The Skyscraper Museum is devoted to the study of high-rise building, past, present, and future. The Museum explores tall buildings as objects of design, products of technology, sites of construction, investments in real estate, and places of work and residence. This site will look better in a browser that supports web standards, but it is accessible to any browser or Internet device.

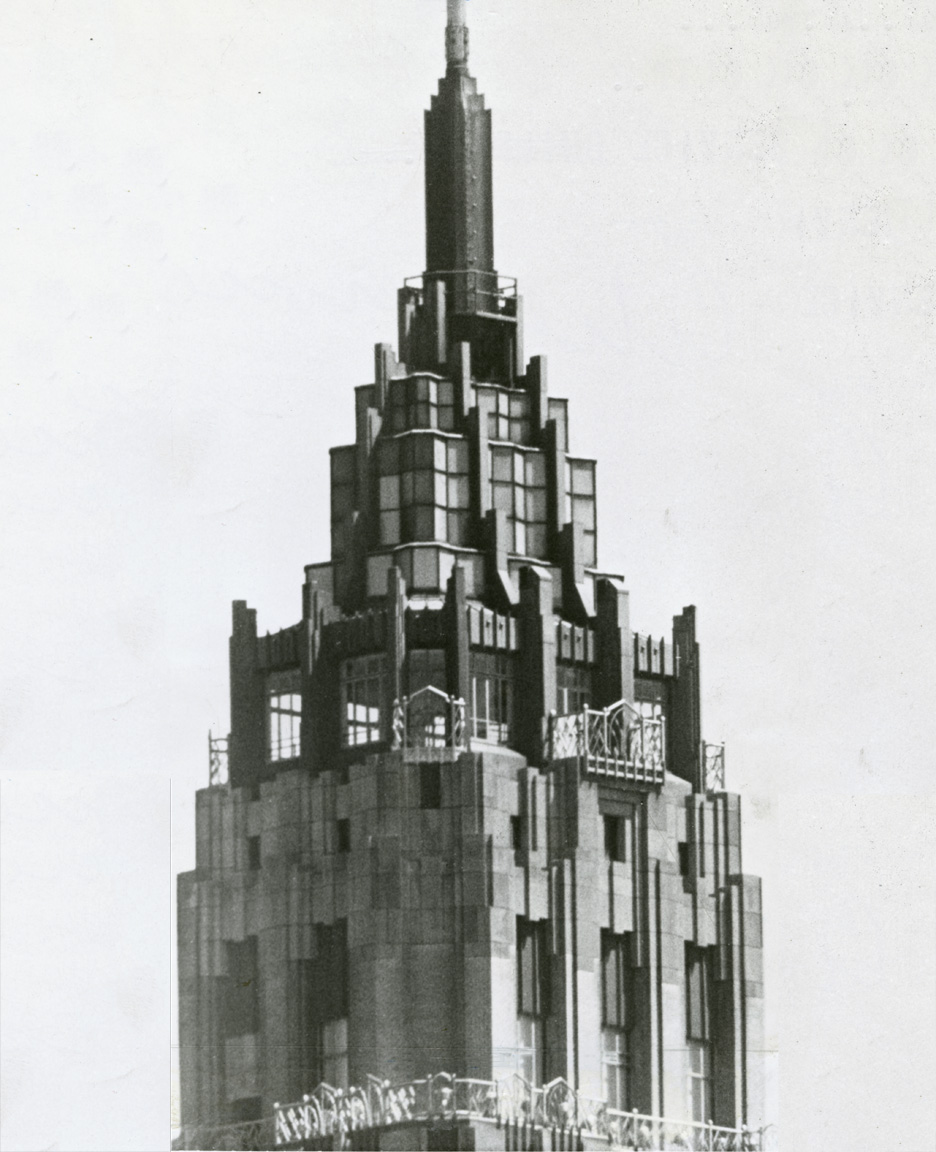

CITIES SERVICE BUILDING

Cities Service Building / World Telegram & Sun photo by Walter Albertin, August 8, 1961, Library of Congress.

The Wall Street area’s most spectacular observation gallery crowns the former Cities Service Building at 70 Pine Street. On the 66th floor, a glass-enclosed room only 23 x 33 feet with six outdoor balconies, created a solarium-like space by day and a glowing crystal jewel by night. Originally planned as the private “watch tower” for the penthouse apartment of Cities Service founder, Henry L. Doherty, in 1932 the upper floors instead became corporate offices and an observation gallery opened to the public. It could be visited from 10am to 6pm at a price of fifty cents, and a quarter for Cities Service employees and building tenants.

At its opening, the observation gallery received considerable publicity for its healthful upper-level air and sun. “It does pep you up,” attendant Martha Midboe told the Evening Post. A visiting bond seller told another reporter that he enjoyed the room “above the sordid chitchat of the Street” and the lofty view “where I can watch my ship come in.”

Architectural historian Daniel Abramson described the appeal of visiting the Cities Service Building’s living room-like observation gallery and the benefits of the clear air on its terrace overlooks and the 360-degree view across rivers, harbors, and mountains see from its expansive windows. “At this height, in the eerie skytop quiet, the city loses its human definition, becomes abstracted and itself seemingly naturalized.” The European modernist architect Le Corbusier remarked about a similar nighttime view from another skyscraper vantage, “No one can imagine it who has not seen it. It is a titanic mineral display, a prismatic stratification shot through with an infinite number of lights, from top to bottom, in depth, in a violent silhouette like a fever chart beside a sick bed. A diamond, incalculable diamonds.”

Today, the top three floors of the building are being converted into a restaurant and lounge as part of an apartment and hotel conversion project led by Rose Associates.

CITIES SERVICE OBSERVATION GALLERY

Cities Service Observation Gallery

Room, from Edwin C. Hill, 60 Wall Tower (1932)

Collection of

The Skyscraper Museum.

In his book Skyscraper Rivals: The AIG Building and the Architecture of Wall Street, the architectural historian Daniel Abramson described details of the modernist design and the elite and invigorating experience of a visit to the glass-enclosed gallery atop the Cities Service Building:

Visitors ascended into Doherty’s “watch tower” observation gallery either up narrow stairs on the north side or by an adjacent small elevator running from the 60th floor. The metal-clad cab rose through the observation gallery floor—then amazingly descended back beneath hinged hatches. The observation gallery’s deck now lay completely unobstructed in every direction through continuous banks of windows from knee level up, and around the chamfered glass corners. Across the terrazzo floor lay sleek modern tubular steel furniture. Phones plugged into the floor. At the center a compass pointed out the cardinal directions and enclosed the Cities Service emblem. Glass doors at the corners and north and south sides led out onto six small slate terraces, enclosed only by chest-high aluminum railings, that felt like crow’s nests pitched out into the harbor air. Below was the city. South across New York harbor lay Staten Island and the New Jersey coast. West across the Hudson shimmered New Jersey’s inland mountains. To the north appeared glimpses of Westchester County and to the east, Babylon and Huntington on Long Island.

Continuing, he evokes the romance of the views in language that resembles the language of literature of the Twenties:

Architecture dwindles to its starkest essence: a cloud-capped primitive hut. The corners dissolve, walls are reduced to thin piers, the roof to nearly nothing. From the terraces one can hardly see the supporting skyscraper below. In the small space, with the elevator sunk in the floor, one can imagine being all alone, as Doherty must have dreamed, magically levitated, master in vision of the metropolis’ great sweep, standing at the center of the marble compass on the pivot of the universe. The bracing bodily experience intensifies physical self-awareness, as if one has ascended a man-made mountain in transcendence of the reality below.