The Skyscraper Museum is devoted to the study of high-rise building, past, present, and future. The Museum explores tall buildings as objects of design, products of technology, sites of construction, investments in real estate, and places of work and residence. This site will look better in a browser that supports web standards, but it is accessible to any browser or Internet device.

WOOLWORTH BUILDING

Detail of the steel skeleton under construction, 1912.

Photograph by Bain News Service, Library of Congress.

Frank W. Woolworth, the five-and-dime store king, did not start out to build the world's tallest office building. The earliest drawings for the project in early 1910 depicted only twenty stories. But over the course of the year, with the encouragement and inspiration of architect Cass Gilbert, the client's ambitions grew, and their shared desire to erect a record-breaking tower became clear.

On December 20, 1910, Woolworth sent surveyors to determine the precise height of the tip of the Metropolitan Life Tower - then the world's tallest building - which he clearly intended to surpass. On January 20, 1911, The New York Times published an interview with Woolworth in which he boasted of his intentions to erect a 750-foot tower. By April, the final height of 792 feet was established and the project was promoted as the "world's greatest skyscraper."

While the height of the Woolworth Building can be precisely measured, the number of floors in the tower was open to interpretation and was variously reported by the owner and in newspapers as either 55 or 60 stories. At the opening ceremonies, Woolworth claimed the higher number. His new count apparently included short mezzanine stories within the tower - one within the pyramidal roof seen here as an unclad steel skeleton - and another in the lantern in the tower's pinnacle. A hand-written note of 1920 in the Cass Gilbert archives of the New-York Historical Society explained: "The owners of the building have numbered the pipe galleries, and they now call the building 60 stories high."

Exaggerating floor counts in skyscrapers has become a common practice, since higher numbers seem to carry additional prestige. Today, especially in the lavish new condominium towers in New York, inflating the floor count is widespread. For example, the 75 constructed floors of the billionaire roost One 57 is marketed by the developer as "90 stories of elevated living."

OPENING NIGHT

Eighty thousand incandescent bulbs illuminated the New York night on April 24, 1913, when the Woolworth Building opened with a ceremony as fantastic as the structure itself. President Woodrow Wilson pressed a button in the White House that simultaneously lit every interior floor and the brilliant tower beacon. In the lantern at the tower's tip, engineers designed a cluster of twenty 1,000-watt lamps to creating "an immense ball of fire." Scientific American described it as "a great crystal of flaming light" that caused "the other lighting spectacles of the metropolis to fade away before it."

Witnessed by multitudes and wired to press around the world, the opening celebration was a career-crowning achievement for the tower's owner, Frank W. Woolworth, who paid for the skyscraper with his personal fortune and took a hands-on role in every decision of its design and promotion. Dubbed the "Cathedral of Commerce" for its neo-gothic ornament and soaring silhouette, the lofty tower was both a marvel of early 20th-century technology and a masterpiece of the architectural arts. Years earlier, the architect Cass Gilbert had defined the skyscraper as "a machine to make the land pay." But with the Woolworth Building, he found an ideal client willing to elevate the tower beyond the realm of real estate to the status of a civic monument.

As a savvy marketer Woolworth justified the extra expense as effective advertising, noting that both the iconic presence of his tower on the New York skyline and its superlative height had immeasurable value. Indeed, today the Woolworth Building remains the city's most beloved and inspiring landmarks.

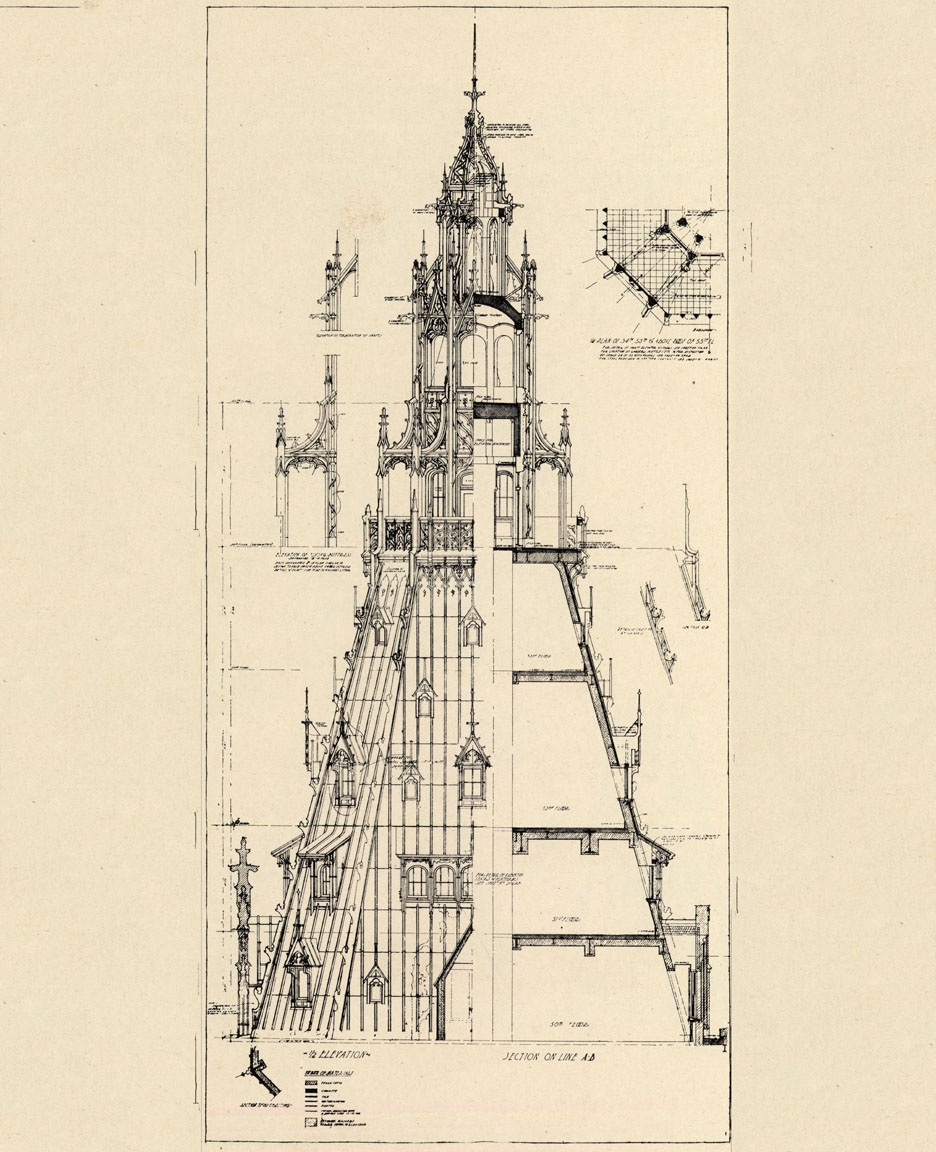

WOOLWORTH SPIRE

Woolworth Spire, Elevation and Section, reproduced from American Architect, March 26, 1913. Collection of The Skyscraper Museum, Gift of Andrew Alpern.

The Woolworth Building project specifications called for handcrafted and costly "foliate or intricate ornamental parts." The Façade was clad in glazed terra-cotta, molded into gothic crockets, pinnacles, and gargoyles. The roof was covered in copper sheets and ribs that patinated to a soft green color and crowned with lacey copper tracery. An example of which from a lower floor of the building hangs on our gallery's west wall. The delicate drawing from the Cass Glibert office at the left illustrates the extraordinary attention to details that characterized the design, even almost 800 feet above the sidewalk.

Like the World Building and others before it, the Woolworth Building featured a public observation deck that offered tourists the chance to combine "the thrill of extreme height coupled with the sensational geography of distance," as the architectural historian Gail Fenske has written.

By 1916, the pinnacle observatory drew more than 100,000 people a year from over sixty countries. To reach the top, sightseers purchased tickets for 50 cents (around $11 today) at a booth near the Barclay Street entrance, then shuttled in a high-speed elevator to the 54th floor, where they could buy postcards, souvenirs, and ice cream at the "highest retail location in the world." To ascend to the 58th-floor outdoor terrace, they could take a six-person circular glass elevator or climb a spiral stair.

From this aerie, the city lay below in a thrilling panorama. As described in the illustrated souvenir guidebook Above the Clouds and Old New York (1913) by H. Addington Bruce:

Looking down on the thousands of great structures, the wonderful bridges that span the East River, the beautiful parks, the great steamers berthed at piers along the rivers, one realizes the grandeur and vastness of the metropolis. The serried peaks made by the giant buildings, towers, church steeples all seem to contend with each other for the distinction of "highest and greatest." But above them all rises the Woolworth Building, calm and unassailable.Today, the tower floors pictured here are being transformed into a single seven-story penthouse apartment priced at more than $100-million.