The Skyscraper Museum is devoted to the study of high-rise building, past, present, and future. The Museum explores tall buildings as objects of design, products of technology, sites of construction, investments in real estate, and places of work and residence. This site will look better in a browser that supports web standards, but it is accessible to any browser or Internet device.

Introduction

Photograph � Christopher Hall

Photograph � Christopher Hall

"From farm to factory" is shorthand for urbanization --the process that paralleled the shift from early industrial, water-powered mills, and workshops to Machine-Age dynamos of mass production. From the mid-19th century, standardized parts and mechanical systems transformed both manufacturing (Latin roots: manus (hand) and facere (to make), literally "handmade") and society. Urban populations swelled to meet the labor demands of factories. In the competition for expensive city land, buildings expanded upward, either to house vertically integrated systems of production or to multiply floors of rentable space.

Early 20th-century engineers and architects rationalized factory processes and design based on principles of time-motion studies and integrated manufacturing systems. Emulating the utilitarian forms of industry, Modernists such as Le Corbusier and Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius embraced glass, steel, and concrete, undecorated walls, and open spatial volumes as elements of a new aesthetic vocabulary. This exhibition examines the historical origins of factory architecture, its 20th-century status as an icon of modernity, and possible futures for new and reinvented urban factories.

Since the mid-20th century, industry has shifted away from city centers, first to edges and suburbs, then to other shores. Once rooted by natural power, transport systems, or an abundance of workers, today all manufacturers compete in a globalized marketplace where cheaper labor and shipping have shifted the economics of production. De-industrialized cities such as New York, with a substantial inventory of older factory structures, must find new strategies to maintain manufacturing sectors. Although many former factories have been reinvented as residential lofts, art studios and galleries, and spaces of consumption, this exhibition is not focused on adaptive reuse. Instead, it explores new directions where-- given today's advanced computer technologies, material innovations, and the demand for cleaner and "greener" industries-- architects, engineers, and urban designers have the potential to integrate industry with everyday life, creating self-sufficient and sustainable cities.

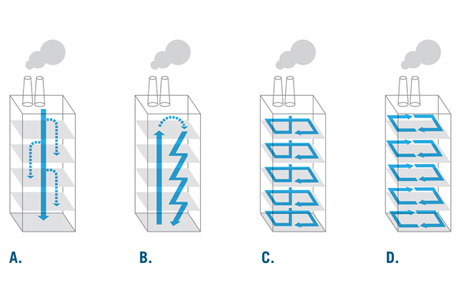

Factory TypesA factory is a space for the making, shaping, or assembly of things. Conceptually, and in practice, there are two principal types of vertical urban factories: integrated and layered.

Integrated In the integrated type, the production flows from top to bottom, or vice versa, as components or raw goods are mixed, sorted, or assembled by workers or machines, then carried by conveyors or chutes to the end of the process for transport to market. The gravity method of production, which was later mechanized (type A), is most common in a multi-story building of a single company, such as Henry Ford's Highland Park automobile factory in Detroit. The processing can also move from bottom to top (type B), as at the Fiat Lingotto factory, in Turin, Italy.

Courtesy of Prof. Eberhard

Courtesy of Prof. Eberhard

Layered In the layered type, there are separate stacked floors occupied by one or more companies sharing common areas and services such as lobbies, elevators, and power. While the building is multi-storied, the processing may be confined to all, or part of a single floor, or expand to adjacent floors (types C and D). Lofts in New York's Garment District or Hong Kong's high-rise factories concentrate this generic type. Like office buildings, these production spaces are usually erected by real estate developers as rental properties-- commodities of space-- rather than by factory operators who integrate the building with their machinery.