The Skyscraper Museum is devoted to the study of high-rise building, past, present, and future. The Museum explores tall buildings as objects of design, products of technology, sites of construction, investments in real estate, and places of work and residence. This site will look better in a browser that supports web standards, but it is accessible to any browser or Internet device.

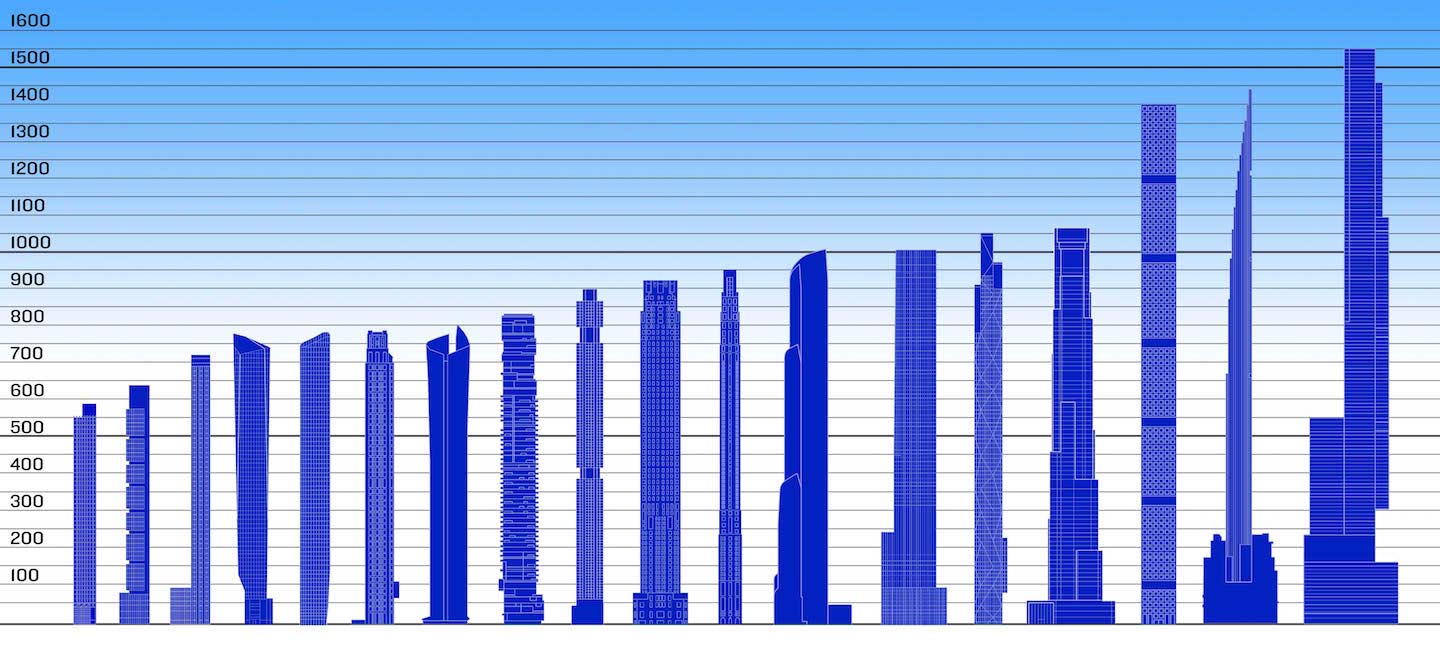

NEW YORK'S SUPER-SLENDERS Click to enlarge and hover for IDs

(October, 2016)

A new form in skyscraper history has evolved in New York over the past decade: the super-slim, ultra-luxury residential tower. These pencil-thin periscopes — all 50 to 90+ stories — use a development and design strategy of slenderness to pile their city-regulated maximum square feet of floor area (FAR) as high in the sky as possible to create luxury apartments defined by spectacular views. The basic, yet complex principles of the economics, engineering, and design of this new type of super-slender towers were detailed in The Skyscraper Museum’s 2013/14 exhibition SKY HIGH & the Logic of Luxury, which is archived in full text and images here.

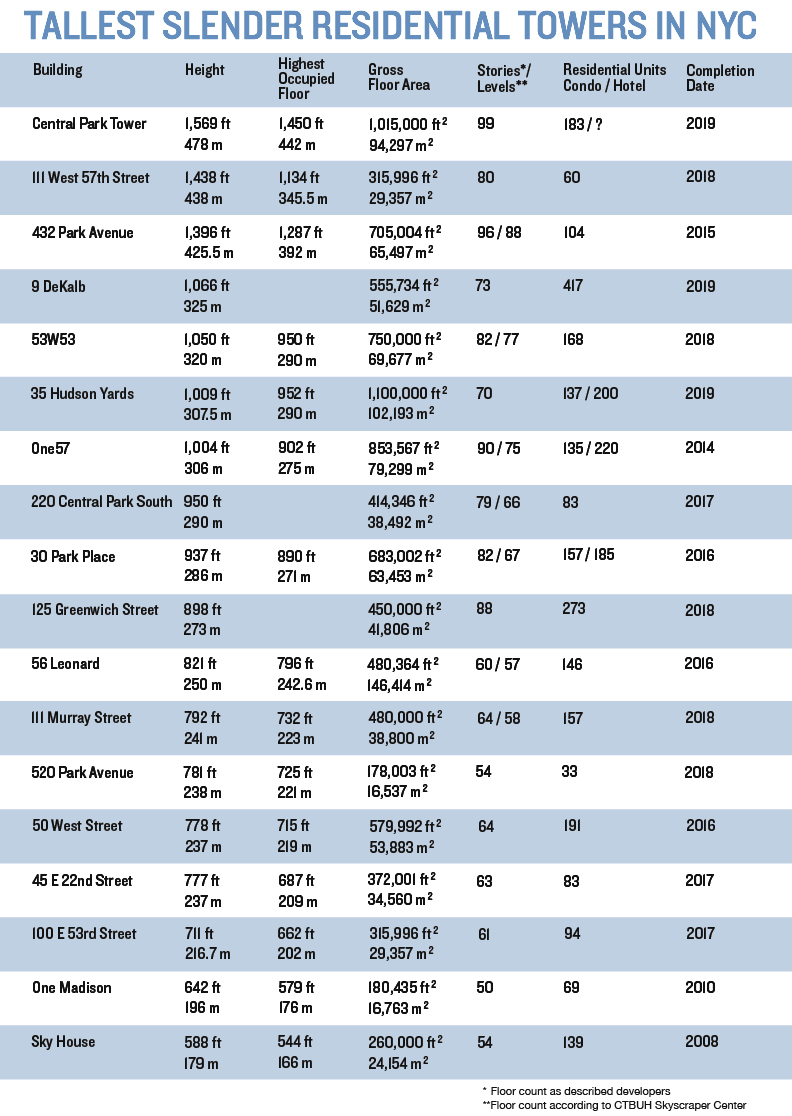

This new chart and the grid of images below updates the exhibition’s list and includes 18 slender towers that in May 2016 were either completed or in early stages of construction. The defining characteristic of these new towers is not height, but slenderness. Slenderness is a proportion based on the width of the base to the height of the building. A tower can be very tall, but not slender, and it can be slender without being very tall.

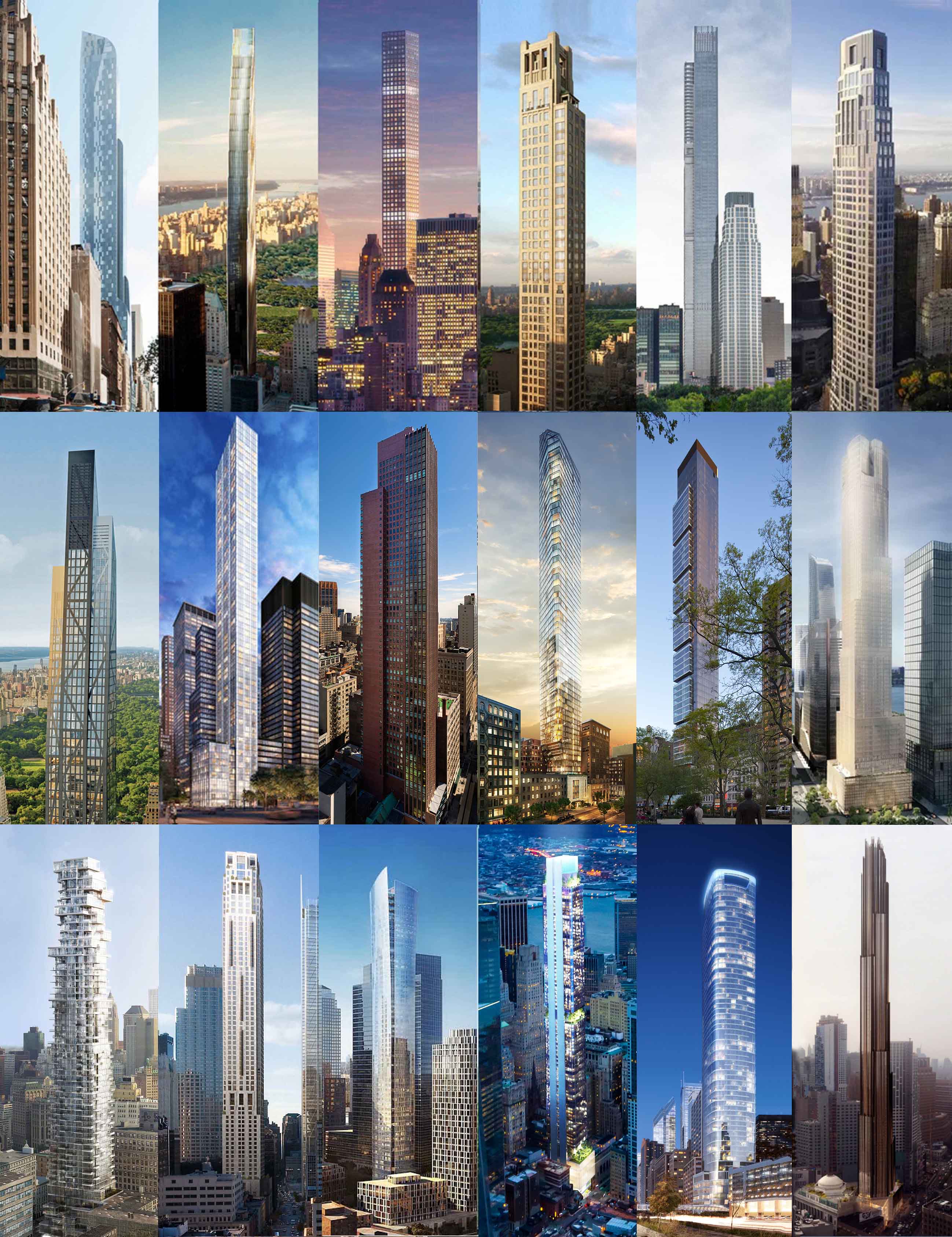

Top: One57, 111 West 57th Street, 432 Park Avenue, 520 Park Avenue, Central Park Tower, 220 Central Park South. Middle: 53W53rd, 100 E 53rd Street, Sky House, 45 E 22nd Street, One Madison, 35 Hudson Yards. Bottom: 56 Leonard, 30 Park Place, 111 Murray Street, 125 Greenwich Street, 50 West Street, 9 DeKalb Ave.

Top: One57, 111 West 57th Street, 432 Park Avenue, 520 Park Avenue, Central Park Tower, 220 Central Park South. Middle: 53W53rd, 100 E 53rd Street, Sky House, 45 E 22nd Street, One Madison, 35 Hudson Yards. Bottom: 56 Leonard, 30 Park Place, 111 Murray Street, 125 Greenwich Street, 50 West Street, 9 DeKalb Ave.

Both prime neighborhoods and great views have added value in New York. Many developers say that apartment buyers shop first for neighborhood, then views, then amenities. But in the new crop of super-slender towers, the value of views is clearly the driving force for the tower form. Central Park is the gold standard, but other geographies also have great appeal if they can command climb to 600 to 800 feet or taller and command sweeping panoramas of the city.

The renderings of the 18 slender towers are organized loosely by neighborhood. The top row groups the best-known buildings near the southern end of Central Park and especially on the posh cross-town commercial 57th Street, nicknamed “Billionaires’ Row.” The middle row, which include four projects initiated before the 2008 banking crisis and recession, are located in central midtown and midtown south near Madison Square, as well as 35 Hudson Yards, which in recent renderings is marginally slender. The bottom row, of which three are topped out and completely clad are all in lower Manhattan, south of Chambers Street, with the exception of the last building, which will become the tallest building in Brooklyn.

Designed by thirteen different architectural firms in a wide range of styles from historical to avant-garde and clad in materials from limestone to all-glass curtain walls, the rendering of these towers underscore that the slenderness development strategy is the unifying characteristic of the new typology.

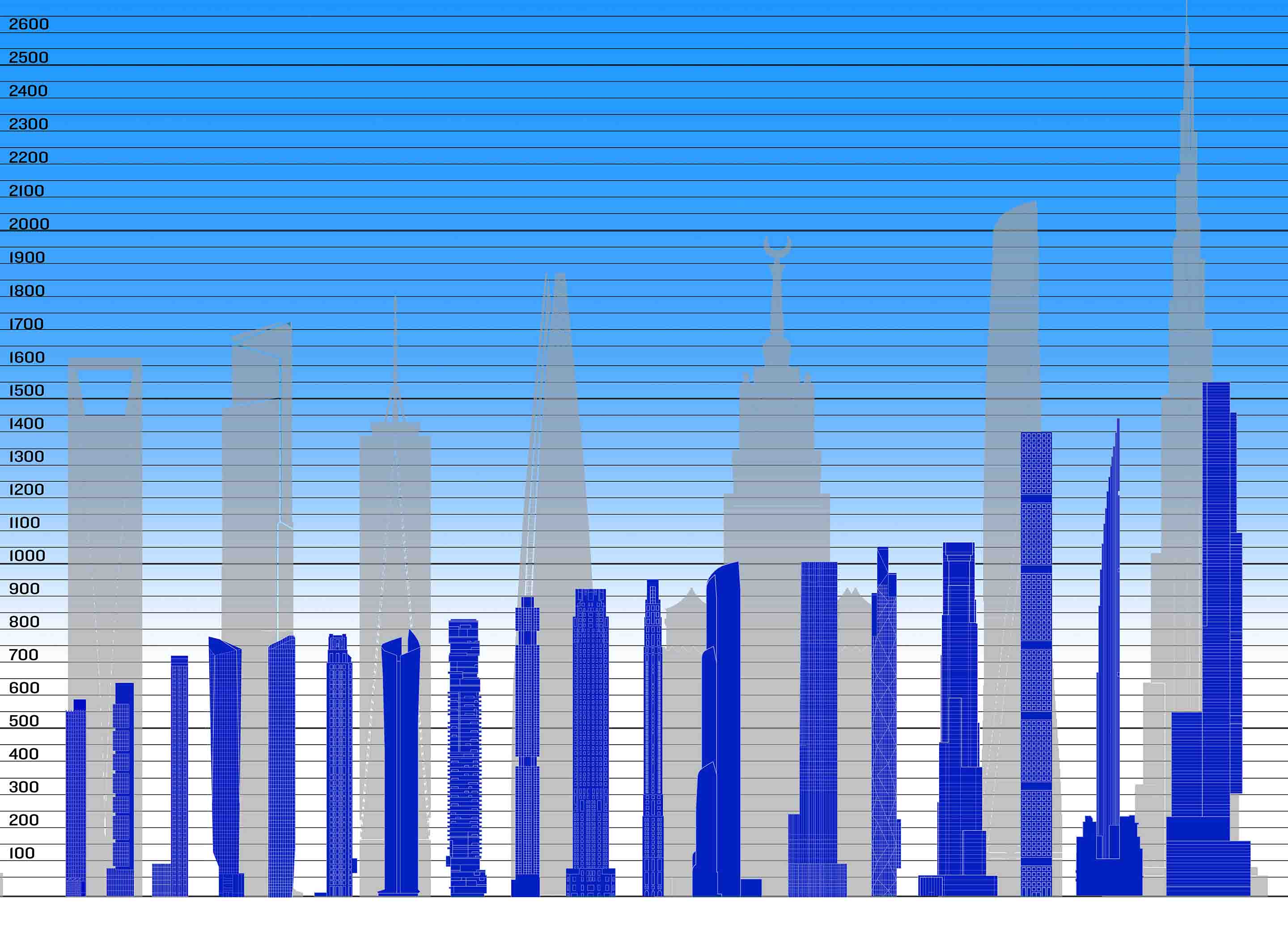

PUTTING THINGS IN PROPORTION

Tall and BIG are not the same thing. This chart places behind the line up of New York's slender towers the silhouettes, to scale, of several of the world's tallest and largest skyscrapers, all of which include residences or hotel spaces, except for New York's One WTC. From left to right they are: Shanghai World Financial Center, CTF Finance Centre, One WTC, Lotte World Tower, Mecca Royal Clock Tower, Shanghai Tower, Burj Khalifa. The smallest total floor area (GFA) in any of these skyscrapers is Lotte World Tower with 304,081 m² / 3,273,101 ft² of GFA.

WHAT IS SLENDERNESS?

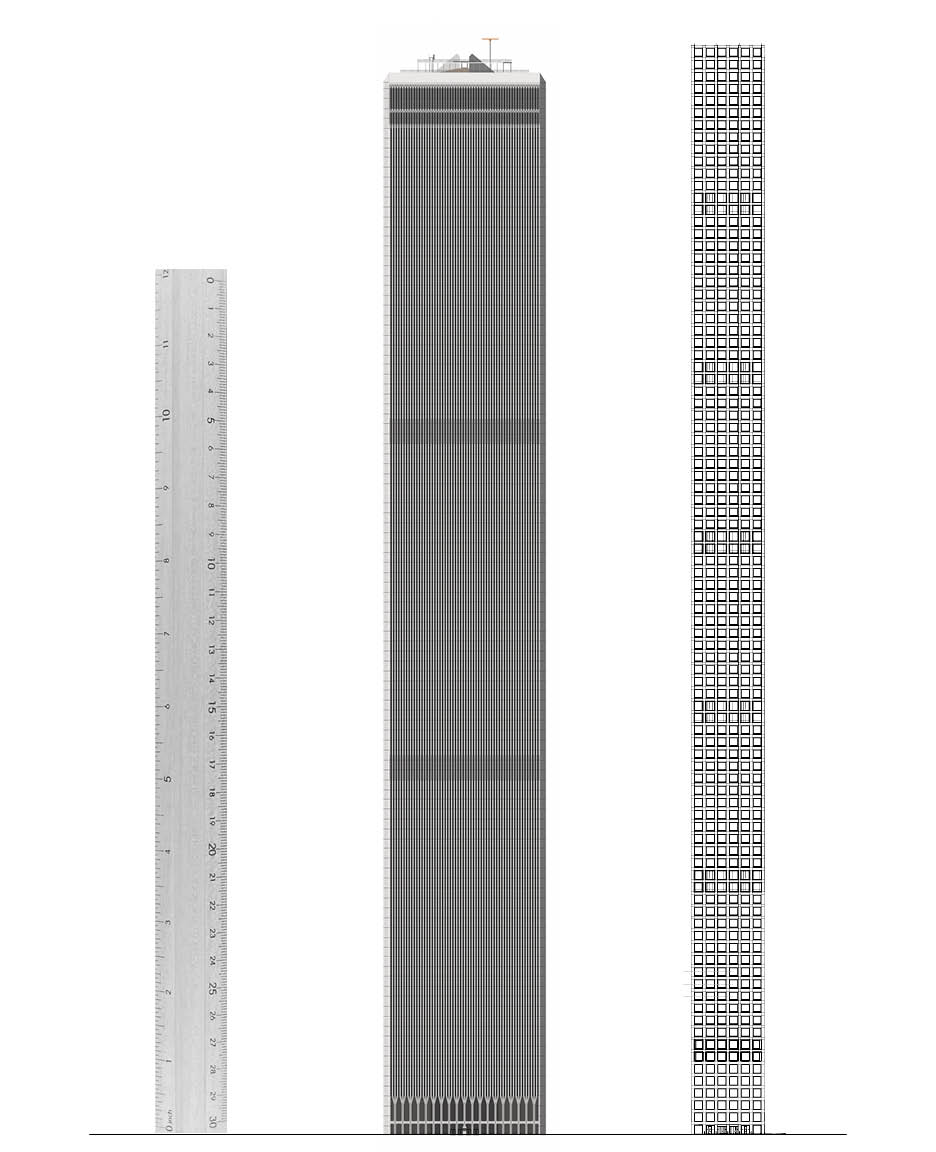

Image credit: The Skyscraper Museum

"Slenderness" is an engineering definition. Structural engineers generally consider skyscrapers with a minimum 1:10 or 1:12 ratio (of the width of the building's base to its height) to be "slender." Slenderness is a proportion based on the width of the base to the height of the building.

The World Trade Center North Tower was the tallest building in the world on its completion in 1971. But at a height of 1,368 feet and with a big square floor plate, 209 feet on each side, the ratio of its base to height was less than 1:7. This image compares at the same scale the former 1 WTC and the residential tower 432 Park Avenue, now under construction. The base of the apartment building is 93 feet square, and the shaft will rise to 1,396 feet, making its slenderness ratio 1:15. To visualize a 1:12 ratio, we show a ruler 1-inch wide and set on end. The eighteen towers on our chart range from a ratio of 1:10 to an extraordinary 1:23 at 111 W. 57 Street.

HOW TALL? HOW BIG?

Lining up the super-slenders by ascending height does not correlate to arranging them by their size in gross floor area (GFA). An extreme example is the difference in floor area of two tallest towers on the chart: Central Park Tower will comprise slightly more than 1 million sq. ft., while 111 West 57th Street will contain less than a third of that total. There is a more than five-fold range of size among the super-slenders: the two towers with the smallest floor areas– less than 200,000 sq. ft. – are 520 Park Avenue and One Madison.

Click to expand the chart

Below, the Museum's line-up of buildings in the chart above are detailed, starting from Sky House (completed in 2008), which is the both earliest and the shortest of the slender tower type and ending with the tallest, Central Park Tower (in May 2016 in the early stages of construction), which is reported will rise to 1,569 feet. For a history of slenderness, the influence of zoning, and role of air rights click here.

18. Sky House

Height to Tip: 588 ft / 179

Highest Occupied: 544 ft / 166 m

Stories / Levels: 54

Completed: 2008

One of the loveliest buildings of the post-2001-pre-2008 moment of slenderness is SKY HOUSE, a 55-story slab rising on a lot just 45 ft. wide on 29th St and running through the block to 30th St, midblock between Fifth and Madison Ave. Having purchased air rights from the landmarked red brick "Little Church Around the Corner," the developers, architects FXFOWLE, and engineers WSP Cantor Seinuk created a contextual design that emphasized verticality in the close set, brick-faced structural columns. Their exploration of the design process is described in the video from a presentation for the skyscraper on February 19, 2009.

See Sky House in SKY HIGH17. One Madison

Height to Tip: 642 ft / 196 m

Highest Occupied: 579 ft / 176 m

Stories / Levels: 50

Expected completion: 2010

One Madison was largely completed in 2009, but the project hit the market at the beginning of the recession, and the first developers had to declare bankruptcy and sell the building.

The tower's modular form is delineated by seven volumetric pods, constructed from clear white and green glass. These cube-like forms deconstruct the building's mass and give it a sense of lightness. Unlike typical residential and commercial buildings, this modular concept creates varied units and a combination of effects allowing for a unique and expressive building form. Floor-to-ceiling glass walls draw the eye outwards to the city, creating a dramatic and picturesque backdrop that changes with the seasons. Cantilevered from the main shaft, the pods lend functionality beyond their aesthetic appeal, extending the tower's 2,700 square-foot floor plate to 3,300 square-feet and modulating the building form. This unique feature grew out of the need to expedite construction on the main tower and from the desire to offer a mix of apartment types, some with terraces.

Residences range from 805 square-foot studios to a 7,143 square-foot triplex penthouse, and the property features luxurious amenities, including a spa, swimming pool, fitness center, media/screening room, children's room, and outdoor terrace park. To create a serene and intimate entry, residents enter the building on 22nd Street, a configuration that also allows for a ground floor commercial space to complement the existing retail activity of 23rd Street

See One Madison in SKY HIGH16. 100 East 53rd Street

Height to Tip: 711 ft / 216 m

Highest Occupied: 662 ft / 202 m

Stories / Levels: 61

Expected completion: 2017

The challenge of designing a tower on the same block as Mies van der Rohe’s modernist masterpiece, the Seagram Building, was given to British architect Sir Norman Foster by developers Aby Rosen and Michael Fuchs of RFR Realty in 2005. The owners of both 100 East 53rd Street and the landmark Seagram Building, Rosen and Fuchs needed approval from the Landmarks Preservation Commission and local community boards to begin construction on the tower, which alludes to its mid-century neighbors with a glass façade, exposed mullions, and a minimal, geometric form, while greatly exceeding it in terms of height and slenderness.

To attain the building’s 711-foot height, Rosen and Fuchs first merged the adjacent lots of the two towers, allowing for the transfer of 200,965 square feet of unused air rights from Seagram Building, which occupies only 52 percent of its site, to 100 East 53rd Street. In return, RFR Realty came to an agreement with the New York Landmarks Conservancy that requires the developers to permanently maintain the bronze and glass exterior of the modernist icon. Architectural historian Phyllis Lambert and New York City’s Landmarks Preservation Commission also voiced concerns that 100 E 53rd, rising 200 feet feet above the Seagram Building, would detract from the visual impact of the landmark skyscraper as seen from Park Avenue. However, the new tower is set back 150 feet from the slab of the Seagram Building, allowing it to remain virtually invisible from the street below.

The site for 100 East 53rd Street was purchased in 2005 by RFR, along with China Vanke and Hines, for $31.5 million with a vision to replace the 36-story Y.M.C.A. building that then occupied the location with a luxury hotel-condominium tower. In 2007, Hong Kong-based Shangri-La Hotels & Resorts signed on to create a hotel on the bottom portion of the building but soon pulled from the project amidst the financial crisis of 2008. Moving forward with a largely residential building, 100 East 53rd Street contains 25,000 square feet of retail, a range of luxurious amenities, and condominiums from the fifth to sixty-first floor. Prices for the 94 units were revealed to range from $3.3 million for a single bedroom to $55 million for a penthouse duplex.

15. 45 East 22nd Street

Height to Tip: 777 ft / 237 m

Highest Occupied: 687 ft / 209 m

Stories / Levels: 63

Expected completion: 2017

With no more than two apartments per floor, 45 East 22nd Street will feature full floor residences from the 55th floor up. Capping off at a height of 777 feet, the building will be the tallest in the Flatiron District, 135 feet taller than the nearby One Madison. Developed by Bruce Eichner with architects Kohn Pedersen Fox, the tower’s floor plans expand as it rises - swelling from 75 feet wide at its base to 125 feet at the top - allowing for a more floor area for the most expensive units in the buildings highest stories, and culminating in a 7,000 square foot duplex penthouse on the 64th and 65th floors.

Eichner began developing the project in 2010 after an unsuccessful bid to purchase One Madison and soon started compiling air rights from numerous neighboring buildings. KPF was chosen to design the project, owing in large part to their cantilevered proposal, which took advantage of the building's small site by eventually reaching out 17 feet above a neighboring low-rise. At street level, the tower’s facade shifts from glass to a rusticated, five-story granite base to relate to its historical context.

The tower contains a diverse offering of residential units, ranging in price from $2.5 million to $40 million for the largest penthouse, and is expected to pull in $714.6 million in total sales.

14. 50 West Street

Height to Tip: 778 ft / 237 m

Highest Occupied: 715 ft / 219 m

Stories / Levels: 64

Expected completion: 2016

Having topped out in September of 2015, 50 West Street is on target for completion this year, with occupancy scheduled for this fall. The 778 foot, 64 floor Helmut Jahn-designed tower will feature a private observation deck on the top floor reserved exclusively for residents. Located blocks away from the World Trade Center and the Financial District, the slender skyscraper will offer views of New York Harbor and the Statue of Liberty through its curvilinear, all-glass facade. With this curved glass design, corner panels and vertical mullions are unnecessary, giving residents a completely unobstructed view. On the south side of the tower, the facade sweeps over the curved cantilevered base to a pedestrian walkway between the building and the Battery Garage, using the dramatic curves to open up a formerly claustrophobic space.

Aside from the observation terrace, the building features a plethora of luxurious amenities, including a “water club,” full-floor fitness center, entertainment floor, and, on the third floor, fifteen “commercial condominiums,” or private offices, that vary in size from 280 to 830 square feet and are available for purchase by the tower’s residents. 50 West contains 191 condos with interiors designed by Thomas Juul-Hansen, ranging from one- and four-bedroom units to full- and half-floor penthouses with an average price of $2,400 per square foot. Two of the building's penthouses are currently on the market for $20.3 million and $24.5 million.

See 50 West Street in SKY HIGH13. 520 Park Avenue

Height to Tip: 781 ft / 238 m

Highest Occupied: 725 ft / 221 m

Stories / Levels: 54

Expected completion: 2018

Following the incredible success of 15 Central Park West, developers Arthur and William Lie Zeckendorf again called on architect Robert A.M. Stern to design a limestone-clad tower. Entered on the crosstown E. 60th St., between Park and Madison Avenues, 520 Park will rise 54 stories, but contain just 33 residential units. The Zeckendorfs, along with Park Sixty LLC and Global Holdings Inc., purchased the 6,025 square foot lot in 2013 for $8 million and soon demolished the existing low-rise buildings. To give the tower its high-profile Park Avenue address, the developers purchased the transferable development rights from the landmarked neighboring Christ Church and Grolier Club for more than $30 million for the air rights above the church and adjacent Grolier Club. In March, 2014, the deal was reported to set a new record of $430 per square foot for 70,659 square feet of air rights, which allows the mid-block building to reach its projected 781-foot height.

Like other RAMSA towers, 520 Park Avenue evokes the form and texture of New York’s historic pre-war skyscrapers. Amenities include a salon, garden, health club and pool, as well as storage units and wine cellars with prices ranging from $125,000 to $275,000. Condominiums start at $16.2 million for 4,613 square foot, four bedroom, 5.5 bathroom, full-floor units on the 14th through 20th floors. The top floor triplex, available for $130 million with $51,000 in monthly fees and taxes, is 12,400 square feet with an addition 1,250 square feet of outdoor terraces.

12. 111 Murray Street

Height to Tip: 792 ft / 241 m

Highest Occupied: 732 ft / 223 m

Stories / Levels: 58

Expected completion: 2018

While not the tallest residential tower in downtown Manhattan, 111 Murray Street, developed by Fisher Borthers and Witkoff Group with architects Kohn Pedersen Fox, David Rockwell, and MR Architecture & Decór, will make a mark on the skyline with its distinctive flared glass top. Inspired by the form of Murano glass vases, the building’s glass facade expands outwards from the 40th floor to the 58th floor, reaching a height of 792 feet to offer unimpeded views of the Hudson River.

Located two blocks north of One World Trade on the edge of TriBeCa, 111 Murray Street will be built on 31,000 square foot lot, formerly the site of St. John University, that Fisher Brothers and Witkoff purchased for $223 million in 2013. The building will contain 157 luxury apartments, as well as a double-height lobby, tearoom, patisserie, private garden, dinning area, sculpture garden, Turkish bath, lap pool, and 10,000 square foot public plaza. The inclusion of a public plaza, designed by Hollander Design Landscape Architects, allowed the developers to build 20 percent larger than the site allows for, attaining an FAR of 12 instead of 10.

71 of the building’s units are full-floor, with elevators opening directly into the apartments. Prices start at $2 million for a one-bedroom and $17.5 million for a five-bedroom, though the costs for the most luxurious penthouses have yet to be revealed.

11. 56 Leonard

Height to Tip: : 821 ft / 250 m

Highest Occupied: 796 / 243 m

Stories / Levels: 60 / 57

Expected completion: 2016

Designed by the Pritzker Prize-winning Swiss firm Herzog & de Meuron, the tower at 56 Leonard stands apart from other slender towers. Its downtown location at the edge of chic Tribeca, a largely residential neighborhood in an area of converted late-19th century commercial structures, allows it to rise high above surrounding rooftops. Sited just outside the landmark district, and using air rights purchased from the adjacent New York Law School, the tower stretches to nearly 800 feet and 57 stories.

The unusual staggered silhouette, especially of the upper floors, that earned the nickname "the Jenga building" after the game of stacking and balancing wood blocks, also sets the form apart. Herzog & de Meuron evoke a Modernist metaphor of "villas in the sky" by vertically stacking glass-house unit upon unit. The effect is most dramatic on the top eleven stories, where the floor slabs cantilever as much as 25 feet and floor-to-ceiling glass and outdoor balconies create a sense of endless space. Below these penthouses, though, there is still insistent variety: the developer claims that each of the 145 units has a unique floor plan, which required innovative structural engineering approaches. According to the building's engineers WSP Cantor Seinuk, the structure of stacked, cast-in-place concrete flat plate floors is supported by reinforced concrete columns and shear walls. The central concrete core is supplemented by two sets of outrigger walls and a belt wall connecting the exterior columns to the building's core. The shear walls and columns employ high strength concrete of 12,000 psi at lower levels, reduced to 7,000 psi at higher levels.

Conceived and marketed by the developers as individual artworks, rather than as regular apartments, the condos of 56 Leonard have enjoyed successful sales ever since the project, first designed before the recession of 2008, began construction in 2012. The cache and high value of the Tribeca neighborhood and the developer's commitment to high-profile designers, including commissioned sidewalk piece by the artist Anish Kapoor, has produced unusually high prices for downtown real estate, including a penthouse in contract for a reported $47 million.

See 56 Leonard in SKY HIGH10. 125 Greenwich Street

Height to Tip: 898 ft / 273 m

Highest Occupied:

Stories / Levels: 88

Expected completion: 2018

Set to be Lower Manhattan’s tallest new residential tower, at 898 feet, the Rafael Vinoly-design 125 Greenwich Street will reach 88 stories, though official figures and renderings have yet to be released. Located in the midst of the Financial District on a 9,000 square foot lot nearby the World Trade Center site, the pencil-thin tower is being developed by SHVO, Bizzi & Partners Development, and New Valley.

While earlier images of the project showed a 1,350-foot, all-glass, rectangular extrusion, the latest unofficial renderings depict a series of three glass prisms, separated by landscaped terraces, anchored to a concrete spine, and topped off with a rectilinear spire. At street-level, the 450,000 square foot building will offer retail space to the World Trade Center corridor.

9. 30 Park Place

Height to Tip: : 937 ft / 286 m

Highest Occupied: 890 ft / 271 m

Stories / Levels: 82 / 67

Expected completion: 2016

Using slenderness as a strategy to lift its residences high in the sky, 30 Park Place, designed by Robert A.M. Stern Associates, pulls as far away as possible from the Woolworth Building — once the world's tallest — with which it occupies the same block and now overtops. A courtyard separating the two enables 30 Park Place to achieve its height while allowing Woolworth to remain as a free-standing structure.

As with the earlier design for 15 Central Park West, Robert A. M. Stern Associates employs a classical vocabulary of masonry walls and picture windows to refer to the traditions of historic architecture, in counterpoint to both the all-glass office towers of the World Trade Center, both planned and currently under construction, and to the Gothic spire of the Woolworth Building. In its height and slenderness, 30 Park Place relates to the office-building ensemble at Ground Zero, also being developed by Silverstein Properties.

The 937-foot tall, 67-story limestone-clad structure — estimated to be completed in 2016 — is a mixed-use project, with the 185-room The Four Seasons Hotel New York, Downtown on the lower 21 floors. The remainder of the tower, known as the Four Seasons Private Residences New York at 30 Park Place, will comprise 157 luxury condominiums, including full-floor penthouses and setback terraces, with some private residences as large as 6,000 sq. ft..

See 30 Park Place in SKY HIGH8. 220 Central Park South

Height to Tip: 950 ft / 290 m

Highest Occupied:

Stories / Levels: 77 / 66

Expected completion: 2017

Designed by Robert A.M. Stern Architects, 220 Central Park South will rise 950 ft. and contain 83 luxury residential units when it is completed in 2017. The residences will be split between a 17-story villa and the adjacent 66-story tower. 220 Central Park South will stand out from the other towers in the 57th street locale, clad in limestone rather than glass and steel.

Vornado Realty Trust, the project’s developer, participated in a power struggle with Extell, the developer of the nearby Central Park Tower, in the process of acquiring land and permits for 220 Central Park South. Upon hearing about Vornado’s proposed tower, Gary Barnett of Extell reportedly bought the lease on a parking garage that would have to be demolished for Vornado’s project to go forward because the 950-foot tower would block views from his project at 217 West 57th Street. In 2013, the two settled this dispute: Vornado paid Extell $194 million for the parking garage, and both developers agreed to move their projects slightly to secure views.

7. One57

Height to Tip: 1,004 ft / 306 m

Highest Occupied: 902 ft / 275 m

Stories / Levels: 90 / 75

Completed: 2014

At 1,004 ft. tall, One57 was the tallest residential tower in New York City when it was completed in 2014, only to be overtaken by 432 Park (which will in turn only keep its title until the Central Park Tower is completed). One57 is the breakthrough luxury project of the developer Gary Barnett of Extell. Targeted at an ultra-luxury market, One57 combines the program of a hotel and its services and amenities in the lower section and 94 condominium units in the tower. One57 is well-known today for its record-breaking $100 million penthouse sale in January 2015.

Although Barnett had begun to acquire adjacent buildings and air rights as early as 1998, the first design for One57 began in 2005 when the developer commissioned the Pritzker Prize-winning French architect Christian de Portzamparc to prepare design studies for a pair of towers for the two sites one block apart that he owned on W. 57th Street. (The second site is a group of lots that in fall 2013 were in design development by Adrian Smith + Gordon Gill Architecture.) In July 2007, Portzamparc was commissioned to develop the design for the mixed-use, hotel and condominium tower at 157 W. 57 that would rise to 300 meters (c. 1,000 ft.).

The slenderness and massing strategies evolved in dozens of study models in 2008, and the tower reached its definitive form in 2009 in a project the Portzamparc Atelier called "les cascades," referring to the imagery of flowing waterfalls. The curtain wall treatment of varicolored glass panels of blue, gray, and silver reinforced the trope of reflections on water, but Portzamparc also used the term "Klimt effect" to describe the façade, suggesting the mosaic-like decorations of the Viennese modernist painter.

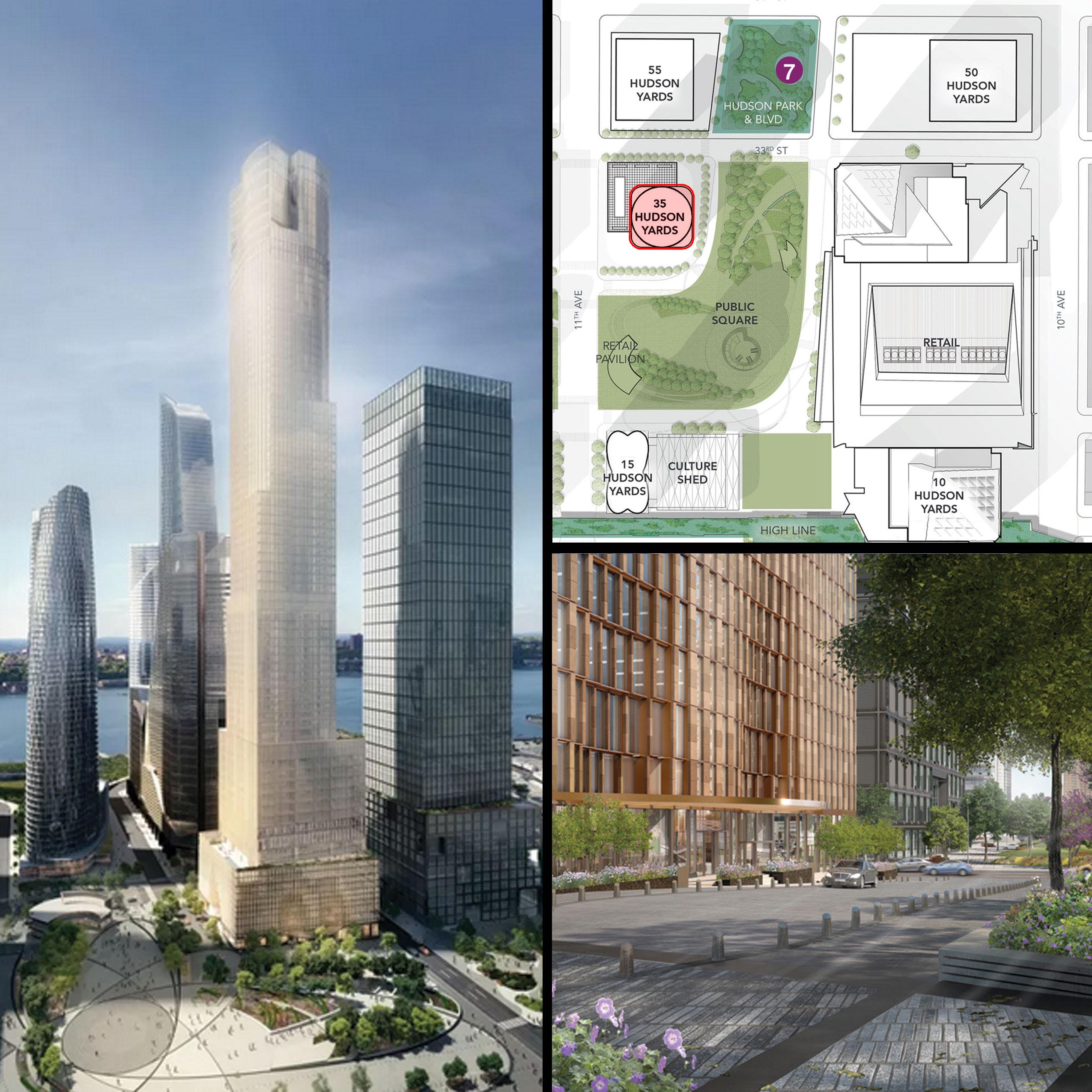

See One57 in SKY HIGH6. 35 Hudson Yards

Height to Tip: 1,009 ft / 308 m

Highest Occupied: 952 ft / 290 m

Stories / Levels: 70

Expected completion: 2019

35 Hudson Yards will be the second residential building constructed in the Hudson Yards megaproject and will feature six floors of office space, 200 hotel rooms, and 137 luxury condominiums. At 70 stories and 1,009 ft., the tower, designed by David Childs with SOM, will be one of the tallest residential buildings in the city and the second tallest of the seven Eastern Yard towers. Like 15 Hudson Yards, the skyscraper has seen design changes, beginning as a 900-foot tower with curvilinear setbacks, then transforming to a cylindrical design. The most recent set of renderings show the building as boxier with setbacks and a curvy top.

5. 53W53 (MoMA Tower)

Height to Tip: 1,050 ft / 320 m

Highest Occupied: 950 ft / 290 m

Stories / Levels: 82 / 77 fl

Expected completion: 2018

Designed by the acclaimed French architect Jean Nouvel, the MoMA Tower, which his studio named Tour Verre, successfully made its way through the review process of the City Planning Commission in the summer of 2009, although with a reduction of height from the original proposal for 1,250 ft., which was cut down to 1,050 ft. The project was halted, however, by the severe recession in financial markets that effectively ended all real estate lending. The project has since been revived, and construction began in 2015.

MoMA will be integrated into the tower: the third, fourth and fifth floors of the new building will serve as 40,000 sq. ft. of additional gallery space for the museum, and residences of the tower will receive benefactor memberships to the museum. Ultimately, the space will play an important part for the MoMA in reassessing the display of their collections in the building’s space.

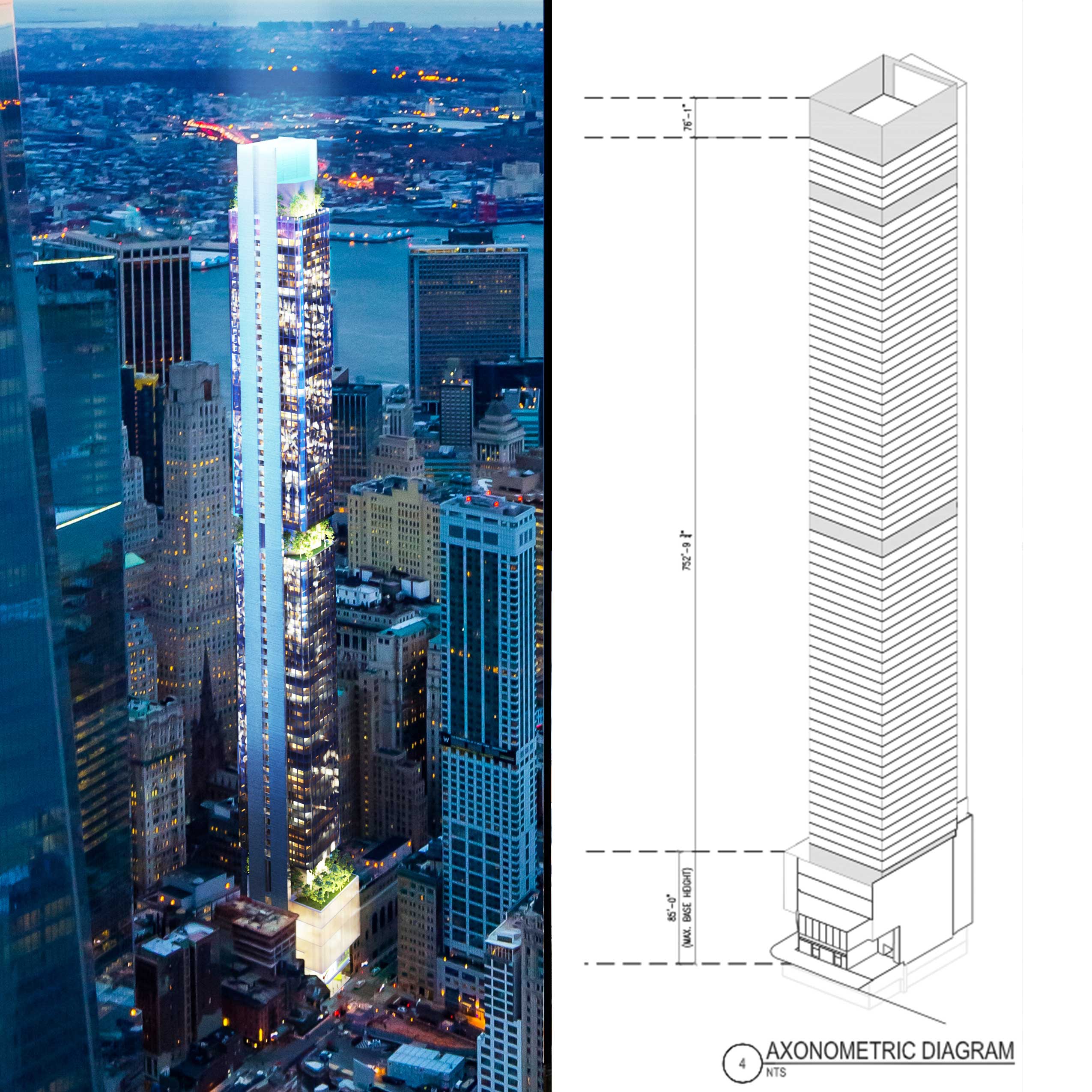

See MoMA Tower in SKY HIGH4. 9 DeKalb

Height to Tip: 1,066 ft / 325 m

Highest Occupied:

Stories / Levels: 73

Expected completion: 2019

Brooklyn’s first entry into the category of super-slenders, and its future tallest building, is another record-setting project by the same team of developer and architect, JDS and SHoP, responsible for the skinniest of all Manhattan towers, 111 W. 57th Street. At 1,066 feet, the building now known as 9 DeKalb, will dominate the in Downtown Brooklyn skyline. Unlike all the Manhattan towers, though, it will be a rental building that contains 500 rental units, of which 20 percent will be “affordable” due to the project’s 421-a tax exemption status.

JDS Development initiated the project in 2014 with the purchase of the five-story building at 340 Flatbush Avenue, then in December 2015 added the adjacent designated landmark Dime Savings Bank to create a large site and accumulate an additional 300,000 square feet of air rights. The triangular block is bounded by DeKalb Avenue, the Flatbush Avenue Extension, and Fleet Street and lies within the Special Downtown Brooklyn Zoning District, which was established in 2004 and which has spawned a wave of tall residential buildings. While this location permits the proposed tower to rise “as of right”, i.e., without city approval, because the project includes alterations to the landmarked bank, the project was reviewed, and passed, by the Landmarks Preservation Commission in April, 2016.

The hexagonal plan of the tower is based on of the geometries of the elaborate floor-tiles and ceiling coffers of the Dime Savings Bank, as well as the desire to protect views of the bank’s classical façade and domed roof from Flatbush Avenue Extension and the adjacent Albee Square. The tower’s base will contain over 100,000 square feet of retail and commercial space that will incorporate the bank’s fully-restored interior. A series of setbacks shape the tower into a faceted form that recalls Art Deco skyscrapers of the 1920s, and varied bronze mullions accentuate the verticals, culminating in a distinctive crown.

3. 432 Park Avenue

Height to Tip: 1,396 ft / 426 m

Highest Occupied: 1,287 ft / 392 m

Stories / Levels: 96 / 88

Completed: 2015

With a flat rooftop that squares off at 1,396 ft., 432 Park Avenue is — in the words of its developers Macklowe Properties and the CIM Group — the loftiest residence "in the Western Hemisphere." At that height, it will be taller than the 1,368-foot roof of One World Trade Center and the roof of original WTC Tower 1, which from 1971-1973 was the world's tallest building. However, two taller residential buildings will beat out 432 Park’s title upon their completion in 2018: 111 W 57th and the Central Park Tower.

Exemplifying “the logic of luxury,” the tower's soaring height is predicated on its compact 93 sq. ft. floor plate and extra-high ceilings, which produce its slenderness ratio of 1:15. Designed by Rafael Viñoly, the emphatic white grid of the concrete frame, divided into six sections by open mechanical floors, represents an integration of the elegant architectural concept and structural logic that sets 432 Park Avenue apart from its curtain-wall contemporaries.

See 432 Park Ave in SKY HIGH2. 111 West 57th Street

Height to Tip: 1,438 ft / 438 m

Highest Occupied: 1,134 ft / 346 m

Stories / Levels: 80

Expected completion: 2018

The feather-thin tower, projected to rise 1,438 ft., under construction at 111 W 57th St. is the most extreme example in New York to date of a design that uses a development strategy of slenderness. With a ratio of the width of the base to height of 1:23, it will be by far the most slender building in the world.

The stepped-back silhouette of tower, which uses textured terra-cotta ornament to disguise the concrete shear wall structure, shows the inventiveness of both the architects, SHoP, and the engineers, the WSP Group. According to the architects, “the façade is designed to read at multiple scales and vantage points; the shaping of the terra cotta creates a sweeping play of shadow and light from the city scale, as the texture of the terra cotta panels and inlaid bronze filigree provides richness up close.”

As for the building’s close proximity to the New York landmark Steinway Building, the building’s developers, JDS Development and Property Markets Group, have worked carefully with SHoP and the Landmarks Preservation Committee to maintain its presence in the neighborhood. According to SHoP, “the bulk of the new tower massing is set back from the street to maintain visibility to the three primary sides of the Steinway Building’s front tower,” and the design will “strategically intersect with the historic building to maintain the character and independence of the landmark.”

See 111 West 57th Street in SKY HIGH1. Central Park Tower

Left: Credit New York YIMBY.

Height to Tip: 1,569 ft / 478 m

Highest Occupied: 1,450 ft / 442 m

Stories / Levels: 99

Expected completion: 2019

Expected to be completed in 2019, Central Park Tower (previously know as the Nordstrom Tower) will be the tallest residential building in the Western Hemisphere. Designed by Adrian Smith + Gordon Gill Architecture – who, while working for architects Skidmore, Owingss & Merill, designed the world’s current tallest building, the 2,717-foot Burj Khalifa – the Central Park Tower is purported to have the highest roof in the nation at 1,569 ft.. Besides its near-200 residential units, the building will house a hotel and a 363,000 square-foot Nordstrom department store in its base. While construction on the tower has already begun, the developer, Extell, has vigorously denied that any drawings published to date represent the building’s final design.

The Central Park Tower will rise above the Art Students League, which currently occupies a landmarked building. Extell paid the League over $50 million in 2005 and 2006 in order to secure air rights.

*Stories - Floor count as described by developers

*Levels - Floor count as described by CTBUH Skyscraper Center Database

NEW YORK'S HISTORY OF SLENDERNESS

New York City is the birthplace of the improbably slender tower. In the late 19th- and early 20th century, many tall shafts rose over every square foot of their narrow, high-priced lots. Indeed, it was the high value of the land and the potential offered by the technology of the elevator and steel-cage construction to pile many floors of rentable space onto a small lot that made New York a city of towers.

There were three major stages and styles of slenderness in New York's high-rise history. The first was a period of skyrocketing growth when, until the passage of the city's first zoning law in 1916, no municipal regulations constrained height. By 1909, the Metropolitan Life Insurance Tower rose 700 feet-- 50 stories-- on a lot only 75 x 85 feet. Examples of these laissez-faire structures, spanning 1889-1916 are shown above.

Left: Cities Service Building, 1930s. Collection of the Skyscraper Museum

Right: Chrysler Building, 1930s. Collection of The Skycraper Museum

A second phase of vertical ambition and energy came in the 1920s. Shaped by the massing formula set by the 1916 zoning law, buildings with bulky pyramidal bases and slender soaring towers, covering no more than 25 percent of the lot area, became the new characteristic type of New York skyscrapers.

Because the 1916 zoning law applied to commercial buildings, including hotels, in the 1920s, the swank hotels that lined Fifth Avenue at the southeast corner of Central Park could sport tall and slender towers. The Pierre and Sherry Netherland illustrate both the enduring attraction of park views in the luxury life of New York that predict the new residential towers of the twenty-first century.

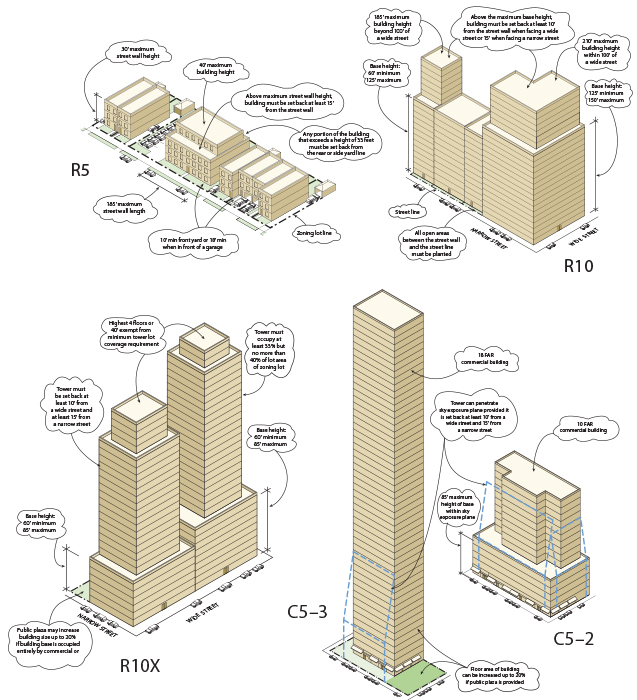

The diagrams shown here, compiled from the current zoning primer, available on line on the website of the NYC Department of City Planning, illustrate several formulas for residential zones.

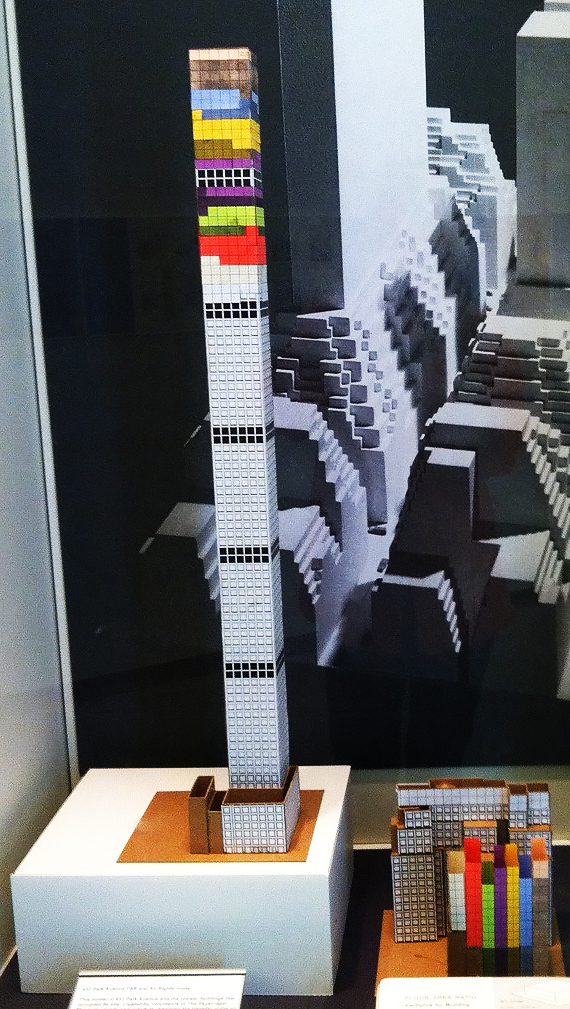

Installation shot of 432 Park air rights model.

After 1961, a new zoning law set a limit on building height -- or more accurately, imposed a maximum total floor area permitted on a given lot. It introduced a new formula, called the Floor Area Ratio (FAR). A developer can arrange the allowable FAR in any sort of massing, as some variations from the current zoning primer illustrate.

The 1961 law established the principle of “as-of-right,” which allows property owners to design and build whatever they wish without a public review process, so long as they follow zoning rules and do not exceed the maximum FAR allowed for that lot. It also created the concept of air rights, which said that if an existing building has not used all of the FAR allowed that lot, the unused “air rights” could be sold to the owner of an adjacent lot/s and used there. This mechanism, also known as “transferable development rights” (TDRs), lets developers join lots to increase the FAR that can be piled onto a single site. However, when the underbuilt area of a lot is sold and used on an adjacent site, that low-rise space will then remain open forever. FAR is finite: it can only be used once. TDRs are a cap-and-trade system.

All of the super-slender towers use this method of assembling lots and transferring air rights to consolidate and concentrate their collective FAR into one tall tower. Developers generally demolish the underbuilt structures to create a larger site for their project, even if the tower will cover only a portion. At 432 Park Avenue, for example, the mid-block tower is only 93 feet square and is set back 60 ft. from 56th Street and fronted by a plaza. A low-rise commercial building at the corner creates another zone of open space where the 22-story Drake Hotel once stood.

What are the Ten Tallest Topped-out Towers in the World Today?