The Skyscraper Museum is devoted to the study of high-rise building, past, present, and future. The Museum explores tall buildings as objects of design, products of technology, sites of construction, investments in real estate, and places of work and residence. This site will look better in a browser that supports web standards, but it is accessible to any browser or Internet device.

SINGAPORE SITUATED

The work of WOHA must be seen in the context of the region of Southeast Asia and their home city of Singapore. Only fifty years old from its independence in 1965, the tiny city-state of nearly 5.5 million residents represents an extraordinary social and political experiment. Called by some a “practical utopia,” Singapore has had a government that lives by master plans and metrics. It has set and met goals of creating affordable housing and home ownership and has consistently achieved near-full employment in standards that are unequaled anywhere in the world.

SOUTHEAST ASIA + TROPICS

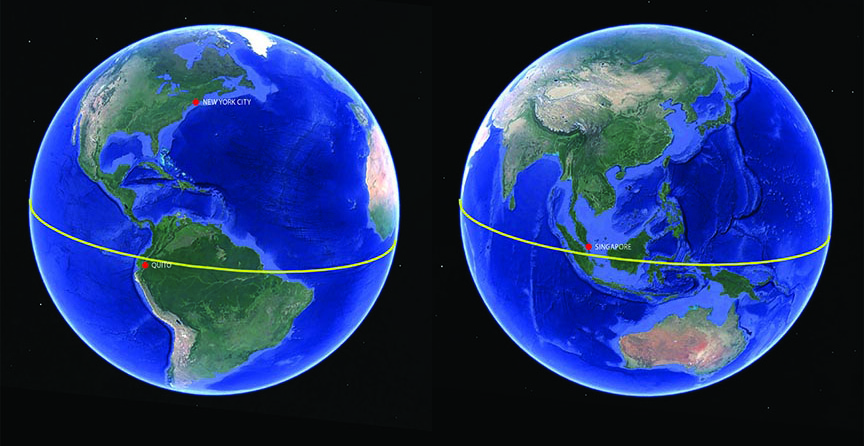

Google Earth

When it’s midnight in New York City, it’s noon in Singapore a calendar day ahead. Singapore lies on the opposite side of the globe, near the equator in the Eastern Hemisphere and on the other side of the International Date Line.

Köppen-vereinfacht

Köppen-vereinfacht

Ringing the equator are the tropics – regions of the world where the sun remains directly overhead at noon throughout the year, resulting in a hot climate with little change in seasons. In the Western Hemisphere, tropical regions are centered mainly in Ecuador, Colombia, and Brazil: in the Eastern Hemisphere, the tropical zone encompasses the islands of Indonesia, the Philippines, Malaysia, and much of Southeast Asia.

The bright green areas of the map on the left indicate tropical areas where sun, rain, and humidity maintain rainforest-like conditions year-round. At the tip of the Malay Peninsula, Singapore experiences temperatures averaging between 88 degrees Fahrenheit /31 Celsius during the day and 74 F /23 C at night. Humidity levels are equally high, between 70 to 90 percent. Rainfall is less consistent, with weather varying between strong sunshine and days of heavy rain brought on by the monsoon season.

Google Earth and The Skyscraper Museum

SINGAPORE SKYLINE

ourdaysabroad.wordpress.com

When the British established a port at Singapore in 1819, they settled at the mouth of the Singapore River and the Marina Bay. Advantageously located for international trade, this area would become the commercial center of the colony. Today, the Central Business District (CBD) or Downtown Core occupies the same space, about one square mile.

As an independent city-state, Singapore has grown into a center of global commerce and finance and a major transport hub. It has been named the “easiest place to do business” by the World Bank for ten consecutive years; the most “technology-ready” nation by the World Economic Forum (WEF); the world’s third-largest foreign exchange center; fourth-largest financial center; third-largest oil refining and trading center; and, since the 1990s, one of the top two busiest container ports.

Singapore City Skyline, 2010, Wikimedia Commons.

The business and financial center of Singapore’s strong economy is concentrated in skyscrapers in the Downtown Core. Built mostly since the 1990s, these towers follow the familiar forms and aesthetics of Western glass curtain-wall buildings, enclosed and climatized. The skyline is dense, with most building heights ranging between 225-250 meters (738 to 820 feet). The skyline is constrained by code, with the maximum height allowed by the air-traffic control standards being 280m / 919 ft.

The modern skyline creates a sharp contrast to the low-rise, traditional shophouse buildings of Chinatown that survive, protected as heritage conservation districts, near the Downtown Core.

MONUMENTALITY + MEGASCALE

Marina Bay Sands, Singapore, 2014, Wikimedia Commons.

By its sheer size and iconic form, rising above Marina Bay between the downtown core and the sea, the Marina Bay Sands has become a new symbol of Singapore as a center for tourism. Developed by the Las Vegas Sands, the economic engine of the project is the hotel, casino, and convention center, but the complex includes a massive mall, a museum, theatres, restaurants, a skating rink, and more.

Designed by architect Moshe Safdie, Marina Bay Sands is a simple, monumental gesture: three pairs of 55-story hotel towers, with slight variations in profile, have splayed legs that form a soaring linear atrium connecting the complex at its base. The three skyscrapers, which together house more than 2,500 hotel rooms, support a surf-board shaped platform that bridges the towers and cantilevers, thrillingly, 220 feet (67 meters) over thin air. The rooftop terrace includes an “infinity” swimming pool for the hotel and the tourist attraction the Sands SkyPark, an observation deck and restaurants.

Completed in 2010, the complex is the world’s most expensive stand-alone casino property, with costs, including land, of $8 billion Singapore dollars (nearly $6 billion USD).

MASTER PLANS + METRICS

Singapore is a self-proclaimed “Garden City," not simply for its endless growing season, but by political design. Introduced in 1967 by then Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew, the Garden City vision sought to transform Singapore into a place with abundant greenery and a clean environment, both to make life more pleasant for its people and to signal that a well-organized city, free of litter, was a good destination for tourists and foreign investments. The commitment to a green city was first developed in tree-lined boulevards, new parks, and recently in building regulations that encourage incorporating greenery and public space into multiple levels of the urban environment.

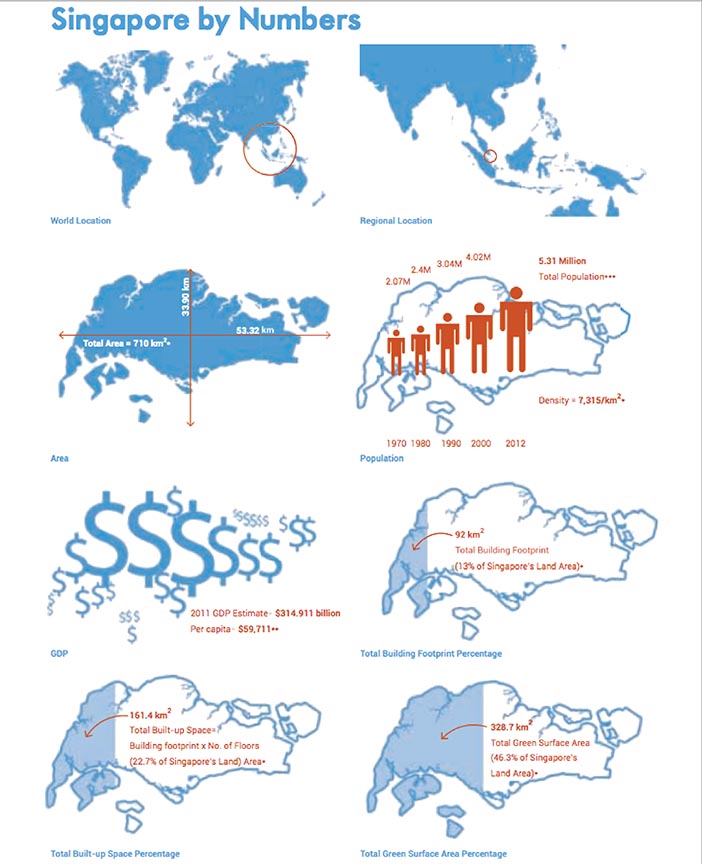

Singapore’s small land area, now enlarged by landfill to 719 square kilometers – 278 square miles, as compared to New York’s five boroughs at 304 square miles – and its constantly growing population, now around 5.5 million, has forced the government to address problems of urban density. The limited land and water resources have necessitated policies of environmental sustainability. Recently, the government has focused on green building strategies with the Green Mark rating system, which has reduced energy and water use while incorporating more greenery into new and existing buildings. Comparing the graphics of total built-up space and total green surface area emphasize how effective these initiatives have been.

SINGAPORE HOUSING

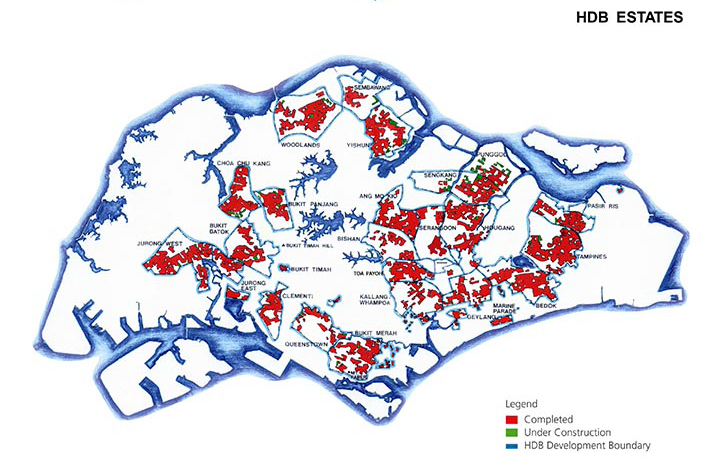

“Location of HBD Developments,” HBD Annual Report, 2013/2014.

Housing in Singapore is divided between two markets: luxury real estate investments for the wealthy and the far-larger segment of homes for all other classes built under government-sponsored programs of the Housing Development Board (HBD). In 2015, 82 percent of Singaporean residents lived in some form of public housing, and 90 percent of those own their homes.

To accommodate the densities necessary to manage Singapore’s limited land and growing population, the Housing Development Board early on embraced the high-rise typology and the goal of a garden city. In the 1960s, the HDB tackled the housing crisis with a comprehensive approach to town planning with production organized by the HDB and actual construction carried out by private contractors. Laid out according to master planning, towns of approximately 650 hectares were to accommodate up to 250,000 people, with half the land reserved for residences and the other half for facilities to support the town.

In 1973, the tallest public housing block reached 20 stories, while in 2005, nearly half of residents lived between the fifteenth and the thirtieth floor and the highest public housing buildings were 30 stories. The average height in 2007 was 12 stories, but more recently, buildings of 30 to 40 stories have become common.

VERTICAL DENSITY

Bottom: The Pinnacle@Duxton, Zhang Wenjie (Flickr), December 2011

Since the 2000s, the Housing Development Board has continued to evolve its goals of creating a wide range of affordable apartments, while also incorporating new standards for sustainability and social policy. The aim of improving living spaces and community amenities has led to some high-profile architectural commissions.

Chief among these was the international competition in 2001 for Duxton Plain, an area near the concentrated skyscrapers of the CBD and the low-rise shophouses of Chinatown in an area that had been home to some of the earliest public housing. The HDB’s intent was to establish a new model for a taller and more dense development that would rejuvenate the district with an infusion of young families who wanted to enjoy the conveniences of the central city. The site was tight – only 2.5 hectares (about 6 acres) – and the plot ratio of ground area to built floor space was 9:1, about three times the average for HDB housing.

The winner, selected by a distinguished jury from the 202 entries, was the design of a young Singapore firm, ARC Studio Architecture + Urbanism, who proposed an open, serpentine arrangement of seven linked 50-story towers that were dramatically connected by a series of sky bridges at the 26th floor and roof level. The bridges created continuous gardens and exercise and recreation spaces for the community, which in total comprised 1,848 apartments.

WOHA submitted an entry to the Duxton Plain competition which proposed a tight cluster of towers that would create shaded interior courtyards at eight levels. Although the project was unbuilt, the idea of stacked shared gardens became the seminal idea developed in many of WOHA’s projects, including the Met and Skyville.

TROPICAL ARCHITECTURE

The term “tropical architecture” may bring to mind tree houses and bamboo screens, but the challenge of building high-rise buildings for business and housing in hot and humid climates requires models that depart from the dominant conventions of international architecture of temperate zones where the need to heat or cool in different seasons dominates the design of curtain walls and mechanical systems,

One Western architect who studied tropical architecture was Paul Rudolph, who in the 1970s and ‘80s designed buildings for the hot climates of Florida, California, Hong Kong, and Singapore – including The Concourse, illustrated here in Rudolf’s handsome drawing. As built in 1987, the Concourse was a mixed-use development that includes a 41-story office tower, a three-level retail podium, and nine stories of serviced apartments. The design illustrates Rudolph’s theory of the “Tropical Skyscraper” in its use of “piloti” columns that lift the tower above the ground plane, solar shading, wide overhangs, and communal gardens. The stilts that raise WOHA’s hotel-and-office complex PARKROYAL on Pickering high above the street and support an undulating series of landscape-like layers show the influence that Rudolf had on their work.

Other features of tropical architecture include the use of shading, breezeways, abundant gardens, and other strategies that use passive environmental techniques to cool buildings without air-conditioning and other energy-dependent systems.

MEGA CITIES

Of the world’s thirty largest megacities – metropolitan agglomerations with a population of 10 million or more –

ten are located in Southeast Asia and South Asia. Many of the most populous, such as Jakarta, Indonesia, with 30 million residents, and Manila in the Philippines with 20 million, occupy coastal flood plains where their populations are especially vulnerable to environmental extremes. Bolded below and illustrated on the map are the megacities located across all regions of Asia.

GARDEN CITY MEGA CITY

Since 2001, WOHA’s buildings in Singapore have established a series of built prototypes for housing that is dense, highly social, and environmentally sustainable. Their buildings are both practical and theoretical and can be seen as a series of over-lapping case studies that can be applied across tropical zones where cities are growing faster than architects, planners, and governments can manage.

In their new book GARDEN CITY MEGA CITY – to be published in spring 2016 – WOHA applies their studies and prototypes to the urgent issues facing the rapidly urbanizing mega cities of the tropics.

Taking a stance more strident and polemical than in their earlier work, the book identifies procedures – architectural, environmental, infrastructural, social, and governmental –and proposes strategies that should be implemented to avert the systemic collapse of the overloaded cities.

Bottom: Jakarta, 2004 Wikipedia.

The book is a collaboration that marries the work of WOHA with a commentary by Patrick Bingham-Hall, a writer and photographer who has worked closely with the architects for many years. In the words of Bingham-Hall:

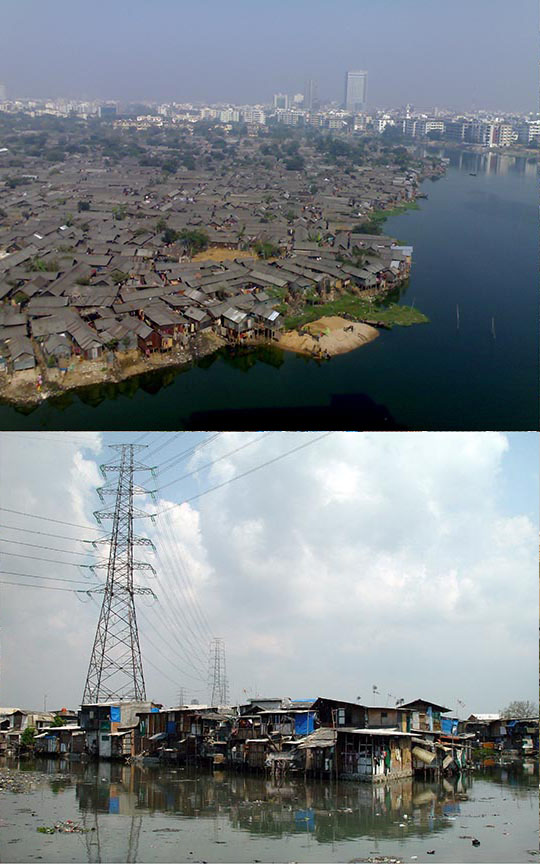

“The essential problems that plague the Asian mega cities are the same as those generated by unexpected and uncontrolled urban expansion throughout history… water supply, sanitation, flooding, overcrowding, slums, air quality, and transportation failure. Unless something is done quickly, the most predictable crisis facing 21st century civilization is the des- cent of the new Asian mega cities into a state of potentially terminal dysfunction."

The conditions of slum housing in Dhaka (top) and Jakarta are revealed in these characteristic photographs.

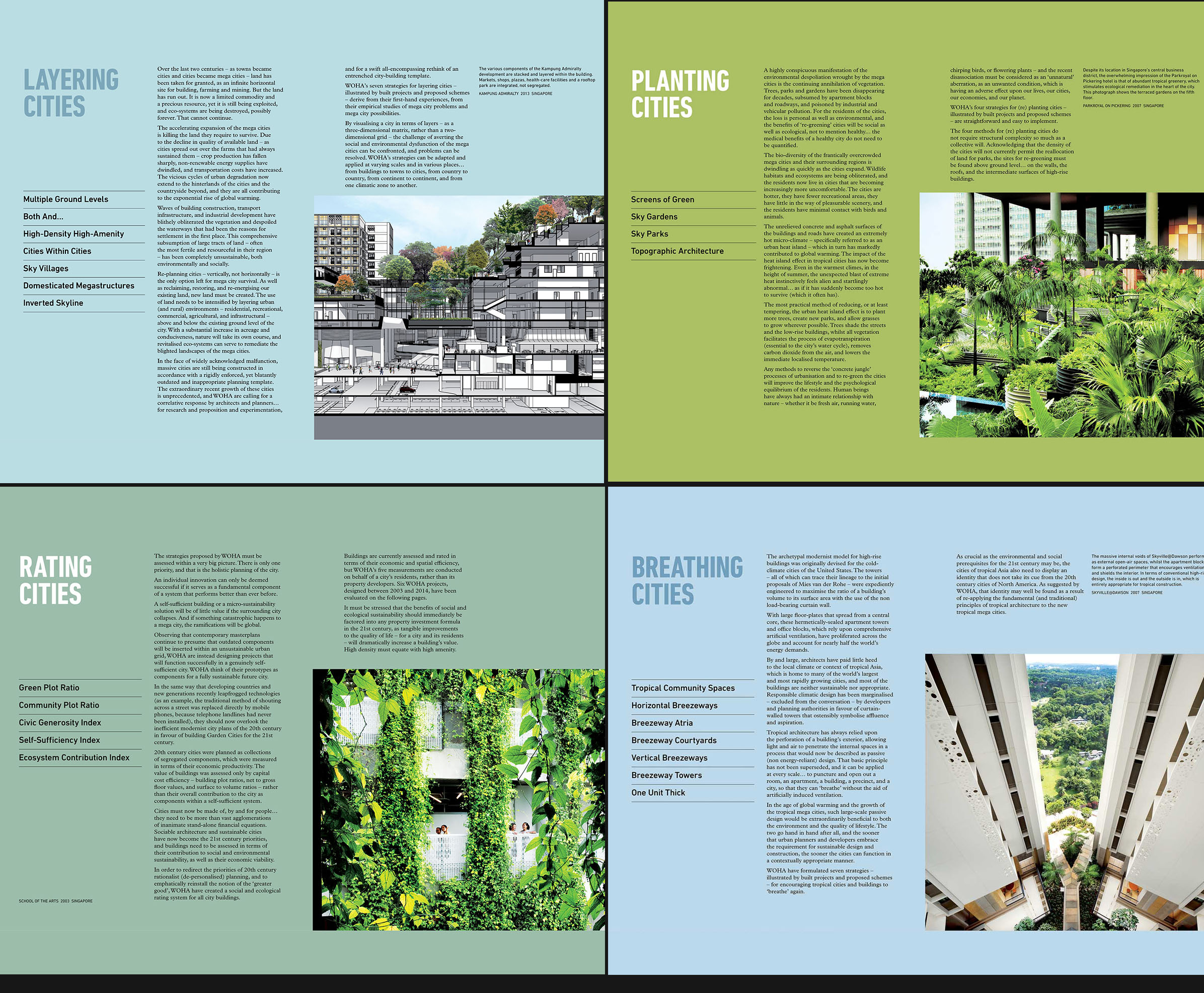

The GARDEN CITY MEGA CITY book has two covers – the one in black and orange above that seems to warn of apocalyptic pollution and a second, here in a verdant green view of a PARKROYAL terrace – that contrast possible urban futures. WOHA uses case studies of their own buildings to illustrate how passive (non energy-reliant) design strategies and government regulation and metrics can offer salvation. Displayed below are four pages from the book that describe Layering Cities, Planting Cities, Rating Cities, and Brea-thing Cities. A quote from the last topic notes: "WOHA have formulated seven strategies – illustrated by built projects and proposed schemes – for encouraging tropical cities and buildings to ‘breathe’ again." These strategies, which are noted throughout the panels of the exhibition, are Tropical Community Spaces; Horizontal Breezeways; Breezeway Atria; Breezeway Courtyards; Vertical Breezeways; Breezeway Towers; One Unit Thick Buildings.