The Skyscraper Museum is devoted to the study of high-rise building, past, present, and future. The Museum explores tall buildings as objects of design, products of technology, sites of construction, investments in real estate, and places of work and residence. This site will look better in a browser that supports web standards, but it is accessible to any browser or Internet device.

NEW YORK CITY IN THE 1880s

Tribune Building; Western Union Building; Evening Post Building; Elevators; Central Park Apartments; The Chelsea; Tower Building; The World Building; American Surety Building; Gillender Building; Park Row Building; Netherland and Savoy; Waldorf Astoria; Mills House 1 & 2; Lofts; Asch Buidling.

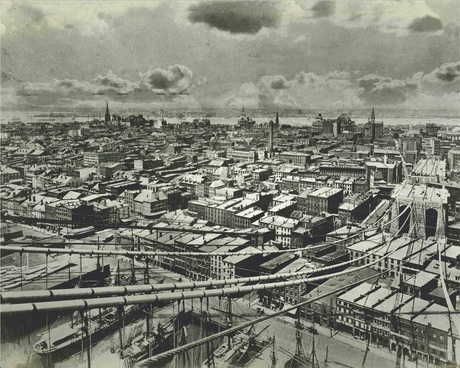

Downtown Manhattan showing Brooklyn Bridge, 1881, photo by Fred Palumbo, World Telegram & Sun, Library of Congress.

The elevated view of lower Manhattan in 1881, photographed from the strung cables, without roadbed, of the unfinished East River (Brooklyn) Bridge captures New York as a still largely low-rise city, but also at the point of a changing identity. In the foreground, visible in extraordinary detail, are the dense blocks of four- and five-story “walk-ups” of attached brick and stone structures that served as businesses, warehouses, and manufacturing, mostly connected to the shipping wharves on the East River.

In the distance, though, rising high above the homogenous horizontal blocks and taking shape along the commercial spine of Broadway is the new business skyline, with its ten-story, elevator office buildings, the Tribune Building, Western Union, and Evening Post.

The vertical accents of the previous decades – the spires of Trinity Church and St. Paul’s, and the chimney-like shot tower – pale in comparison to the girth and business towers that anchor an emerging skyline.

TRIBUNE BUILDING

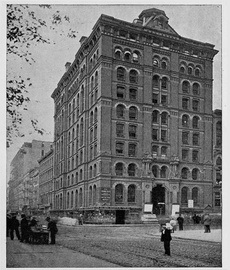

Library of Congress, HABS digital.

Completed in 1875, the Tribune Building, home of the venerable New-York Tribune, was one of three contemporary tall office buildings – the others were the Equitable and Western Union buildings, nearby on Broadway – that historians have called “proto-skyscrapers.” In the early 1870s, these three were also the first office buildings in the city to use elevators, even though passenger lifts had been introduced into hotels and dry goods stores in the late 1850s. The Tribune’s two elevators were powered by steam and illuminated by gaslight chandeliers.

At eleven stories, the Tribune was the first tall building on Newspaper Row across from City Hall. It soared above its neighbor and competitor, The Sun, and became the tallest office building in the city by virtue of its clock tower, which reached 260 feet.

The extravagant architectural statement was the project of Whitelaw Reid, who had become editor-in-chief in 1872. Established by Horace Greeley in 1841, the New-York Tribune was the country’s most respected and influential political paper and had the largest circulation in the nation for its weekly edition. Reid aspired to erect a “printing palace” that would be the most technologically advanced newspaper operation of the time and would be entirely fireproof, a key consideration after the major fires in Chicago and Boston. The Tribune occupied the eighth and ninth floors: the remaining floors were rented to tenants.

Reid worked closely with the prominent architect Richard Morris Hunt and acted as contractor. Typical of the 1870s, the structure was load-bearing masonry. As the Scientific American wrote on May 1, 1875:

The structure is of great height and immense solidity, and is built of brick laid in cement, with dressings of stone and granite. The finial on the clock tower is 260 feet above the sidewalk, surmounting a building containing sub-cellar, basement, nine stories, and attic. The walls of the lower portion, sustaining the great weight of the masonry, are 5 feet, 2 inches to 6 feet thick. The building is claimed to be absolutely fireproof. No wood is used in its construction, except for floorings, doors, and windows.

WESTERN UNION BUILDING

Western Union Building, dcmny.org, New York-Historical Society.

At 230 feet tall, the Western Union Building, completed in 1875, became the city’s second-tallest office building after the Tribune, and its spired silhouette dominated the vista of Broadway. It was the first “skyscraper” – although that term was not used in print until the 1880s – of George B. Post, who in the following decades would become one of New York’s most prolific architects of tall buildings, designing twelve of the structures featured in our survey, including Joseph Pulitzer’s World Building, which in 1890, at 309 ft., took the title of the tallest office building in the city and in the world.

Like its contemporaries, the Tribune Building and the Evening Post Building, Western Union was a masonry bearing-wall structure that also employed some cast-iron columns and wrought iron girders and beams. Architecturally, it was a horizontally striped Victorian pile of red brick and gray stone, crowned with a high mansard roof built over a metal frame. The ornate roof capped an arcaded eighth story where the company’s telegraph operators sent and received messages from a net of wires that criss-crossed rooftops.

From the mid-19th century, telegraphs were the major method of long-distance communication. Using code developed by Samuel Morse to covey “written messages by electricity,” competing companies connected cities, the continent, and opposite sides of oceans with wires and cables that, for considerable charges, carried vital messages. By the 1870s, through inventions and business mergers, Western Union had become the dominant telegraph company. As an article on the new building in the journal The Aldine described:

“No single enterprise, in the whole world, has grown so rapidly within a few years, as the telegraph interest of America, of which the Western Union Telegraph Company is the principal exponent; and perhaps it is quite correct that the Company should be the builder and owner of one of the most remarkable structures on the continent, if not in the world…. That the Telegraph Building is to be, architecturally and practically, an immense success, there can be no question; its great height making the amount of disposable space within, simply enormous; and its location, so near the Post Office and the great business centres, rendering its availability quite as marked as its size”.…

Called by The Daily Graphic the city’s new “business palaces,” the Western Union Building, like the Tribune, advertised the success of their companies, but they also offered offices for rent on their middle floors.

EVENING POST BUILDING

Evening Post Building,

King’s Photographic Views of New York, 1895.

Collection of the Skyscraper Museum.

The third of the trio of “first skyscrapers” of 1875 was the Evening Post Building, the new headquarters of the respected newspaper the New York Evening Post, which had been established in 1801 by Alexander Hamilton in 1801 as a Federalist broadsheet and whose abolitionist editor-in-chief William Cullen Bryant had led since 1828.

Like the Tribune Building and Western Union, just across Broadway, the Evening Post was a load-bearing structure of brick, with some stone trim. Vaguely Romanesque in style, with thick walls and corner piers and deep-set windows, the design by the little-known architect Thomas Stent was far more restrained than its ten-story contemporaries, and without a clock tower or ornate roof, it reached a height of only 140 feet. Indeed, the Post wrote of its new building in its issue of July 1, 1875 supplement that its simplicity would be “admired more for its massiveness and substantiality, and for its complete adaptation to the uses for which it was constructed, than for anything peculiar or striking in its outlines or extravagant in the treatment of its interior.”

The main Broadway entrance, raised a half-story above street level, as was common at the time, led to the major commercial spaces and the lobby access to the hydraulic elevators. The upper floors were partitioned offices, all leased to tenants except for the top floor, which was reserved for the paper’s editorial offices and space for the compositors. As at the Tribune Building, the printing presses and other machinery operated in the basement levels, and compositors of the job-printing department worked in the vault spaces below the sidewalks on Broadway and Fulton Street.

ELEVATORS

Scientific American,

April 16, 1881. Collection of The Skyscraper Museum.

Elevators made skyscrapers possible. They created a new condition whereby the stories above the fourth or fifth of a building – the limits of human stamina, or patience to walk up – could have the same, or greater value in rent than the floors below. Indeed, as the Scientific American of April 16, 1881 noted: “as a consequence of the introduction of improved elevators…quick and convenient access is afforded to the several floors of a building, without calling for the loss of time and severe labor required to mount long flights of stairs.”

Although the first passenger lifts had been introduced into hotels and dry goods stores, such as the Haughwout Building at Broadway and Broome, in the late 1850s, the first use in an office building came only in 1870 in the new Equitable Building at 120 Broadway. This time lag of nearly twenty years from the first public demonstration by Elisha Graves Otis of his invention of the “safety brake” at the Crystal Palace exhibition in New York of 1853, to the adoption of the revolutionary technology into office buildings is surprising and makes clear that there were other factors at work in determining the number of stories and heights of high-rises. A combination of the Civil War and the Panic of 1873, a financial crisis that lasted through the end of the decade, must have had an impact on new construction, but the relative absence of tall office building construction through the later 1870s is notable.

Nevertheless, by 1881, as the Scientific American noted, the demand for space was being answered by vertical expansion:

“The most eligible building sites in our large cities now command almost fabulous prices. The figures paid for a small lot on which to erect a warehouse in some parts of this city are equal to a very respectable fortune. On this account owners are generally putting up taller buildings, or changing those already erected, so as to give additional stories above the roofs of old-time structures. Thus, in New York city and some of the other large business centers of the country, the available space for offices, etc., is being doubled in a manner which would have been deemed entirely useless twenty years ago”…

CENTRAL PARK APARTMENTS

Central Park Apartments, 59th Street, West. Wittemann, Adolph, Select New York, 1889.

The Central Park Apartments, otherwise known as the Spanish or Navarro Flats for its developer Jose F. De Navarro, was praised as “the most vast, complete, and permanent apartment houses ever as yet erected in any country.” Stretching 425 feet along the southern edge of Central Park on 59th Street, east of Seventh Avenue, the massive 10-story complex “in the “Moorish style” was composed of eight smaller separate buildings, each named after a Spanish city. Navarro financed his project creatively, according to American Architect and Building News, intending “to erect the buildings in his own name, and sell the apartments absolutely to those who wished to occupy them by means of trust-deeds and perpetual leases.” The buildings could be constructed one by one, and the sale of the finished apartments paid for the construction of the next. The first four buildings—the Madrid, Lisbon, Barcelona, and Cordova—were built in 1883, and the Valencia, Granada, Salamanca, and Tolosa were completed in 1885.

The complex was designed by French-born architect Philip Hubert and his firm, Hubert Pirsson & Co., who were credited with originating the cooperative apartment system as well as the duplex-apartment layout in New York. The cooperative apartment system, commenced in 1880, allowed residents to partially and collectively invest in ownership of the building.

Each building contained twelve apartments, some of which included up to three floors and up to six bedrooms, a parlor, living room, dining room, and library. Apartments sold for $15,000 to $20,000 with annual maintenance fees from $1,000 to $2,000. The complex was arranged around a system of courtyards that gave light, air, and access to the buildings and the interior of the block.

THE CHELSEA

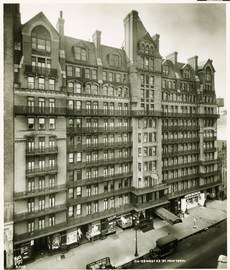

Chelsea Hotel, New York Public Library, Digital Collection.

The Chelsea Hotel, with a cliff of solid red-brick paired with lacy High Victorian cast-iron balconies, was designed by Philip Hubert and his architecture firm, Hubert Pirsson & Company Construction started in 1883. The building opened in 1885, not as The Chelsea Hotel, but as The Chelsea Apartments. Like other residences of the Hubert Home Club, The Chelsea was originally intended to be a cooperative-apartment sold to multiple owners. The cooperative-apartment model appealed to those concerned with both price and prestige as a more permanent home rather than temporary accommodations. Following the success of earlier Hubert Homes ventures, The Chelsea received generous financial backing from capitalists, allowing for its extravagant interior fittings. The rooms sold out immediately upon opening with suites at premium over the original cost.

The Chelsea contained 97 suites, each ranging from 3 to 12 rooms, furnished with woodwork of the owner’s choice. In addition to its elevator, the lobby boasted a spiraling staircase with cast-iron railings and mahogany handrails. Residents also received a continuous income from the building’s storefront and tenants on the upper two stories. The attic story in the pavilions originally served as a studio apartment for artists, since its opening. At 180 feet tall, the Chelsea stood twice as tall as what the residential height limit of 1885 allowed, remaining the tallest building in New York until 1899.

THE TOWER BUILDING

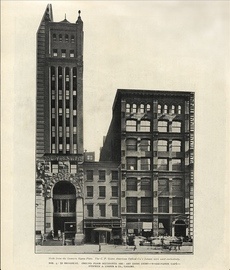

Tower Building, c. 1909, Both sides of Broadway (1909)

Collection of the Skyscraper Museum

Slenderness in commercial architecture depends on engineering technology. Masonry construction is more suited to pyramids, and medieval cathedrals demonstrated the limits of stone 700 years earlier. In the late 19th century, to create a tall urban building on a small or narrow, high priced lot, it was necessary to employ the new technology of steel-cage construction. As Chicago engineers and architects had demonstrated in their city since 1884, steel skeletons created more open (rentable) area on every floor and allowed fot larger expanses of windows.

The first tall building in New York to use metal-cage construction was the Tower Building at 50 Broadway (demolished 1914), designed by architect Bradford Lee Gilbert and completed in 1889. At 11 stories, it was not the tallest in the city, but with a frontage on Broadway of a mere 21.5 feet, it was extremely slender for its height. The novelty of its metal-cage construction was the subject of considerable attention in the popular press, as pundits predicted its collapse.

The NYC Building Code did not explicitly allow for skeleton-frame construction until 1892, but the Department of Buildings approved Gilbert’s individual application. As author and engineer Donald Friedman explains, the Tower Building had a hybrid structural system: “the side walls were bearing at the top four levels of steel framing, but were carried below that point on a frame consisting of wrought-iron beams and cast-iron columns. In other words, the Tower Building was, structurally, a four-story bearing-wall building sitting on top of a seven-story skeleton frame. The overall building was noticeably slender and the weight of the bearing-wall structure at the top probably helped the frame below perform: cast-iron columns cannot handle tension well, and the weight of the upper-floor masonry served as a pre-stressing compression load in the columns below.”

THE WORLD BUILDING

Newspaper Row, New York City, Detroit Publishing Co., c. 1905, Library of Congress.

Completed in December 1890 as the newspaper’s headquarters, the World Building—officially called the Pulitzer Building—expressed the ambitions and business genius of its publisher Joseph Pulitzer. At a height of 309 feet to the top of the dome, the paper’s new home on Park Row became the highest building in the city and the tallest office building in the world. (The Eiffel Tower still held the title as world’s tallest structure). Designed by architect George B. Post, the building comprised 18 stories — with 12 floors of rentable office space and four levels for the newspaper’s editorial offices in the drum and dome.

No expense was spared on the elaborate façade of red sandstone and terra cotta, Renaissance ornament, and figurative sculpture, which gave the appearance of an Old World masonry structure, while hiding the advanced metal-cage construction that Post encased within the walls.

The distinctive dome provided a visual identity for the newspaper. The image of the gilded top was used in advertising, graced covers of The World Almanac, and created a landmark on the skyline. At night, the top was illuminated with electric lights and the lantern at the top of the observation platform acted as a beacon for ships at sea.

In a booklet printed for the tower’s debut, the paper effused:

From Jersey’s shores, from Brooklyn Heights, from the beach of Staten Island, from points far remote, it is first discerned as one approaches New York looming above the busy metropolis, above Trinity’s lofty spire, above the tall towers and high roofs of its neighbors-a giant among the giants.

AMERICAN SURETY BUILDING

Collection of The Skyscraper Museum.

Designed by the prominent architect Bruce Price for the American Surety Company, a bond insurance business, the American Surety Building was a much praised and influential model for the skyscraper as an aesthetic object. Soaring 312 feet above Broadway at the corner of Pine Street, just opposite Trinity Church cemetery, which ensured great light and views, the ornate granite-clad tower became the second tallest building in the city when it was completed in 1895.

The American Surety Building was also an early and significant New York City example of early skeleton framing, curtain-wall construction, and caisson foundations, which carry the weight of the tower above down to bedrock. While the first high-rise in New York with a complete steel frame supporting an exterior masonry curtain wall was the narrow London and Lancashire Building erected in 1890, that now-demolished structure was only ten stories high and just 25 feet wide and stood on a narrow lot at 25 Pine Street. Although it was the earliest use of the new structural form in New York, it did not represent well the technology as it developed in the 1890s. The 23-story American Surety Building is a more substantial example of early skeleton framing, and it still stands prominently at 100 Broadway. A model of the steel skeleton and innovative caisson construction are displayed in the exhibition.

Price conceived of his skyscraper as a campanile, in the spirit of the tower of San Marco in Venice. Classical in its references, the form and façade was organized as a column, with a base, shaft, and capital, or, as Price noted, as pilaster, with “the seven flutes being replaced by seven rows of windows.” What made American Surety nearly unique among commercial buildings was that all four sides were finished with the same extravagant ornament. Quoting Price in an essay in the Architectural Record in 1895, the critic Russell Sturgis explained the architect’s view:

“The fact is the tower concept is the only artistic solution of the problem of high design. The great defect of most high buildings is the hideous back wall and the utter lack of care by the architect or the owner to make the interior sides, as they rise up beyond the surrounding roofs, architectural entities of any sort whatever. Our commercial buildings are almost without exception designed wholly with reference to their relation to the street while as a matter of fact they have no such relation at all, their aerial aspect being of more value to the city as a whole than the distorted partial views as a rule are that all we can obtain from the street.”

The original seven-bay tower of American Surety was widened by four bays in 1920.

THE GILLENDER BUILDING

Collection of The Skyscraper Museum.

When the Gillender Building was completed in 1897, it was the fourth tallest building in the city, measuring 306 feet to the tip of its spire. What was most remarkable about it, though, was its slenderness. On the tiny site of the six-story Union Building, on the northwest corner of Wall and Nassau streets, architects Berg and Clark packed twenty stories on a plot of only 26 x 73 feet. The tower employed a complete steel-skeleton frame that made its extreme slenderness possible.The engineers and steel erectors Post and McCord used built-up steel columns to carry the heavy gravity and wind loads, multiple spandrel beams to support the exterior walls, and wind bracing within the frame.

It was the extraordinary value of the land at the prominent corner of Wall, Broad, and Nassau streets – the heart of capitalism, flanked by the New York Stock Exchange, the headquarters of J.P. Morgan, the U.S. Sub-Treasury, and numerous banks – that made the enormous expense of the tiny, ornate Gillender Building both possible and profitable. The high demand for this prime location, combined with advances in steel-frame technology, drove developers and architects to capitalize on the escalating value of land in slender towers. In 1903, a chart of land values showed the price per square foot price for the intersection of Wall Street and Nassau Street to be the highest in the city at $400 psf. This number doubled by 1910 when the Gillender’s lot sold for $822 psf, another highest price ever recorded. Only twelve years after it was completed, the Gillender Building was demolished to make way for the 40-story Banker Trust Tower.

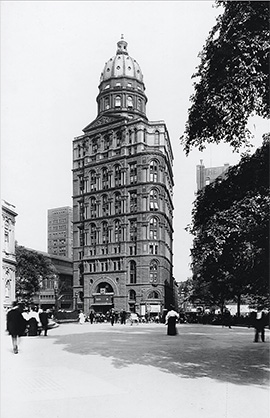

THE PARK ROW BUILDING

Park Row Building, 21 Park Row, Irving Underhill, c. 1912, Library of Congress.

The 30-story Park Row Building was the tallest office building in the world from its completion in 1899 until the Singer Tower in 1908. It rose 386 feet to its cornice and 391 feet to the top of the twin cupolas, with their domes and lanterns adorned with slender sculpted female figures.

Designed by architect R.H. Robertson and engineer Nathaniel Roberts, the building exploited the newly developed all steel-skeleton technology. The Park Row building’s main facade was a tall rectangle divided into horizontal sections marked by decorative string courses, balconies, and columns, and crowned with ornate twin cupolas in copper sheathing and sporting mythic maidens. The design was little loved by contemporary critics. One called the towers “insignificant terminations which add nothing,” and noted that in their close proximity, the Park Row and St. Paul buildings “stand and swear at each other” across Ann Street.

The Park Row Building, a designated New York City landmark since 1999, stands today facing the enlarged City Hall Park. The early skyscraper has been converted to residential units in its top twenty floors.

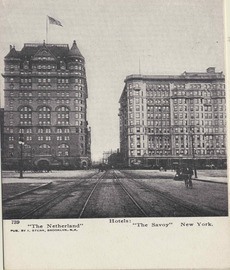

THE NETHERLAND AND SAVOY

Postcard of the New Netherland and Savoy Hotels Circa 1900. Collection of The Skyscraper Museum.

Hotels, like office buildings, are commercial architecture, designed and erected to earn revenue. Money could be earned through a variety of strategies, including renting large, luxurious rooms at high rates, at a “palace hotel” such as the Waldorf Astoria, or creating cubicles of clean, but tiny rooms to let at 20 cents a night, as at Mills House. Lodging could be rented by tourists for the night, or leased as residences by the week, month, or longer in “family hotels.”

Hotels were an important part of the social fabric of New York since colonial times, but in the 1880s, especially, they began to proliferate. A long article in the New York Times of October 19, 1890 summarized the boom in new construction, noting the profitability of the industry: “The hotel men of New-York are a contented lot just now. There never was a time when their business was so uniformly good as at present.”

The Times cited four reasons for the growing demand: “the constantly-increasing population of the largest city on the Western continent” and “the steady increase in the number of rich people (and) luxury-loving money spenders.” They also noted that many wealthy New Yorkers who were being compelled by expanding commercial development to relocate their mansions, in fact preferred “to go on living within hailing distance of the shops and the theatres…by taking rooms at a hotel.” Finally, the “tremendous increase in trans-Atlantic travel” was good for business: “Englishmen and Frenchmen are delighted with our best hotels. The comfort, the elegancies, and the conveniences excel anything that they can get at home, and they are willing to pay extravagantly for their entertainment.”

None of the lavish palace hotels of the 1880s reached ten stories. The first to do so was the Savoy, completed in 1892 (with additions in 1895). Together with the New Netherland, completed in 1893 it flanked 59th Street at the southeast corner of Central Park. At seventeen stories and 234 feet, the turreted New Netherland remained the tallest hotel in the city through 1900. Long-term residents there in 1894, according to the New York Times, numbered 225, including many families who had taken apartments for “the entire season…(and) had brought to the hotel pianos, paintings, and furniture.”

WALDORF ASTORIA

The Waldorf-Astoria, New York, 1900, Library of Congress.

The Waldorf Astoria Hotel was built in two phases, the first completed in 1894, and the second in 1897. Beginning as an 11-story structure on the corner of Fifth Avenue and 33rd Street, the hotel was expanded to occupy the full block to 34th Street, creating a monumental 16-story edifice that, with 1,300 rooms, was one of the largest and most luxurious hotels in the world.

The first Waldorf rose on the site of the Astor mansion, where Mrs. Caroline Astor famously entertained New York’s exclusive “Four Hundred” social set. The massive hotel offered 530 rooms: 350 of the 450 bedrooms had adjoining bathrooms. A suite of state apartments, reserved “for the proper reception of very great personages,” occupied the second floor, and an immense ballroom could be closed off for lavish private events. Like many high-class “palace hotels” of the period, the Waldorf housed both permanent and transient patrons, and, as the New York Times explained, was designed “to provide a series of magnificent homes for wealthy New Yorkers as an economical alternative to maintaining private mansions.”

The addition of the Astoria in 1897 cemented the hotel’s reputation as the “last word in luxury.” The opening of the hotel was celebrated with a charity ball attended by New York’s finest families, and the New York Times opined that “the entire Astoria building seems to be as complete and magnificent as modern workmen and modern art can make it.” Henry J. Hardenbergh, architect of other grand residential buildings such as the Dakota Apartments designed the Waldorf and the Astoria to seamlessly complement each other despite having different structural systems: mixed masonry bearing walls and steel skeleton, respectively.

Illustrating the cycle of Manhattan’s rising land values, the great hotel was demolished in 1929 and replaced by the Empire State Building.

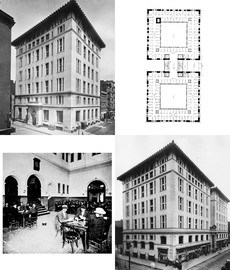

MILLS HOUSE 1 & 2

Clockwise from top left: Mills House No. 2,

Architectural Record

vol. 11 no. 3 April 1902 p. 46; Typical Floor Plan of Mills House No. 1, Architectural Record vol. 11 no. 3 April 1902 p. 43; Central Court of Mills House No. 2, Architectural Record vol. 11 no. 3 April 1902 p. 47; Mills House, DCMNY, New York Historical Society.

Developed by wealthy businessman D.O. Mills and designed by the philanthropically-minded architect Ernest Flagg, the two Mills House hotels established a model for providing low-cost lodging for single unmarried working-class men. The first Mills House on Bleecker Street opened on November 1st, 1897, the same day as the luxury Astoria Hotel, its polar opposite. The Mills House provided rooms for 20 to 30 cents per night with dinner for an additional 15 to 20 cents. The building was divided into 1,554 austerely furnished bedrooms, most measuring only a minimal 7.5 by 6 feet. Residents were expected to uphold such standards of cleanliness and strive for independence. The hotel provided communal dining rooms, shared bathrooms, a library, smoking and lounging rooms, and a large courtyard.

Such lodging houses helped deal with the sanitation problems that came with urbanization. Following the success of its predecessor, a smaller Mills House 2 (upper left) opened on the corner of Rivington and Christie Street, offering 600 bedrooms under the same premise of compact, utilitarian, and economical housing. As described in the Engineering Record of October 8,1898: “At both houses, the essential conveniences of the ordinary hotel can be obtained at the lowest possible prices; they are not however, intended as charitable institutions, although their success would seem to point toward a partial solution of the problem of housing the industrious, self-respecting man with little money, as it takes him from the cheap lodging house, where he was forced to mingle with objectionable characters”.

LOFTS

707-709 Broadway, 1896,

Both Sides of Broadway

by Rudolph M. Leeuw

Unlike other types of commercial buildings, such as offices or hotels, lofts were built without a program for use and particular design requirements. The facades could be plain or fancy, as the developer chose, but the lobbies were modest and the number of elevators minimal. Lofts were erected as speculative real estate to earn rents. They housed multiple tenants who rented all or part of one or more floors.

Lofts were a traditional form of New York commercial building used for warehousing or light manufacturing from the early 19th century, but like all structures through the 1870s, they rose only four or five stories. Taller loft buildings began to proliferate, especially replacing older mercantile structures along Broadway from Canal Street north to Madison Square, principally after 1895. Many contained businesses related to the garment industry, New York’s largest manufacturing sector. The multiple signs affixed to facades visible in old photographs capture some of the businesses: Eagle Skirt Co., Petticoats; Preiss Bros, Raincoat Specialists; The Binger Co., Advertisements and Signs; H. Gallert Belts; J. Marrow, Ostrich Feathers.

Some lofts were big boxes with large floor plates that were well suited to factory-style production such as shirtwaists sewn by rows of garment workers or floors of presses of printers and lithographers. Many buildings, though, were thin slivers of only 25 to 50 feet frontage erected by individual entrepreneurs who were making a first foothold in the real estate business. Some skinny structures poked above older low-rise blocks like a strange slice of a lost larger building. Others built separately, but on contiguous lots, combined to form a block-long behemoth, like the 12-story cliff of lofts on the east side of Broadway just south of Houston Street.

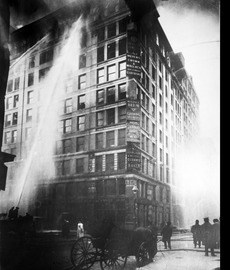

ASCH BUILDING

Triangle Waist Company Fire at the Asch Building, March 25, 1911. Kheel Center, Cornell University.

Completed in 1900, the Asch Building was typical of a cluster of loft and light manufacturing buildings erected in the blocks between Broadway and Washington Square, where New York University had a small campus. The loft became infamous on March 25, 1911, when the Triangle Waist Company’s factory, located on the three top floors of the “fireproof” 10-story building, caught fire, tragically killing 146 workers.

As the historian Andrew Dolkart explained the history of lofts in his 2012 exhibition for the Museum, “Urban Fabric: Building New York’s Garment District:”

“A ‘loft’ is an open and flexible space, unencumbered with partitions, intended for industrial, commercial, or warehousing uses. Lofts generally housed multiple tenants who rented all or part of one or more floors. As the garment manufacturers were forced out of tenement sweatshops beginning in the 1890s, they first moved their factories into old loft buildings. Soon scores of new lofts were erected to meet the demands of the expanding industry. The principal concentrations were located on and near Broadway near Washington Square and on blocks near Union Square.

The lofts erected in the 1890s and first years of the 20th century were generally metal-framed buildings of 8 to 10 stories with brick and stone facades. Stores occupied street-level spaces. They had passenger and freight elevators, large windows for light and ventilation, steam heat, and plumbing. Most significantly, the new lofts had electricity, which permitted the installation of efficient electric sewing machines, cutting machines, and other time and labor saving devices. They were also “fireproof” and were supposed to have adequate fire escapes and exits.

Fireproof was an insurance term that only meant a building would not be destroyed in a conflagration; it did not protect the safety of those working inside. Few buildings had sprinkler systems or non-flammable window frames… The building itself, as the term “fireproof” had promised, suffered little damage, and was repaired and reoccupied within a few months. The response of the press and the public, however, resulted in major reforms.”