The Skyscraper Museum is devoted to the study of high-rise building, past, present, and future. The Museum explores tall buildings as objects of design, products of technology, sites of construction, investments in real estate, and places of work and residence. This site will look better in a browser that supports web standards, but it is accessible to any browser or Internet device.

EXPERIENCING THE WOOLWORTH

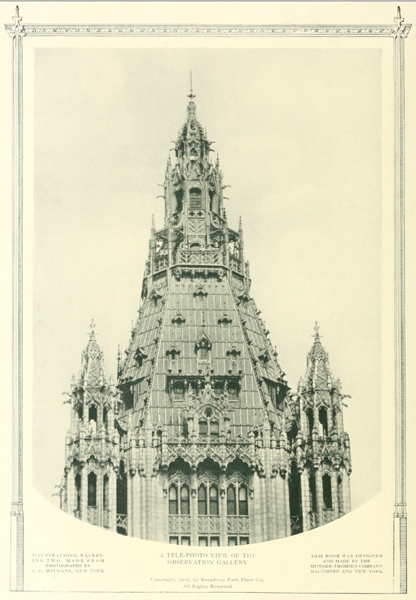

The Woolworth Building's pinnacle observatory was promoted as a "wonder to tourists." By 1916, it drew more than 100,000 people a year from over 60 countries. To reach the top, sightseers purchased tickets for 50 cents (equals $11.60 today) at a booth near the Barclay Street entrance, then, shuttled in a high-speed elevator to the 54th floor, where they could buy postcards, souvenirs, and ice cream at the "highest retail location in the world." To ascend to the 58th-floor outdoor terrace, they could take a six-person circular glass elevator or climb a spiral stair.

From this 750-foot high aerie, the city lay below in a thrilling panorama. As described in the illustrated souvenir guidebook Above the Clouds and Old New York (1913) by H. Addington Bruce:

The Cathedral of Commerce. From the Skyscraper Museum Collection.

"Looking down on the thousands of great structures, the wonderful bridges that span the East River, the beautiful parks, the great steamers berthed at piers along the rivers, one realizes the grandeur and vastness of the metropolis. The serried peaks made by the giant buildings, towers, church steeples all seem to contend with each other for the distinction of "highest and greatest." But above them all rises the Woolworth Building, calm and unassailable."

Equally moved to eloquence in a different media was the American vanguard artist John Marin, who celebrated the Woolworth Building as a touchstone of modernity in innumerable paintings, drawings, and prints. His etching "The Dance" shows the skyscraper's verticals tense with energy-"pushing, pulling, sideways, downwards, upwards"-in the artist's words, as if to free itself from the city's historical surroundings. For Marin, the building's kinetic energy signified the modern city's dynamism and futurity.

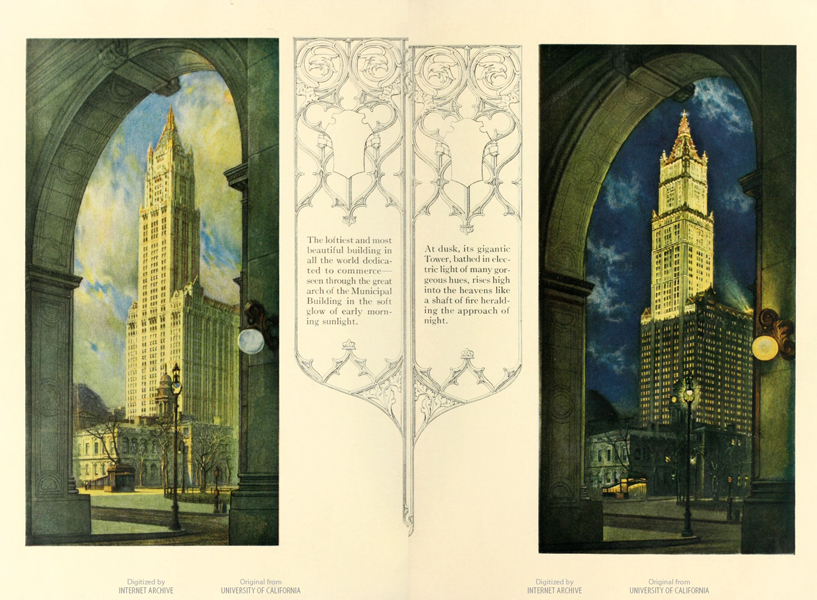

The Cathedral of Commerce, 12 - 13. From the Skyscraper Museum Collection.

Nothing bespoke the modernity of the Woolworth Building more than the night illumination of the tower that was inaugurated on New Year's Eve 1914. According to the World's Advance, the tower "burst forth from the black night one giant shaft of uniform light crowned with a great scintillating jewel...the greatest permanent lighting spectacle in the world." Floodlights equaling 12 million foot candles washed evenly across the façade. In the lantern at the tower's tip, Woolworth and Gilbert had engineers design a cluster of twenty 1,000-watt lamps to create "an immense ball of fire." Scientific American reported "a great crystal of flaming light" that caused "the other lighting spectacles of the metropolis to fade away before it."

Without spelling out the name "Woolworth"-or even crowning the tower with "Ws", as once was considered-the skyscraper functioned as an immense sign, and it outshone its contemporaries and competitors.