The Skyscraper Museum is devoted to the study of high-rise building, past, present, and future. The Museum explores tall buildings as objects of design, products of technology, sites of construction, investments in real estate, and places of work and residence. This site will look better in a browser that supports web standards, but it is accessible to any browser or Internet device.

ZONING, SKYSCRAPERS, AND THEATERS

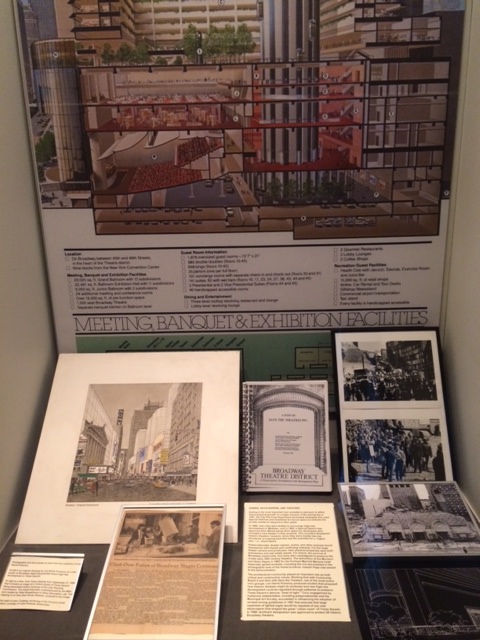

Zoning is the most important tool available to planners to affect future physical growth. In a major revision of the zoning law in 1961, the City Planning Department developed strategies that used Special Districts and incentives for bonus space to motivate the private market to respond to their goals.

In 1980, new rules were drafted to encourage high-rise development in Midtown, and in 1982, a Special District was approved that offered bonus floor space for developers who included new theaters in their projects. This incentive threatened historic theaters, however, since they were mostly low-rise structures occupying land that had the potential for a "higher use," i.e., skyscrapers.

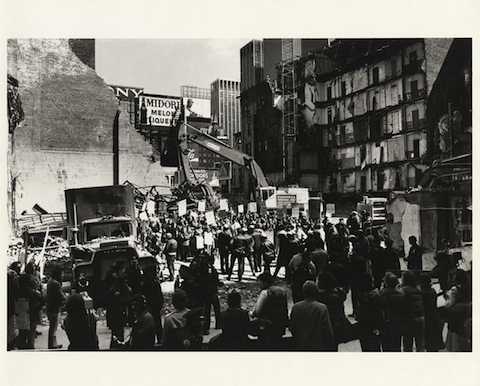

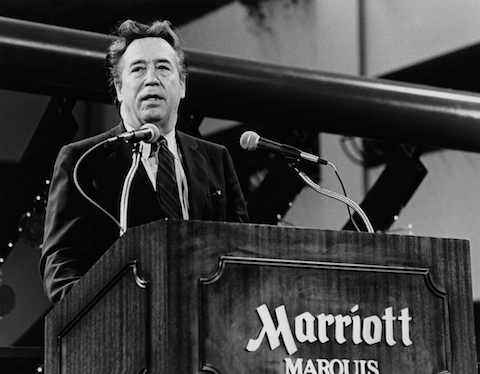

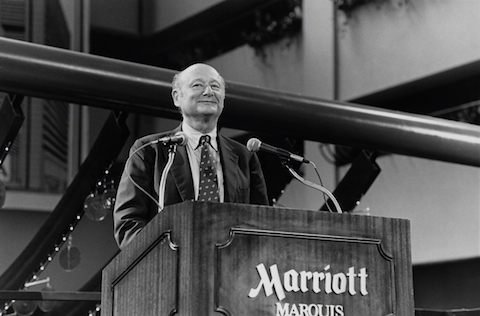

Preservationists, theater owners, actors, and other activists found themselves with shared and conflicting interests. For the large theater owners and producers, their physical properties were both businesses and real estate assets. For actors, the survival of Broadway meant jobs, but many also campaigned to preserve the ornate early 20th century theaters. The demolition of the Morosco and Helen Hayes in 1982 for the Portman Marriott Marquis hotel especially ignited protests, including the one documented in the photographs here of the famed producer Joseph Papp interviewed at the demonstration.

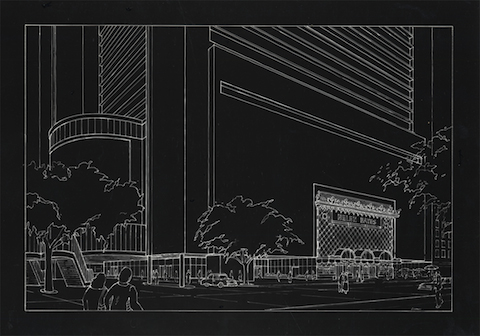

Top left: Pomeroy Broadway Study Rendering, circa 1982. Lee Harris Pomeroy.

Bottom left: Broadway Theater Demolition Protest, Circa 1982. Lee Harris Pomeroy.

The architectural community played an important role as both critical and constructive voices. Working first with Community Board 5 and then with Save the Theaters, one of the most active civic groups, Lee Harris Pomeroy produced studies that proposed how historic theaters might be protected and new high-rise development could be regulated through setbacks to preserve Times Square's famous "bowl of light." Civic engagement by numerous stakeholders, including preservationists and the Municipal Art Society, succeeded in influencing the adoption of revised zoning guidelines in 1987 that ensured that large expanses of lighted signs would be required of any new skyscrapers that shaped the great "urban room" of Times Square. In 1988, landmark designation was approved to protect 28 historic Broadway theaters.�

Mayor Koch and John Portman speaking at the opening in 1985.

Credit, John Portman Associates.