The Skyscraper Museum is devoted to the study of high-rise building, past, present, and future. The Museum explores tall buildings as objects of design, products of technology, sites of construction, investments in real estate, and places of work and residence. This site will look better in a browser that supports web standards, but it is accessible to any browser or Internet device.

CHRYSLER BUILDING

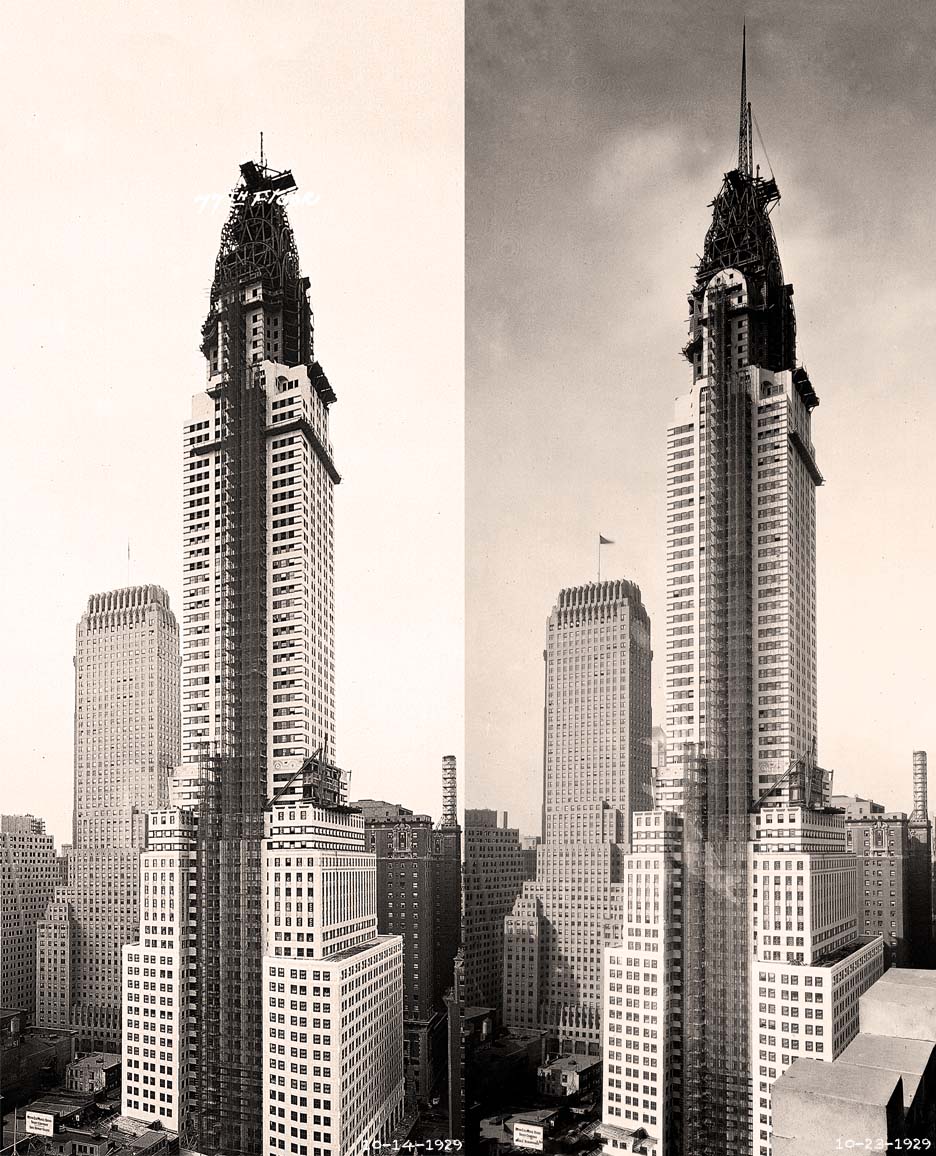

Left: Chrysler Building, October 14, 1929, Courtesy of David Stravitz

Right: Chrysler Building, October 23, 1929, Courtesy of David Stravitz

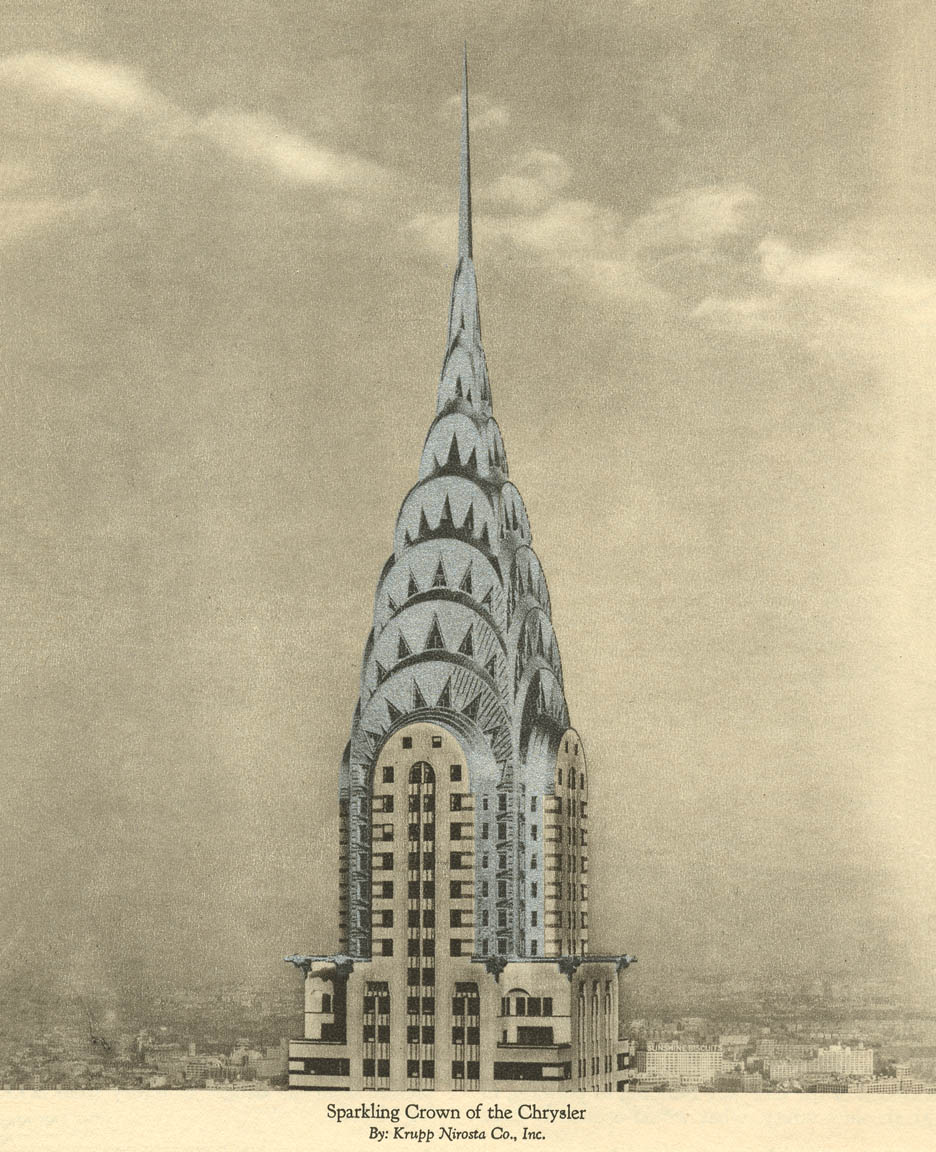

The most fanciful and famous top of all of Manhattan's ornamental beauties is certainly the Chrysler Building, a quintessential expression of Jazz-Age New York. Its flashy modernism was communicated through the stainless steel crown with its crescendo of seven scalloped domes and spiky triangular windows. The needle spire stretched its height to 1,046 ft., which won it the title of tallest building in the world from 1930 to 1931, until the completion of the Empire State Building.

The project began in 1927, when entrepreneur William H. Reynolds, known for developing Dreamland at Coney Island, hired architect William Van Alen to design a speculative skyscraper, to be called the Reynolds Building, for a site on the northeast corner of Lexington Avenue and 42nd Street. The project was planned to rise 67 stories and 808 feet.

In October 1928, the land lease and plans were acquired by the automobile magnate Walter P. Chrysler, who was in the news as Time Magazine "Man of the Year" for 1928. Chrysler developed the tower as a personal project, not as a company headquarters: no corporate funds were used in its financing or construction. Van Alen altered the scheme to reflect his new client, and the front page of the New York Times reported on October 17, 1928 that Chrysler's 808-foot tower would have 65 floors of offices and, above, a duplex apartment, and a "three-story observation dome constructed of bronze and glass, culminating in a spire."

The steel framework of the tower was completed in September 1929. During that year, the announced height had grown to 905 feet, according to newspaper accounts, although plans had been made in secret for an addition that would reach to 1,046 feet. This altitude would exceed the announced height of its rival 40 Wall Street, which was topping out that same month at 927 feet to the tip of its needle spire.

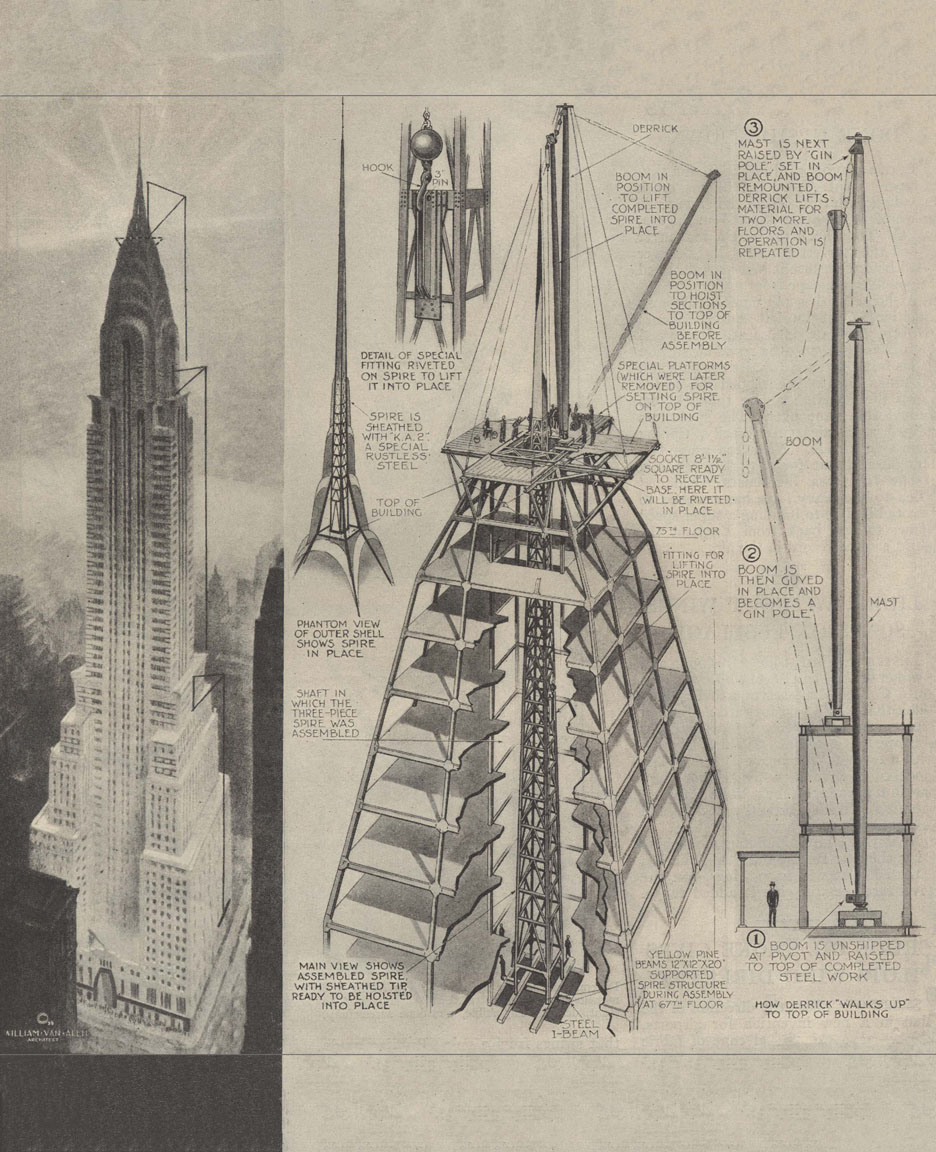

CHRYSLER CONSTRUCTION

The progress photographs and construction diagram illustrate the remarkable feat of erecting of the top of Chrysler Building and help to clarify details about the often exaggerated story of a rivalry: a "race to the skies" between two skyscrapers and two architects, William Van Alen and his former partner Craig Severance, with Yasuo Matsui, the architect of 40 Wall Street.

The boom in skyscraper construction in New York from the mid-1920s was at once reality-based in the white-hot investment economy and also a real estate bubble. Dozens of 30- and 40-story buildings were added to the Manhattan skyline both downtown and in midtown. To stand out from this crowd, a few taller towers were announced. The most ambitious were the Chrysler Building and 40 Wall Street, both of which were to surpass the 792-foot height of the Woolworth Building spire, which was still the city's tallest building.

The more lofty title of "world's tallest building" belonged to the 1889 Eiffel Tower in Paris at 300 meters/ 986 feet. This was apparently the marker that Walter Chrysler had in mind when he authorized the attenuated new design for a 77-story building with Van Alen's "vertex," the 7-scalloped domes of the tower's stainless-steel crown.

Both the Chrysler Building and 40 Wall Street topped out in the fall of 1929, and newspapers began to pay attention to the "race." As the progress photos (above), on 10/14/29, only a truncated tip of the needle poked out of the dome. On October 23 - the very day before the stock market crash that signaled the beginning of the Great Depression - a 185-foot steel spike was hoisted from within the vertex dome to claim a vertical height of 1,046 feet. Incredibly, the work took only 90 minutes: it would have made for great film footage or photojournalism - if only the press had been alerted.

In fact, it was only after 40 Wall Street topped out in November that the superior height of the Chrysler Building was promoted to the press. The scaffolding that encased and shrouded the dome so the workers could finish the stainless steel cladding stayed in place until the spring of 1930 when the gleaming spire slowly emerged from its chrysalis.

THE VERTEX

Lattice-steel framework of the spire and needle of the Chrysler Building, November 1929. Courtesy David Stravitz.

In the article "The Structure and Metal Work of the Chrysler Building" in the October 1930 issue of Architectural Forum, architect William Van Alen explained the design and construction of the tiered dome and "vertex."

A high spire structure with a needle-like termination was designed to surmount the dome. This is 185 feet high and 8 feet square at its base. It was made up of four corner angles, with light angle strut and diagonal members, all told weighing 27 tons. It was manifestly impossible to assemble this structure and hoist it as a unit from the ground, and equally impossible to hoist it in sections and place them as such in their final positions. Besides, it would be more spectacular, for publicity value, to have this cloud-piercing needle appear unexpectedly.

Therefore, the spire was fabricated and delivered to the building in five sections and assembled inside the dome. The drawings created for Popular Science Monthly in 1930, above, shows a cutaway diagram of the assembled spire, spanning seven floors of an open well within the steel skeleton ready to be hoisted into place.

A scaffolding of steel pipe draped with heavy wire netting was erected around the dome (and eventually the spire) to protect sheet-metal installers working on the building's ornamental terminus. Because of the curving shape of the dome's form, measurements for the sheet steel needed to be verified in the field. The bulk of the work was thus carried out in metalworking shops located on the sixty-seventh and seventy-fifth floors of the building.

CHRYSLER SPIRE

Below the 61st floor, the Chrysler Building was a fairly conventional office tower, with a shape that followed the setback formula required by the city's zoning law. Above the last setback and the stainless steel eagle-head gargoyles, though, both the program of the interior spaces and the architectural ornament entered the realm of the eccentric.

On floors 66 to 68, below the public observation deck (the second level of triangular windows), was the Cloud Club, a private dining and lounge space for executives who paid a $300 annual fee for membership to enjoy either the double-height dining room with Art Deco details or a more cozy Tudor lounge and “Old English” bar and grill. Walter Chrysler kept a private dining room with black etched-glass panels that looked north to Central Park. His offices in the tower, though, were outfitted in a baronial style of wood paneling and upholstered furniture.

In its exterior form and ornament, the scalloped dome and finial, which seems like a silver helmet on an almost-anthropomorphic “head,” has no precedent, nor any clear explanation. An unnamed critic wrote in the Architectural Forum in October 1930:

The Chrysler … stands by itself, something apart and alone. It is simply the realization, the fulfillment in metal and masonry, of a one-man dream, a dream of such ambitions and such magnitude as to defy the comprehension and the criticism of ordinary men or by ordinary standards.

The question arises: did the critic mean this singular dream was Chrysler’s or Van Alen’s? Most likely the former, because without an indulgent client, such an extravagant work would never have been realized. But Van Alen’s unfettered imagination seems far richer than Chrysler’s personal taste. The two men’s collaboration, however, ended in acrimony and a lawsuit over payments, and even after the Depression Van Alen had little work.

CHRYSLER OBSERVATORY

The 71st floor of the Chrysler Building was used as an observatory from 1930 to 1945. Visitors bought a ticket in the lobby and ascended by Van Alen’s colorful elevator car, patterned in precious woods, to the observation level. There they could circle the periphery through a corridor and vaults painted with a celestial ceiling of stars and golden rays, reminiscent of German expressionist film sets like the 1926 Metropolis. The architectural writer Eugene Clute described the space in Architectural Forum in October 1930:

The gallery follows the octagonal form of the perimeter of the tower and surrounds an octagonal space in which are grouped the elevators and various utility features. The ceiling is high. At points along the outer wall of the gallery, where heavy members of the structural steel slant inward from floor to ceiling, these members have been encased and the resulting form has been repeated upon the inner side of the gallery. This produces a series of openings which provide effective visits from one section of the gallery to another. Here, enclosed in a glass case, is Walter P. Chrysler’s box of workman’s tools with which he started his career. This gallery provides pleasant surroundings from which visitors may enjoy the remarkable views of New York and adjacent counties that can be had through the wide windows on every side.

The small triangular windows that were the result of the dome’s design, however, created odd angles for viewing the city below. The Empire State Building, completed a year later, with its outdoor spaces and unobstructed vistas, became the more popular elevated experience, and the Chrysler Building’s observatory continued to operate for just fourteen more years.