The Skyscraper Museum is devoted to the study of high-rise building, past, present, and future. The Museum explores tall buildings as objects of design, products of technology, sites of construction, investments in real estate, and places of work and residence. This site will look better in a browser that supports web standards, but it is accessible to any browser or Internet device.

JOHN HANCOCK CENTER

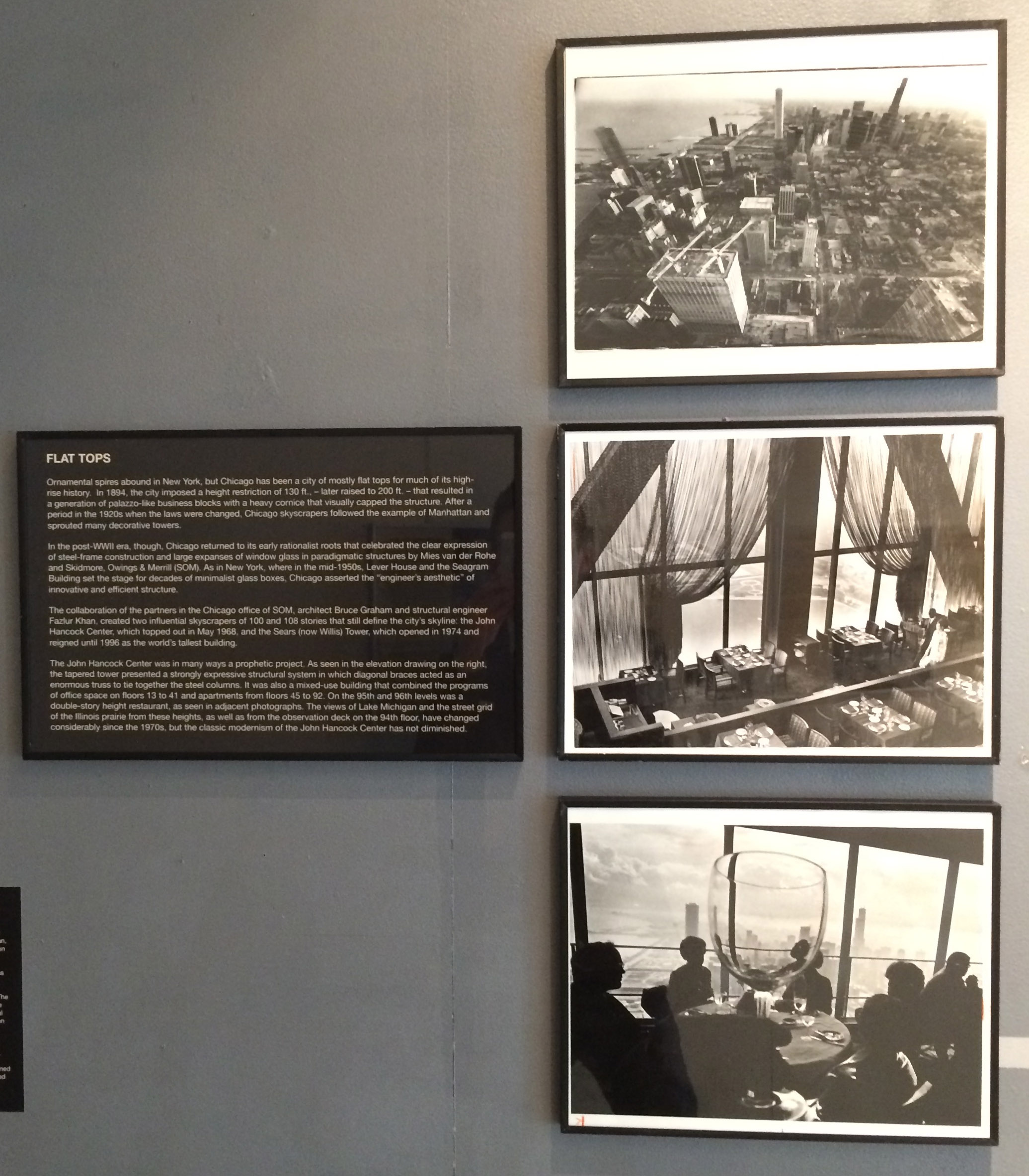

View looking southward from John Hancock Observation Deck, showing North Michigan Avenue skyline and Water Tower Place under construction in foreground. Daily News, March 14, 1975, Photograph by M. Leon Lopez, from the Collection of The Skyscraper Museum .

Ornamental spires abound in New York, but Chicago has been a city of mostly flat tops for much of its high-rise history. In 1894, the city imposed a height restriction of 130 ft., – later raised to 200 ft. – that resulted in a generation of palazzo-like business blocks with a heavy cornice that visually capped the structure. After a period in the 1920s when the laws were changed, Chicago skyscrapers followed the example of Manhattan and sprouted many decorative towers.

In the post-WWII era, though, Chicago returned to its early rationalist roots that celebrated the clear expression of steel-frame construction and large expanses of window glass in paradigmatic structures by Mies van der Rohe and Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM). As in New York, where in the mid-1950s, Lever House and the Seagram Building set the stage for decades of minimalist glass boxes, Chicago asserted the “engineer’s aesthetic” of innovative and efficient structure.

The collaboration of the partners in the Chicago office of SOM, architect Bruce Graham and structural engineer Fazlur Khan, created two influential skyscrapers of 100 and 108 stories that still define the city’s skyline: the John Hancock Center, which topped out in May 1968, and the Sears (now Willis) Tower, which opened in 1974 and reigned until 1996 as the world’s tallest building.

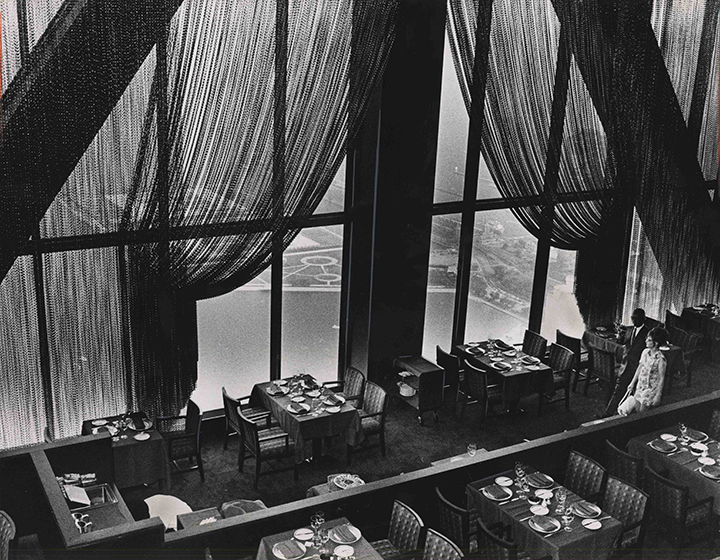

The view from the 95th floor restaurant in the John Hancock Building is through or around a draped curtain of chains to the east. Daily News, August 15, 1970, from the Collection of The Skyscraper Museum

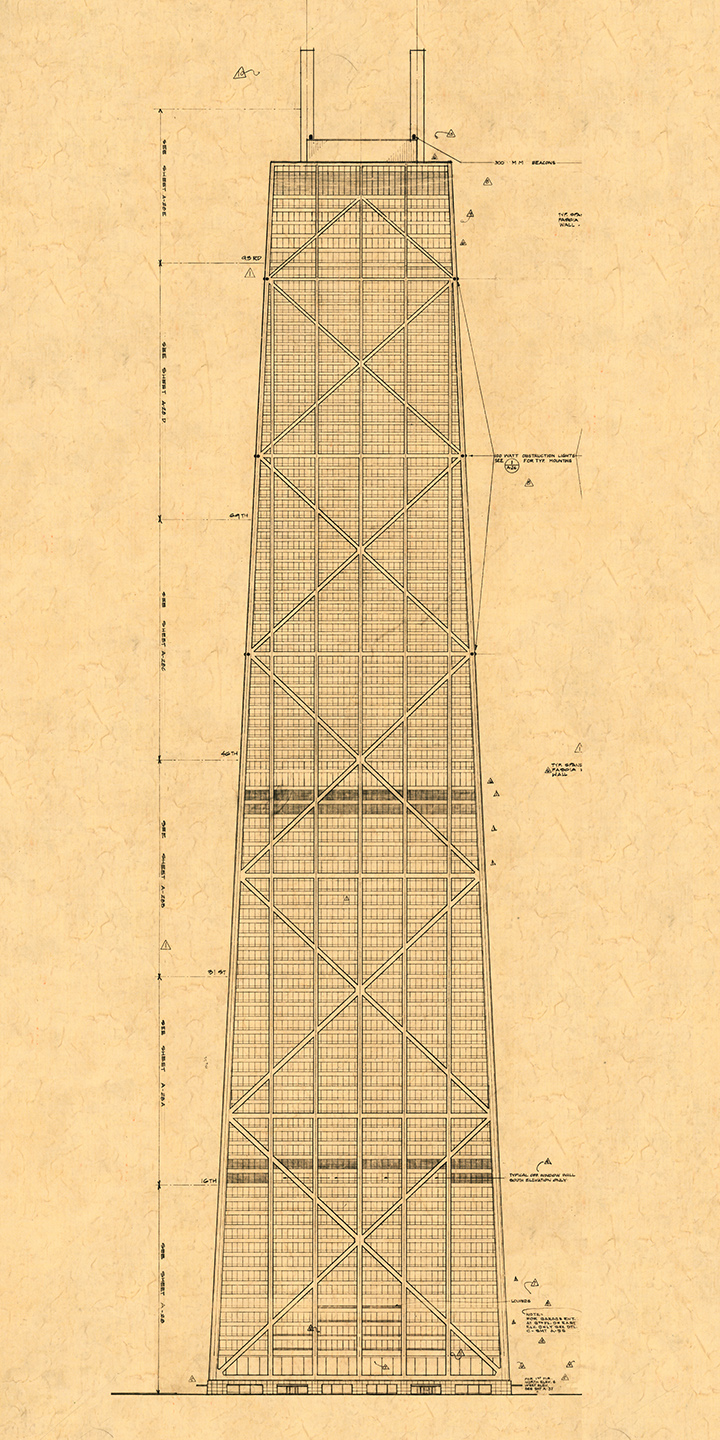

The John Hancock Center was in many ways a prophetic project. As seen in the elevation drawing below, the tapered tower presented a strongly expressive structural system in which diagonal braces acted as an enormous truss to tie together the steel columns. It was also a mixed-use building that combined the programs of office space on floors 13 to 41 and apartments from floors 45 to 92. On the 95th and 96th levels was a double-story height restaurant, as seen in the above photographs. The views of Lake Michigan and the street grid of the Illinois prairie from these heights, as well as from the observation deck on the 94th floor, have changed considerably since the 1970s, but the classic modernism of the John Hancock Center has not diminished.

Blueprint elevation of the John Hancock Center

Courtesy of SOM