. 46, no. 3, 1984.

Oculus Magazine, vol. 46, no. 3, 1984.

Just as the over-scaled, collage classicism of Johnson and Burgee's Times Square Center represented one aspect of 1980s Postmodernism, the Times Tower Site Competition with its 565 entries reflected a different set of "pomo" ideas: multiplicity, irony, and fascination with semiotics and buildings as signs.

The competition grew directly out of the widespread negative reaction to the monumentality of the Johnson and Burgee design, which also proposed to demolish the remains of the original Times Tower to serve as a forecourt for their ensemble. The Municipal Art Society, in partnership with the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA), organized an "ideas competition" for alternative proposals for the triangular site. The submissions were local, national, and international and spoke to the notoriety of the controversy over the future of Times Square.

Oculus Magazine, vol. 46, no. 3, 1984.

Oculus Magazine, vol. 46, no. 3, 1984.

The records of those names have, unfortunately, been lost, and the great majority of original boards were not returned after the jury and exhibition of the winners. News accounts of the events have made it possible for The Skyscraper Museum to contact the artists and assemble many of the original boards or make facsimiles. One of the fullest accounts of the competition and its winners was published in the November 1984 Oculus, a newsletter of the AIA New York Chapter, pages of which are reproduced here. The proposals represented a cacophony of architectural directions, from poetic musings, to irreverent one-liners, to theory-driven manifestos.

TTIMES SQUARE CENTER, 1984 and 1989.

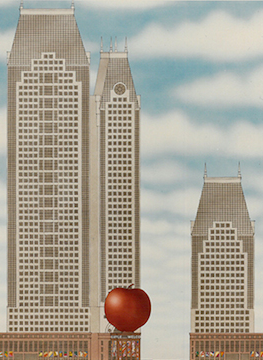

LEFT: "The Big Apple" in Times Square, South Elevation. Courtesy of Frederic Schwartz.

RIGHT:

Times Square Center 1989 Redesign, John Burgee Architects with Philip Johnson, Courtesy of Alan Ritchie.