The Skyscraper Museum is devoted to the study of high-rise building, past, present, and future. The Museum explores tall buildings as objects of design, products of technology, sites of construction, investments in real estate, and places of work and residence. This site will look better in a browser that supports web standards, but it is accessible to any browser or Internet device.

Corbels of the Woolworth

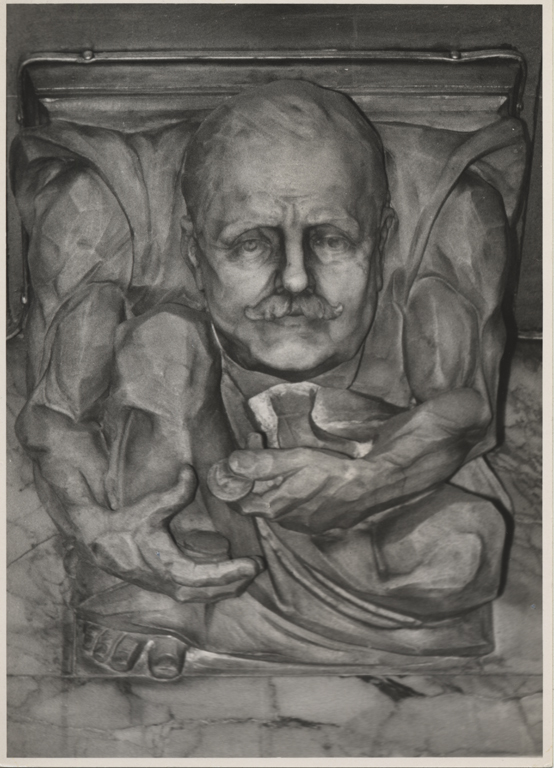

Frank Woolworth (c) John Bartelstone

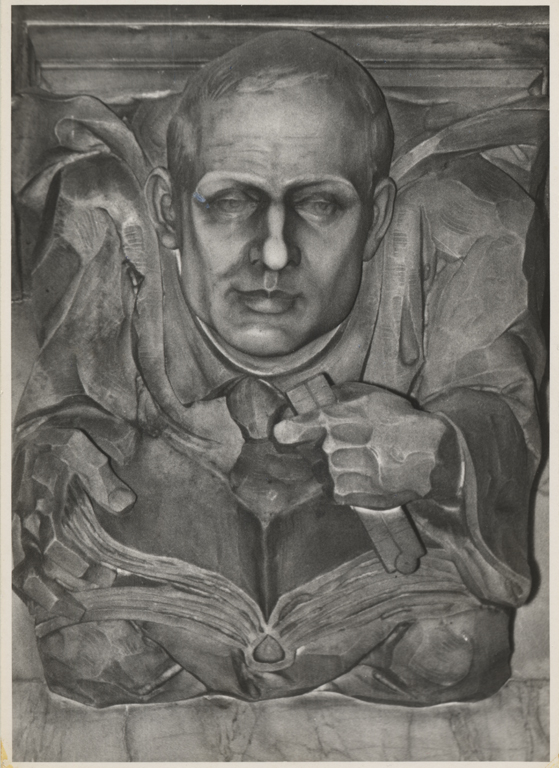

In its proportions and scale, the Woolworth Building's lobby-arcade recalls a Romanesque cathedral nave. But its ornamental details and glittering mosaics create an atmosphere of fantasy that abounds with human interest in its own right. In few features is this more evident than in the corbel sculptures that represent each individual who contributed to the realization of the skyscraper. Based on caricature sketches by Thomas R. Johnson, they were judged by one critic as "delightfully gay exaggerations without being the least unkind." Each brandishes an attribute--the engineer Gunvald Aus, for instance, is shown inspecting a steel beam--that suggests the uniqueness of his role in the project.

The juxtaposition of the corbel sculptures within a single space points to the importance of collaboration in the realization of the Woolworth Building. At least one contemporary credited Cass Gilbert for the skill with which he chose his collaborators: "the successful execution of his work lies largely in the success with which he chooses them and secures their loyal cooperation." But Gilbert in turn credited Frank W. Woolworth for inspiring the project's spirit of collaboration, who he described as "so sympathetic, so enthusiastic" that "he enlisted the enthusiasm of all connected with the work."

Woolworth's vision for his skyscraper was broad and populist, given that the F. W. Woolworth Company's profits derived from the thousands of sidewalk shoppers who crowded the main streets of small towns across America. So, it is not surprising that he anticipated those shoppers--along with tourists from around the world--would visit the lobby and take pleasure in the spectacle of mosaic and sculptural detail. For this reason, he had Gilbert use every imaginable device--the corbel sculptures included--to heighten the skyscraper's popularity. He aimed to win over not the few, but the many.

Frank Woolworth, Collection of The Skyscraper Museum, Gift of Andrew Alpern

Frank Woolworth, the noted retailer and founder of the F.W. Woolworth chain of five- and ten-cent stores, is shown counting the nickels and dimes on which he built his business, suggesting his frugality, business acumen, and the stringency of his "cash only" policies. But Woolworth's interests also extended beyond such day-to-day financial realities. An inveterate tourist, he took yearly buying trips to Europe, seeking out noted European capitals and historic landmarks, among them the Paris Opera, the Eiffel Tower, and the great cathedrals. He attended operatic performances in cities across the European continent, cultivating a ritualistic devotion to music, scenography, and show. All would be of the highest importance to his spectacular landmark skyscraper--not only for how he conceived it as a work of architecture, but also for how he envisioned its role within the 20th-century metropolis.

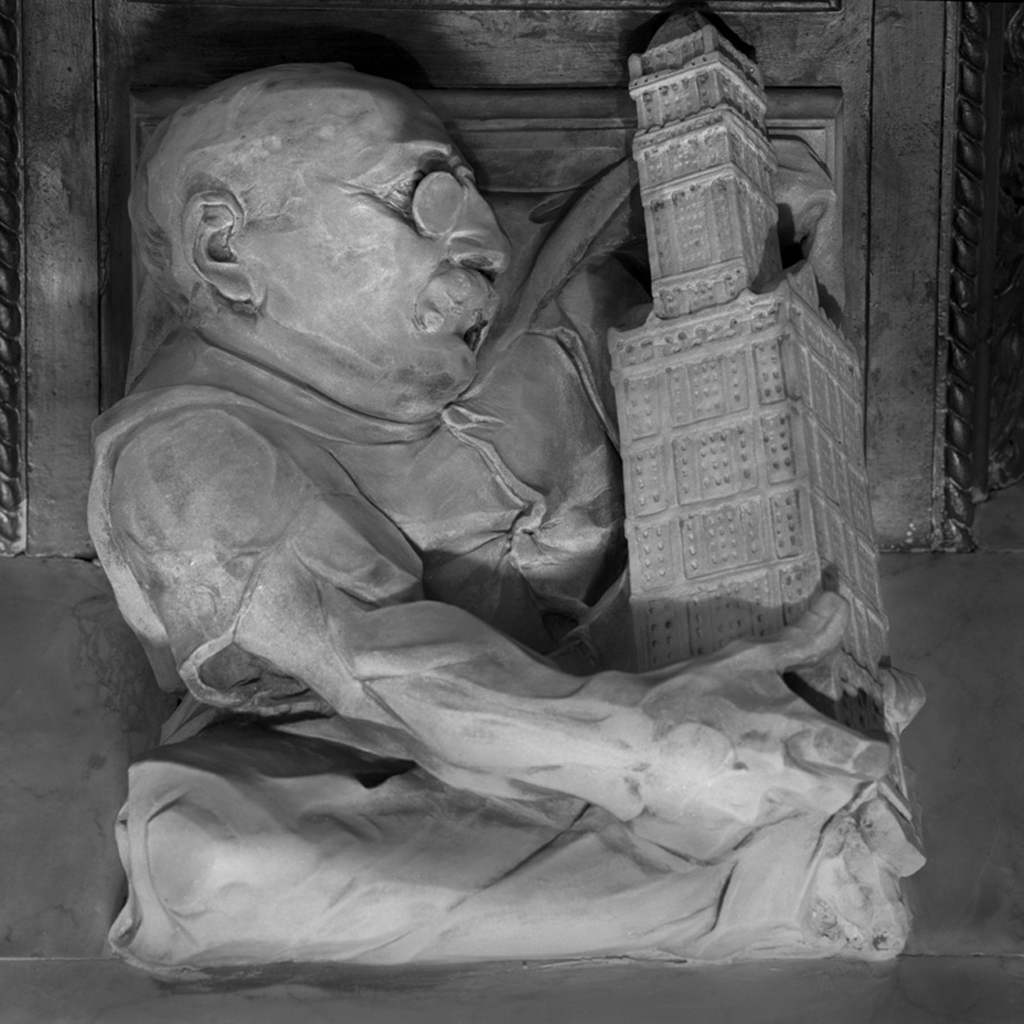

Cass Gilbert, the bespectacled architect, carries a model of his design for the skyscraper, 2012, Courtesy of John Bartelstone (c)

Cass Gilbert, the Woolworth Building's architect, carries a model of his design for the skyscraper. Gilbert's practice, nationally known, had been headquartered in New York since 1899. Gilbert was reputed for his United States Custom House and West Street Building, both of which Woolworth admired. He had studied at MIT, traveled in Europe, apprenticed with McKim, Mead & White in New York, an in the early 1880s established a practice in St. Paul, Minnesota prior to returning to New York. While remembered for his monumental works of architecture, noted among them the Minnesota State Capitol and the United States Supreme Court, Gilbert took an intrinsic interest in the skyscraper as a modern building type. Gilbert's architecture is reputed for its scenographic composition, fine proportions, richness of color, and abundance of ornament.

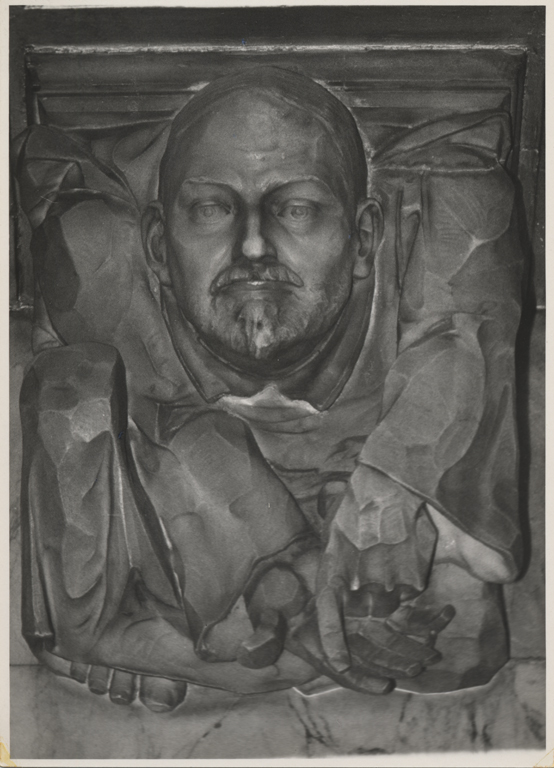

Gunvald Aus, the project's structural engineer inspects a steel beam. The Norwegian emigre set up practice in New York in1902 and had previously collaborated with Gilbert on the West Street Building, 2012, Courtesy of John Bartelstone (c)

Gunvald Aus, the project's structural engineer, is shown inspecting a steel beam. Having emigrated from Norway to the United States in 1883 after training at the Polytechnic Institute in Munich, Aus had worked as a bridge designer prior to setting up his practice in New York in 1902. Before he designed the Woolworth Building’s concrete pier foundation and steel superstructure, Aus collaborated with Gilbert on the West Street Building. Aus's professional contribution to the Woolworth Building supported Woolworth in his aim of achieving an eye-catching, theatrical, and publicity-generating height. But it was also essential to the aesthetic success of Gilbert’s design. Aus's portal arch system of wind bracing for the tower in particular made possible the exterior's impression of a dazzling verticality coupled with a screen-like openness and ethereality. Without Aus's ingenious structural scaffolding of steel, Gilbert would have been hard-pressed to fabricate the Woolworth Building's Gothic imagery.

Lewis E. Pierson, Collection of The Skyscraper Museum, Gift of Andrew Alpern

Lewis E. Pierson, President of Irving National Exchange Bank, operates a ticker tape machine, the tape of which is inscribed with miniature Woolworth Buildings. This suggests the profits derived from the bank’s joint stock ownership in the Broadway-Park Place Company, the corporation established by Pierson and Woolworth to finance the Woolworth Building's construction as well as to oversee its performance as a rental property. Woolworth's relationship with the bank began as a depositor and subsequently, the bank facilitated the expansion of his chain. In 1907, Woolworth orchestrated a merger between New York National Exchange Bank, on whose board of directors he served, and Irving National Bank, to create the new Irving National Exchange Bank, one of the most powerful banks in New York. Importantly, Irving National Exchange Bank also housed Woolworth’s own staggering accumulation of capital.

Louis Horowitz, Collection of The Skyscraper Museum, Gift of Andrew Alpern

Louis Hororwitz, President of the Thompson-Starrett Company, the builder of the Woolworth Building, is shown making a telephone call. The telephone, still new at the time, sped communications between Horowitz and Thompson-Starrett's superintendent at the Woolworth Building's construction site as well as among the foremen representing each building trade. The Thompson-Starrett Company had recently risen to dominance in the construction industry as a "national builder." Along with the Fuller Company and others, it had reorganized the industry under the single-contract system. Aiming to complete large-scale projects in record time, Horowitz emphasized rationalization, efficiency, and financial control throughout the construction process. This Woolworth highly valued, given that he found it essential for the project's builder to "have an organization back of him which was thoroughly adequate and had reached a maximum of efficiency."

Edward Hogan, Collection of The Skyscraper Museum, Gift of Andrew Alpern

Edward Hogan, the Broadway-Park Place Company's real estate agent, counts on his fingers, perhaps negotiating a sale or finalizing a deal. Hogan had acquired the site for Woolworth's French Renaissance chateau on Fifth Avenue in 1900 and subsequently Woolworth enlisted his assistance with acquiring the Woolworth Building's site at Broadway and Park Place. Hogan may have also introduced Woolworth to Cass Gilbert. After the completion of the Woolworth Building, Hogan served as the property's rental agent, relying heavily on advertising as well as newspaper publicity to promote its offices to tenants.

Thomas R. Johnson, Collection of The Skyscraper Museum, Gift of Andrew Alpern

Thomas R. Johnson, the lead designer in Cass Gilbert's office, is shown puzzling over a blank sheet of paper, perhaps considering his next step in the process of developing the Woolworth Building's Gothic imagery. Taking his cues from Gilbert's sketches, Johnson produced the project's several large-scale perspectives, which incorporated his own refinements of Gilbert's conceptual designs, beginning with the project's origins in a 20-story building and concluding with the widely published 55-story, 750 feet high final design for the highest skyscraper in the world. Johnson’s perspectives, colorful as well as precise, appealed to a broad audience of observers—among them the readers of the city's newspapers. They aimed to convince all viewers of the skyscraper's aesthetic distinction as well as its structural plausibility. Later in the project's development, Johnson oversaw the production of the design's intricate ornamental motifs, guiding the office's junior designers and draftsmen in refining Gothic spandrels, canopies, tourelles, buttresses, pinnacles, and gables. He approved shop drawings produced by the Atlantic Terra Cotta Company's in-house draftsmen and subsequently, Donnelly & Ricci's models for the project's terra cotta, limestone, and copper.

William Sunter, Collection of The Skyscraper Museum, Gift of Andrew Alpern

William Sunter, Thompson-Starrett’s superintendent, pours over a thick project schedule with a ruler in hand. Gilbert called him "the most efficient man on the job" because of his strict management and enforcement of the schedule.